| Home |

|

Alpheus

Minerd |

|

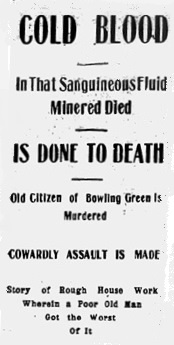

Alpheus' murder headline news |

Alpheus Minerd was born in 1845, about the time his family moved from New Rumley, Harrison County, OH to Tontogany, Wood County, OH. He was the son of Samuel and Susanna (Hueston) Minerd.

Alpheus was a Civil War soldier and prisoner of war. Later, his mental disabilities led the federal government to convene a grand jury to investigate charges of criminal fraud. As an older man, he was brutally murdered, a sad postscript to a life lived under the dark cloud of mental illness and physical suffering.

The focus of Alpheus' legal case was whether he became insane before or during the war. If his illness occurred during the war, he was entitled to a federal pension. Investigators took hundreds of pages of testimony from eyewitnesses to determine whether Alpheus’ family, knowing that he was mentally ill before the war, lied to the government to try to obtain the pension.

The cold-blooded murder of Alpheus by a mulatto man had racial overtones. It "landed on page 1 of every newspaper in the state and brought everlasting fame -- of a sort" to Hardin County, OH, the place where the crime occurred. The killer, William Nichols, had "the distinction of having been one of the first prisoners executed in the electric chair at the Ohio state penitentiary" in Columbus. In fact, he and his murderer are mentioned in the January-February 2004 issue of Timeline Magazine of the Ohio Historical Society, in a cover feature about the penitentiary.

Most of Alpheus' story is culled from the extensive file of his pension papers, now in the National Archives in Washington, DC. Part of his tale is told in the newspapers of the day, and also in the 1940 book, A Complete History of The Scioto Marsh by Carl Drumm, republished in 1976 by the Hardin County Historical Society.

Unfortunately, no photographs of Alpheus are known.

Schoolboy Days and Early Adulthood

|

| Book naming Alpheus |

As a small child, Alpheus suffered from the measles but otherwise lived the active vigorous life of a farmer boy.

Growing into a young man, Alpheus was considered sound and healthy, though with mental “peculiarities,” but not “crazy” or insane. Despite conflicting testimonies from family, friends and neighbors, he was considered “peculiar … dull … obstinate … [and] morose” but also “sound, bright and healthy in mind and body as anyone in the community…”

Many friends said Alpheus “was of sound mind …” Schoolmate Ephraim Wires thought Alpheus “was recognized as one of the brightest boys in the school so far as learning was concerned.” Wenmon Wade, who taught Alpheus in 1861 and 1862, said that “Alpheus Minerd was of sound and normal mind, and was not insane, nor cranky, and he was an ordinarially apt scholar.”

Brother in law William L. Jewell said that before the war, Alpheus “did full work, was clearheaded, bright and intelligent, free from any eccentricities, lively in manner, not at all morose nor sullen, free from head-aches and disease of every kind.”

Said boyhood friend James Jeffers, “I always considered him sane and of sound mind – only a little mischevious.” And Sarah McCombs, who went to dances and parties with Alpheus, said he “was always considered by all of the young people of our acquaintance as bright, intelegent, and witty, as any. He was always very particular in his dress, and always shown good taste in his dress.”

But Alpheus had many enemies. Perhaps the most savage critique of Alpheus came from neighbor Emma Stone, a housewife. She claimed to have lived a half-mile from the Minerds, and known Alpheus before his enlistment. Stone said that he:

… was certainly of unsound mind, was out of his head, was deranged. All that time, he was moody, very high & ugly tempered, destructive, vicious, unsociable, unboyish, not like other boys, morose most of the time, uncompanionable, queer in his ways. He kept his head down, would not look one in the face, was very troublesome in school, was violent in temper…. He was beyond question insane or deranged…. [He] is a bad man, of infamous reputation, a trickster.

Neighbor Jacob Vollmar testified that Alpheus was “inclined to be alone” and “wanted to destroy and break things, all the time.” Neighbor Nancy McMann recalled that “He would and did skulk away by himself when company came to his home” and said he “had a bad looking countenance, a hang-dog look… He had a terrible and ‘desperate’ temper. His temper ran away with him. It controlled him.” Catharine Addmon, who resided on an adjoining farm, and who “knew the Minerd family well,” once recalled that “when at his parent’s house, … [Alpheus] was up stairs, fastened up there for extreme ugliness.”

