|

Isaac

Van Horn |

|

| Isaac Van Horn |

Isaac Van Horn was born on Dec. 7, 1830 either on Laurel Hill, Fayette County, PA or near Scio, Harrison County, OH, the son of Samuel and Sophia (Minard) Van Horn.

As a soldier in the Civil War, he was captured and suffered terribly as a prisoner of war in Confederate prisons for many months. He also is profiled in Beers' 1897 book, Commemorative Historical and Biographical Record of Wood County, Ohio.

The reason his birthplace is uncertain is that Isaac himself named both sites on separate occasions. Though his parents were longtime residents of Ohio, long before he was born, the fact that Isaac's birthplace is not precisely known suggests that the family was frequently on the move between Ohio and Pennsylvania in the 1820s and '30s. It also implies that Isaac's mother continued to have ties to her many uncles, aunts and cousins in Fayette County, PA. In fact, when Isaac died in 1922, his daughter provided information for the death certificate, and gave the maiden name of Isaac's mother as 'Mienert.'

|

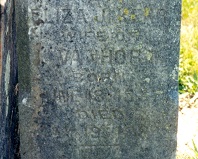

The infants' grave marker |

As a one-year-old, Isaac moved again with his parents to Wood County, OH, where the family settled for good. In his young adult years, he stood 5 feet 9 inches tall, and weighed about 165 lbs. He had blue eyes and dark hair, and worked on his parents' farm until he was age 25. Then, he purchased a farm of about 20 acres.

On Nov. 22, 1855, Isaac married neighbor Eliza J. Kerr (1837-1884), the daughter of farmer Jesse Kerr [also known as William B. Kerr] of Weston Township, Wood County. They resided in Weston and had four known children, two born before the war (Ella June Wolcott in 1858 and Etta May Van Horn in 1864) and one born afterward (Frank Wallace Van Horn in 1866).

Sadness gripped the family when baby daughter Etta died at the tender age of two months, on July 30, 1864, while Isaac was away at war. An unnamed baby son died at the age of six days in on May 19, 1872.

Little is known about Eliza, though her friend Harriet Williams later recalled that "We were pioneers, the Indians had not all left when we were children." One of her cousins, William L. Ross, testified on Isaac's behalf later in life, and wrote: "We are members of the great clan known as 'The Barton Cousins', I by birth, [Isaac] by marriage; and the history of each is known to the others." Eliza's sister, Mary M. Heeter, also provided testimony for Isaac when older.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, Isaac and his father and brothers Andrew and Eli are known to have signed a resolution in the formation of a Union League in Weston Township. "The primary object of this League," said the Perrysburg Journal, "is to unite all loyal men, without regard to past party predilections or differences, in an unconditional and unfaltering support of the Government, in all its efforts to crush the present wicked and causeless rebellion. And we do hereby pledge to the country, in this hour of peril, that we will spare no endeavor, as far as in us lies, to maintain unimpaired the National Unity, both in principle and territorial boundary."

|

| Isaac's profile in a county history |

Isaac enlisted in the Army for a period of 100 days. He was a member of Company C of the 144th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Ohio National Guard). His brother Austin also served during the war, in the 86th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

While on duty on Aug. 13, 1864 at Berryville, VA, Isaac was captured by the enemy. The regiment's acting second lieutenant, George Kimberlin, later said: "Vanhorn was taken prisoner by Moseby, while he with others were guarding a train, ... were taken early in the morning while at breakfast…"

Isaac was a prisoner for eight months at Belle Island, VA, Salisbury, SC and Libby (Richmond, VA), some of the most notorious and deadly of the Confederacy's prisons. One prisoner, a surgeon with the 12th West Virginia Infantry, complained of having to sleep on bare floors, in front of open windows, with insufficient clothes or blankets.

|

|

|

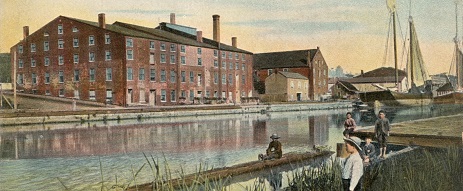

Red-brick Libby Prison, a converted warehouse, next to the sewer-like river |

|

| Deceptively peaceful image of

POWs killing time at Libby |

The men also were exposed to cold temperatures, dampness and germ-carrying insects from the nearby slow-moving James River. Sanitation was non-existent -- prisoners relieved their bladders and bowels in the corners of their rooms.