Alpheus allegedly once took a club and “went at the school teacher Elizabeth Reams, to drive her out of the room,” said neighbor Thomas Stone, in whose home the teacher boarded. “He had no cause for his actions.” Stone mason William G.W. Black, who lived a half-mile from the Minerds, said that Alpheus “flew into a rage at no seeming provocation. He always sought to destroy whatever came in his way. He caused his father and mother continual trouble. His father had to whip him often.”

Even his brother Jacob admitted that Alpheus “was moody, of very high temper.”

David V. Gundy, who grew up on an adjacent farm, recalled that Alpheus “seemed to take delight in destroying things and injuring and abusing animals.” Neighbor Hiram Cunning said that as a young man, Alpheus “often ran away from home and remained away some time…” Several friends recalled that he earned the nickname “Queer Alph” or “Fool Alph.”

Grueling Civil War Service

As a teenager, Alpheus stood 5 feet 5 inches tall, with dark hair and hazel eyes. On Dec. 22, 1863, he and future brother in law William H. Shepard both enlisted in Company D of the 34th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Shepard later testified that during their time in the Army, he was with Alpheus “all the time …"

The two men saw action in 24 battles during a 6-month period in 1864, including the following:

Princeton, WV (May 6), Cloyds Mountain, VA (May 9-10), Panther Gap, WV (June 3), Piedmont, VA (June 5), Buffalo Gap, WV (June 6), Lexington, WV (June 10), Buckhannon, WV (June 14), Otter Creek, VA (June 16), Lynchburg, WV (June 17), Liberty, WV (June 20), Salem, VA (June 21), Monocacy, MD (July 9), Snickers Gap (July 17), Third Winchester, VA (July 20-24), Kernstown, VA (July 23), Summit Point, VA (Aug. 21), Halltown, VA (Aug. 24, 26-27), Berryville, VA (Sept. 3-4), Martinsburg, WV (Sept. 18), Opequon, VA (Sept. 19), Fishers Hill, VA (Sept. 22) and Cedar Creek, VA (Oct. 19).

|

Action at the Battle of Winchester, VA in September 1864 |

|

|

Red-brick Pemberton |

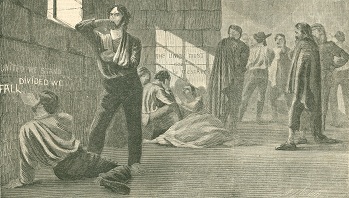

Just after the new year began in 1865, on Jan. 11, the 34th Ohio fought at Beverly, WV. Alpheus and Shepard were captured, and sent to Pemberton Prison in Richmond, VA. For more than a month, they were incarcerated together. Seen here, the red-brick Pemberton was a converted warehouse, along the James River, and beside Libby Prison, a notoriously filthy and deadly facility, considered one of the Confederacy's worst.

One Libby prisoner complained of having to sleep on bare floors, in front of open windows, with insufficient clothes or blankets. The men also were exposed to cold temperatures, dampness and germ-carrying insects from the nearby, slow-flowing river. Sanitation was non-existent -- prisoners relieved their bladders and bowels in the corners of their rooms.

Writing later about the experience of being POWs together, William said that Alpheus:

… seemed to take his imprisonment very much to heart, his great fear seemed to be that he would starve and die in prison. He got very homesick, and brooded over and almost continually talked about the worry of being in prison, and starving to death, and within a month or six weeks after his capture he began to show signs of mental derangement, became moody and sullen, where as before [he] had been lively and cheerful… He got dumpish & finally fell sick and became delirious before he was taken to the hospital.

On Feb. 17, 1865, Alpheus was exchanged at Aikens Landing, VA and was sent to Camp Parole, MD. From there, he went to Camp Chase, OH, where on Feb. 28 he was transferred to Co. D of the 36th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. That day, he also received a furlough lasting one month. He immediately went to his parents’ home near Tontogany for a much-needed rest.

|

|

|

Civil War POWs in a Confederate prison in Richmond |

|

|

|

Solitary water hydrant

available |

After he returned home, brother in law Jewell observed that Alpheus “looked a little thin & somewhat the worse for wear, but he was in fair physician condition. He was then silent most of the time, not inclined to talk, seemed to be downhearted & inclined to separate himself from others. [Yet] some of the time he was bright and cheerful and talkative.”

After their furlough, Alpheus and Shepard returned to the Army, but were separated when Alpheus was sent to his new regiment on April 6, stationed at Camp Chase. The war ended at about that time, and he saw no further armed conflict.

Discharged in July 1865, he went back to his parents’ home, and lived there until about October of that year.

Brother Jacob Minerd, recalling this period, said “…it was then that I first noticed anything wrong with his mind -- (That was on the first day after his return home from the army.)”

Postwar Behavior Turns Ugly

After his return him, Alpheus’ behavior declined steadily. Neighbor David V. Gundy thought he had “grown older and uglier.” Another neighbor, Samuel Duke, said sharply that Alpheus “seemed to be an overbearing disposition. It is the nature of the whole family.”

Through painful experience, brother in law Jewell learned that Alpheus’ work habits and behavior had deteriorated. He said that in October 1865, Alpheus “began to work for me. He worked for me four days, then went home; returned after two weeks, worked for me two days, then went home again.”

Alpheus had sent money home to his father during the war. But in late 1865, when he asked for it back, his father refused, for reasons unknown. Becoming furious, said an observer, Alpheus “always after that … had a grudge against his father and tried to injure him. He is supposed to have cut his father’s [new] harness to pieces in the winter of 1865 and 1866.”

Mother Susan, who was intimidated by her son's irrational behavior, related that he did no productive work, but rather:

… staid around the house with me the most of the time. He would tell me things that he said occurred while he was in the Army, and upon my relating the circumstances to the family he would insist that he never said so, that if I said so I was a liar and the truth was not in me. He would get angry if I insisted he did say so and so. Soon after he came home he began suddenly leaving home, without any apparent aim or purpose; he would be gone for days in the neighborhood, would give no account of himself, as to where he had been or why he went away – would get angry and impatient when asked about it.

Said his father, “One morning I found him in an apple tree. He had been out all night…. At home he would take tea spoons and such things and bury them, we had to watch him all the time. He would get angry and threaten our lives.”

Alpheus later returned to the Jewell home and agreed to labor again for his brother in law. But the arrangement, as before, did not work, Jewell said:

I discharged him for abusing my horses. He again worked for me from Oct. 1, 1866 to the middle or last of Nov. 1866. In Oct. 1866, he disobeyed my orders in regard to work, got angry, came at me with a pitch-fork, and I seized & threw him and choked him unto submission, I never had any trouble with him afterward. The last of Nov. 1866, he went home, and never again worked for me.

Sister Pera Jewell commented that he “was destructive and seemed to desire to kill & destroy. He killed my chickens & was cruel to the horses. He had a horse of his own but he was kind to that.”

After returning to his parents’ home in November 1866, Alpheus hired out as a laborer from time to time. Then, shortly afterward, he left home, taking about $500 with him, all that he could gather. Recalled his mother:

When he went he seemed to have no place in view to go to, nor business to go into, but just had an insane notion of going somewhere. He was gone about a year. When he came back he had spent all that he had, and was ragged. He would give no account of where he had been, what he had been doing, or what he had done with his money.

In late 1868, Alpheus left home again, and wondered up into Minnesota. He did not return until March of 1869 (or 1870). During that period, he did not write to or contact his family in any way.

Moving back in with his parents after his time in Minnesota, Alpheus “was a great deal worse than when he went away, grew continually worse, and finally violent and dangerous,” Jewell recalled. “He seemed to have a grudge against his father.” Sister Pera said “he got dangerous & threatened to kill my father…”

Into the Insane Asylum

|

|

|

Columbus Hospital for the Insane |

Standing the abuse no longer, father Samuel sought court protection against his son. Alpheus was declared insane by the Wood County Orphans Court in a decision handed down in 1871. He was sent to an insane asylum in Newburg (Cleveland), OH. He escaped from Newburg on a number of occasions, and Tontogany grocer William Crom once said he had “assisted in retaking him to the asylum on four or five different occasions when he has made his escape…” When Alpheus was captured again in 1877 after an escape, his family successfully applied for him to be admitted to the Columbus Hospital for the Insane.

Alpheus later was transferred to mental health facilities in Toledo and Columbus, OH, remaining institutionalized off and on for a total of 17-plus years.

On Oct. 19, 1881, the Orphans Court appointed Alpheus’ brother in law William Jewell as his legal guardian. He escaped from the Columbus Asylum for the Insane in the late summer of 1883. William J. Smith was paid $23.20 by the state of Ohio for returning Alpheus to the institution, a fact reported in Annual Reports for 1883, Part II, of the General Assembly of Ohio.