During the first month or so of Isaac's imprisonment, he suffered from sunstroke, a problem which would plague him the rest of his life. He also became deaf in one ear and caught scurvy, which "affected [my] eyes and teeth and hearing and debilitated [my] whole system," he said later.

Apparently, during his incarceration, he witnessed the death of a friend named McClain, a tragedy which would haunt him for years. The Commemorative Record said of Isaac that "He was the only one of seven, taken from his county, to survive prison life."

Isaac was exchanged at Coxes Wharf, VA and reported to Camp Parole, MD. He then was sent to Camp Chase, OH on March 15, 1865. He was treated for several days at Todd's Barracks in Columbus, and then was discharged on March 23, 1865. He went immediately to the home of Rev. Wallace in Pickaway, OH. He arrived after dark and was offered a bed to sleep in, but he declined, saying he "might have insects on him which would prove troublesome…"

The next morning Isaac came to breakfast, and ate heartily, and continued eating well after everyone else was done. Wallace then took Isaac by buggy to the train station, but Isaac declined to board the train for home, saying he wanted to remain with the Wallaces. Knowing Isaac was "not in his right mind," Wallace wrote a note for the train conductor to carry to the station agent at Isaac's home depot, saying that once he arrived there, Isaac should be detained until his family could come. Wallace and others then "forced … Vanhorn into the cars …" After arriving in Weston and being sedated, Isaac stayed the night at the house of friends, and the next morning his wife and father in law came to bring him to his parents' home.

Dr. J.B. Alford was called to treat Isaac, and found him unconscious "for about two days and delirious for several more days and not sane for several weeks…" Father in law Jesse Kerr said that upon arriving home, Isaac "was nothing but skin and bones."

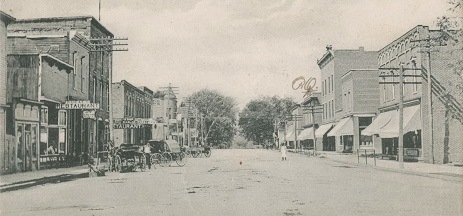

Isaac stayed at his parents' for about 6 weeks, until he felt well enough to go to his own home. His parents lived about two miles south of Grand Rapids, OH, while Isaac's residence was a half-mile west of the United Presbyterian Church in Weston Township.

|

|

Rare old postcard of Grand Rapids' Front Street |

|

| Isaac in later years |

After the war, Isaac resided in the Grand Rapids area, earning living as a carpenter and joiner, and as a laborer during harvests and "raising a corn crop…"

Neighbor Philip H. Heymann often saw him "cradling in the harvest field, mowing and all kinds of farming work…" He labored for John Walters in 1866 "at building a barn and worked in the sun in June of that year roofing said barn," Walters said later. "He never missed a day's work on account of sickness and was one of the most hearty eaters of any of the men employed by [me] that summer." He also worked as a carpenter with and for neighbor John Kimberlin, and in the summer of 1872 was hired by Dr. Andrew J. Gardner to "mend a church roof."

The Commemorative Record said he later purchased a 55-acre farm near Grand Rapids: "The improvements he has made thereon are of a high class, and he conducts the property in a model manner, having constructed ditches, planted orchards, and built substantial structures as needed."

Politically, said the Commemorative Record, he:

...cast his first vote for the Whig party. The issues of the war made him a "Black Republican" and he has adhered to that party since. He takes no active part in political work, and has never held an office, or been a juror, or been engaged in any legal controversy. By his friends and neighbors he is held in high esteem...

As the years progressed, Isaac did not like to talk about the war. But when asked specific questions about being in prison, he "readily answers all questions about it and seems to recollect acutely his sufferings while in the rebel prisons and the death of his friend McLain..."

|

| Book profiling Isaac |

Isaac suffered constantly from his war injuries, claiming he'd have attacks of vertigo and hear "roaring sounds in the head…" To keep his "sunstruck" head cool while working in the heat of the mid-day sun, he wore a wet cloth or a wet sponge in his hat.