Alpheus was released at the end of 1888, and returned to Bowling Green, where he moved back in with the Jewells. By 1890, he had lost much of his anger. Recalled sister Jemima Burditt, “He has been out of his head and insane, but not dangerous.”

|

|

|

Bowling Green depot, CH&D Railroad |

In December 1900, Alpheus slipped away and went to Green Spring, OH. Jewell went looking for him, and spent two days at Green Spring. He found Alpheus, bought him several meals and apparently took him home. They no doubt arrived in back in Bowling Green via the railroad -- seen here is a rare old photographic postcard of the Bowling Green depot of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton (CH&D) Railroad.

Controversy Over a Civil War Pension

In February 1882, Jewell filed a claim to receive a federal pension for Alpheus’ disabilities as a POW. It took more than 8 years for the government to reach a conclusion.

As part of the process of interviewing witnesses, the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Ohio learned of a possible crime involved with the matter. It began to investigate an allegation that Jewell, along with Alpheus' father and brother Jacob, had conspired to defraud the government by lying that Alpheus had been normal before the war. A grand jury was convened in December 1889, but apparently decided there was no grounds for a trial. Wrote Assistant District Attorney E.S. Cook, “The testimony before the grand jury certainly developed the fact that this man was sound and healthy, though with mental peculiarities, prior to his enlistment.”

The government rejected Jewell’s pension claim in March 1890. The Jewells were furious, and asked for reconsideration. They hired Washington DC plaintiffs’ lawyer George E. Lemon, nationally known as a Civil War pension expert. (Lemon served as pension lawyer for many of our Minerd-Miner-Minor cousins.)

The Jewells then procured many favorable eyewitness testimonies from Alpheus’ childhood friends, longtime neighbors and members of his Civil War regiment. They included Francis Franklin, Jacob C. Jeffers, Mary Jane Jeffers, Louisa Jeffers, John Soash, Hiram Cunning, Nancy McMann, Edward M. Foster, Ephraim Wires, Peter H. Van Valkenberg, James Jeffers, Greenberry Burditt, Wenmon Wade, David Murdock, William H. Shepard, Sarah Jane Patterson, Elizabeth Treadwell, Luis Godfred, William Crom, Samuel W. Whitmore, Alburtis Russell, Luther Black, David Mitchell, David McCombs, George W. Rickard, A.J. Rickard and Sarah A. Streeter.

By April 1890, James M. Wells, a special examiner for the Commissioner of Pensions, had again investigated the case, and recommended that the pension application again be rejected.

Wells took further testimony in June 1890, but was greatly dismayed at what he heard. He accused Jewell of having “drummed up testimony of questionable character to such an extent that his bare-faced and determined attempt to secure a fraudulent pension has led some of the most reputable citizens of Wood Co., O., to request me to take further testimony in the case. I have done so, and I submit herewith the testimony of four men of high character and unquestionable reputation for truth.”

Wells interviewed lawyer Edwin Fuller, justice of the peace and former probate judge of the county. Fuller knew the Minerds, and had officiated at the weddings of two of Alpheus’ sisters in the family home. In their discussions, Fuller told Wells that “the testimony as given … since the rejection of the claim … constituted some of the most reckless swearing he had ever heard.” Wells came to the conclusion that Alpheus' family had "evidently combined to work through this fraudulent claim. I … recommend … the prosecution of William L. Jewell as principal and William J. Burditt and the father of the soldier as [criminal participants].”

The family filed an appeal in February 1891, and it was accepted two months later, with the news reported throughout Ohio, including in the Cleveland Leader and Herald. However, the matter was overturned in April 1892 by the Department of the Interior.

Again greatly dismayed, the Jewells pressed their case. They asked their lawyer, George Lemon, to see that someone other than Wells be assigned to the case. “We have no use for him,” Jewell wrote. The lawyer filed a motion for reconsideration in January 1893. He cited inconsistencies in the government’s position. Praising Alpheus’ extensive battle record during 1864-1865, Lemon also asked the government a rhetorical question:

Could any man mentally diseased endure the confusion and excitement of the numerous battles in which Minerd was a participant without his trouble becoming manifest to his associates? No! It would have been impossible for a man with a weak intellect to have endured the horrors of the amount of actual warfare that Minerd was engaged in without exhibiting to his comrades any signs or symptoms of a diseased mind.