By 1874, he was receiving a federal pension for his service in the amount of $12 a month. In 1897, his pension was $14 a month. A surgeon who examined Isaac in 1875 reported that he had "Pain on the top of the head almost constantly. Incoherent and forgetful. Talks in low and very slow manner. Evident subacute meningitis as evinced by constant pain, also softening of the brain shown by dementia…"

After Isaac began receiving his a pension, charges were made that he was not disabled enough to deserve a pension, and that he was a "malingerer." L. Holtzlander, a special government agent, investigated Isaac's case in 1878. Holtzlander interviewed the Van Horns and their neighbors. After taking many depositions, he concluded that "the pensioner feigns dementia when he goes before an examining surgeon."

When he went to the Van Horn home, fearing that Isaac would put on an act for him, Holtzlander pretended to want to buy potatoes. Said Holtzlander:

When I first addressed him, asking his name, the price of potatoes, how he would sell his &c, in my ordinary tone of voice he heard readily and answered my questions promptly but as soon as I made my real business known he walked stiffly and when I commenced to question him, he appeared very deaf, put his hand to ear to enable him to hear and then could hardly comprehend my questions, although, for a while, I spoke to him quite loudly. He also then assumed a stolid stare to carry the impression that he was demented and could not recollect past events… His wife was ready to answer for him and to tell how much he suffered and what a time she would have with that night… She always goes with him to the examining surgeon … to effect the same impression she attempted to make upon me. I had to advise her that I did not want any but the pensioner's own answers… [He] looks stout and hardy for a man of his age and his hands showed that he had worked hard.

|

|

|

Graves of Isaac and and his second wife Elizabeth at Beaver Creek Cemetery |

|

Eliza's fading grave marker |

Neighbor John Walters, who had known Isaac for years, gave testimony in the case in 1878. He said that Isaac was "just as sharp in a bargain and as able to attend to business matters as he ever was…"

The outcome of the case is not known, but Isaac apparently continued receiving some sort of pension from the government.

Sadly, Eliza passed away near Grand Rapids on May 19, 1884, at the age of 47. The cause of her death is not known. She was buried at Beaver Creek Cemetery, beside her infant children Ella and the unnamed son. Her name and dates were carved into the same tall upright stone that marked her children's final resting places. When photographed in the summer of 2002, the lettering was fading, but still faintly legible.

On Sept. 11, 1889, at Napoleon, Henry County, OH, Isaac married Elizabeth "Libbey" or "Lizzie" (Dean) Barton (1844-1923). Justice of the peace W.A. Tressler officiated. News of the marriage was announced in the Napoleon (OH) Democratic Northwest.

Elizabeth was a native of Riley Township, Sandusky County, OH, and had been married and divorced once before, to Civil War soldier Henry J. Barton. Elizabeth had a daughter from the first marriage, Ella Lowmaster.

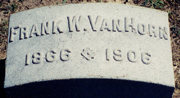

In 1906, Isaac endured the death of his 40-year-old son, Frank W. Van Horn, who had been stricken with heart valve disease.

Isaac suffered a stroke in 1920 or '21. Then, on about Feb. 28, 1922, he was stricken in an accident, when his clothes caught on fire, burning his legs terribly. He passed away a little over a week later, on March 8, 1922. He was buried in Beaver Creek Cemetery in Grand Rapids Township, Wood County. The local newspaper "announced the death and gave a short biographical history," said his undertaker, K.H. Kyper.

Circa 1922, widow Elizabeth claimed that she was "very old and feeble" and needed "assistance in dressing and undressing." She lived only a year longer than her husband, and died on Sept. 27, 1923, at the age of 79.

~ Son Frank W. Van Horn ~

|

| Beaver Creek Cemetery |

Son Frank W. Van Horn (1866-1906) was born in 1866.

Circa 1891, when he would have been about 24 years of age, Frank entered into marriage with 24-year-old Nora L. (Dec. 1866- ? ).

The couple dwelled in Grand Rapids, Wood County.

When the federal census enumeration was made in 1900, the couple had not yet reproduced. At that time, Frank labored as a farmer. Living under their roof in 1900 were eight-year-old Rose E. Rochte and 36-year-old William Kerstetter.

Sadly, Frank was burdened with heart valve disease. On June 29, 1906, he passed away in Grand Rapids at the age of 39 years, 10 months and three days.

Frank was laid to rest in the Beaver Creek Cemetery, where many generations of the family are at peace in eternal sleep.

Nora's fate after that time is unknown.

|

Copyright © 2002-2003, 2007, 2011, 2021 Mark A. Miner |

|

Sketch of Libby Prison originally published in The Annals of the War (Philadelphia Weekly Times, 1879) |