Unfortunately for the Jewells, their motion was overruled in March 1894. However, for reasons that are not clear, Alpheus did receive some level of pension at the time of his grisly murder in 1903.

|

Alpheus' killer pictured in prison |

A Cold-Blooded Murder

By the turn of the 20th century, Alpheus lived a life of a full-time vagabond, keeping company with William Nichols (1836-1904).

In 1901, he left the Jewell residence for the last time. He made his home in the northwest corner of the Scioto Marsh in Hardin County. The booklet, The Palace of Death, describes his dwelling as a:

miserable old shack ... which served in some degree to shelter him from the winter blasts and from the summer heat. Here for many years he lived alone, leading a quiet, industrious and happy life, enjoying the confidence and respect of his neighbors; and when William Nichols, hungry, footsore and weary applied at his cabin door for food and shelter, the old soldier generously took his comrade in. The companionship proved to be congenial, and they agreed to live together.

Nichols, seen here, was of mixed race origins from Carmel, Highland County, OH, whose reputation was unsavory. The Bowling Green Daily Sentinel said that in Carmel, Nichols had led a "colony of half-breed negroes [who] maintained a starving existence by petty stealing for the past twenty-five years."

Alpheus and Nichols spent most of their time in Kenton, Hardin County, known for its lush flat fields of black earth, perfect for onion farming. They often picked roots and sold them at local markets. While in the Kenton area, they "drank considerably" amid the "highland hills," said the Daily Sentinel. It was there, near the town of McGuffey, that Alpheus met his bloody end.

According to the Complete History of the Scioto Marsh, the two men played "seven-up games at ten dollars a game," with Nichols frequently winning.

About two miles out of McGuffey, at the edge of the Shadley Woods, the two men stopped to rest. Both were drunk. A card game was started, and when Nichols won Minerd's gold watch, a fight ensued. When it was over, Minerd lay dead on the ground, stabbed and shot.

|

|

|

Copse of trees where

Alpheus' |

The next day, July 29, 1903, Alpheus' "dead and mutilated body" was discovered in a stand of trees. The approximate site of where the corpse was found is seen here circa 2002, along a tree line near a steep drainage ditch.

Nichols was immediately sought as a material witness. Law enforcement officials learned that he had left the area, and had purchased a horse and buggy just before going. A sheriff tracked "his trail through Delaware to Washington Court House, then to Greenfield and from there to the hamlet of Carmel…" Nichols was lured into a public store and arrested there, where Alpheus’ pocket watch was found in his possession. The suspect tried to explain it by saying the victim, fearing the watch would be stolen, gave it to Nichols for safekeeping.

The sheriff took Nichols back to Hardin County by train. During a stopover in Belle Center, Logan County, they barely escaped a mob, which "had gathered at the railway station and threatened to take the prisoner away … and lynch him, but the train pulled out before the mob could accomplish its threatened purpose." News of the search was printed in such faraway newspapers as the San Francisco Call, New-York Tribune, Walla Walla Evening Statesman in Washington State and the Little Falls Herald in Minnesota.

|

Continuing sensational news coverage |

The Jewells learned of the murder by reading it in the newspaper. Said the Daily Sentinel, "They at once went to Kenton and asked the privilege of bringing the [body home] for burial, but this was denied them because of the condition of the body."

The final resting place of Alpheus is unknown but is being researched. The Veterans Administration in Washington, DC has no record of his burial.

A Date with the Electric Chair

|

|

|

Hardin County Courthouse |

Though he vigorously denied responsibility for the killing, Nichols was held in Kenton for trial. The proceedings took place in the Hardin County Courthouse, seen here.

"For a time the crime bid fair to be a murder mystery," reported the Hardin County Republican, "but the officers [who] went on the track of Nichols, rounded up such an array of evidence that he was convicted and sentenced to be electrocuted..."

|

Headlines as the execution date nears |

The decision was handed down on Saturday, Nov. 7, 1903. Much as they likely would today, newspaper headlines all across the state of Ohio blared the sensational news that Nichols was guilty of first degree murder. The news stories trumpeted the fact that he would be executed for his grisly crime. Nichols' date with the electric chair, known grimly as 'Old Sparky,' was set for Feb. 10, 1904. The death watch was on.

Nichols was sent from Kenton to Columbus, on the T&O Railroad, to serve out his final months. As he stood at the depot, with a crowd of nearly 300 onlookers, he "seemed not in the least moved and joked and talked with those about him as he had in the past," said the Hardin County Republican.

He was incarcerated at the Ohio Penitentiary for a little over a year, as he appealed his case. Just 10 days before he was to die, the federal district court granted him a temporary stay of execution, pending certain appeals. The Hardin County Republican reported that "Nichols had grown more worried and nervous day by day, and as the number of hours steadily decreased, his fears almost made him hysterical."

|

|

|

Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus |

|

Headlines of Nichols' violence |

In May, with his execution still pending, Nichols had a most unexpected visitor -- a long lost daughter, Mamie Cousins, of Toledo. The Republican said she had not seen her father for about a quarter century. When they first saw each other in the penitentiary, Mamie was:

...all a tremble with anticipation and fear, but "Bill" just put out a brawny hand and laughed. Immediately it was all gone, all the fearful horror of this meeting in the shadow of death as it were, for the electric chair, draped and grim, was only around the corner of the annex inclosure. The little woman's face cleared like an April day and she laughed in unison... "Never mind, honey, honey," [he said] and he smoothed her hair caressingly, "maybe it won't be so bad, after all. They hain't got your daddy scared yet. The courts hain't said finally that I am to go.

The meeting provided an opportunity for Nichols to win extensive, sympathetic publicity in statewide newspapers.

|

Ohio Penitentiary

electric chair, |

After Mamie's visit, "it was then agreed to get all the members of the family [together] for a last reunion." In addition to Mamie, members of the family who agreed to the visit were Nichols' wife Nancy and their children Tommie and Annie of Wilmington, OH; Mollie of St. Louis; and Frank of southern Ohio.

In June 1904, Nichols awakened one midnight to a mysterious voice, one he called "deep and terrible." The voice allegedly chanted, "Murder and thief, thy doom is sealed." He "shrank back in his cell, hair on end and face pallid," according to a wire story that ran in Ohio newspapers. "Your death is decreed,' droned the voice. 'I am the ghost of Alfred Minard, the old soldier you murdered, near Kenton'." Alfred reported the incident to his jailers, and later it came out that another condemned inmate, Dutch Fisher, was a ventroloquist who pulled the prank for fun.

...finally knocked Nichols down and held him until the guards had secured the weapon and had Nichols secure. He was rushed into solitary confinement. In his absence his cell was searched, and two formidable pieces of iron, both sharpened at each end, were found. Nichols was strung up [by the wrists] and made Rome howl for a time, but he finally weakened and said he would behave himself.

|

Fornshall's

history of |

The violent attack generated negative news articles once again, perhaps revealing his true dark side, apparently now for all to see. On Oct. 10, 1904, his case was reconsidered by the circuit court in Kenton, and his conviction was confirmed.

Less than two months later, on Dec. 9, 1904, Nichols' options and delays ran out. At the stroke of midnight, he was put to death via electrocution, one of the first Ohioans to die that way in the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus, and only the 22nd Ohio prisoner overall to die in an electric chair in the state. The room and chair where he died are seen here in a rare old color-tinted postcard.

Reported the Perrysburg Journal, "Despite his efforts to enlist the sympathy of his former friends to keep his body from reaching the dissecting table, Nichols failed." His burial place is unknown.

News of his execution reached newspapers coast to coast, among them the Salt Lake Tribune in Utah and San Francisco Call in California.

|

Book naming Alpheus |

An even more sensationalistic account of the murder was included in a chapter of H.M. Fogle's 1908 book, The Palace of Death or The Ohio Penitentiary Annex. It claimed that Nichols was the "oldest man ever confined in the Annex death-chamber, and was an object of much pity. His hair and moustache were white with the frosts of many winters." The chapter on Nichols closed with this flowery description of the aftermath of the electrocution:

Then bid we all adieu to the mortal elements of him who fills a felon's grave, leaving only to memory and the record page the preservation of his unnatural crime. The judgement belongs to God.

Alpheus and his brothers-in-law William J. Burditt and William H. Shepard are mentioned in a lavishly illustrated, 2011 book about about one of their cousins who also was a veteran of the Civil War -- entitled Well At This Time: the Civil War Diaries and Army Convalescence Saga of Farmboy Ephraim Miner.

The book, authored by the founder of this website, is seen at left. [More]

Copyright © 2002-2004, 2007, 2014, 2019 Mark A. Miner