| Home |

|

The

Elusive, Zigzag Search |

|

By Mark A. Miner |

|

|

In April 2014, during a visit to the Cornerstone Genealogical Society in Waynesburg, Greene County, PA, and after almost four decades of searching, I found a short newspaper obituary for my elusive third-great grandfather, Henry Minerd (also spelled "Minard," "Miner" and "Minor"), husband of Mary "Polly" Younkin. Or, as I had been calling him for years, “Mysterious Henry.”

I let out a whoop. As a journalist by training, I value news coverage as a way to document ancient lives, and that obituaries often provided the final word on one's legacy. In Henry's case, however, I had been looking for his obit for years, and long ago had given up hope that I would find one.

The irony is that my research path was thrown off course by a well-intentioned but aged uncle, working in the 1940s, who suffered from some key memory lapses, and whose facts were not entirely accurate, leading me to pursue dead ends.

I first became aware of Henry’s existence on Veteran’s Day 1977 when my mother braved a heavy snow to drive me to the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh where we found old census records on microfilm dating to 1850. In those listings, Henry and his wife Mary were shown to head a household of nine children near the village of Kingwood in Upper Turkeyfoot Township. Their son Andrew Jackson Miner, my great-great grandfather, was a four-year-old boy in the household at the time.

Henry and Mary disappeared from Somerset County census enumerations after that. My mind was fueled with questions. What had become of them?

At family reunions, I peppered my great aunts Jessie (Miner) Schultz and Anna (Miner) Neely with incessant questions They knew nothing about Henry, their great-grandfather, but recalled that their uncle, William Allen Miner, known as “Uncle Will,” had dug into the family history at one point. According to their stories, Uncle Will had prepared a report and said that the original spelling of the name was “Minerd,” a Pennsylvania German derivation.

|

|

| At Miner reunions in Washington PA in the 1970s, I spent a lot of time asking questions of my aunts. That's me at right, in the blue shirt and hat. |

|

|

| Letter from the Somerset County Register of Wills |

My letter to the Somerset County Register of Wills, in search of Henry’s paper trail, produced a reply dated Jan. 10, 1978 that “regarding your question concerning Henry Minard (Minerd). I have searched the records thoroughly and can find [nothing]… I have tried all possible spellings of the name.” At the Register’s suggestion, I wrote to the Somerset County Recorder of Deeds and obtained copies of deeds from when Henry purchased a 123-acre farm from the estate of his late widowed mother in the 1840s.

Later in 1978, while on vacation in California, my father took us to meet the elderly Laura (Thompson) Miner, who had been married to Uncle Will. I pestered Aunt Laura with family history questions but as she had married him later in life, she was unable to help.

In the late summer of 1978, with my curiosity remaining high, my parents took me to Kingwood to spend a day exploring. In an extraordinary turn of events, we met Mysterious Henry’s last living granddaughter, Minnie (Miner) Gary, residing in an old farm house along a lonely valley road. She allowed us to sit with her in her kitchen and told us a little more about Henry. She said that his wife’s maiden name was “Younkin” and that her regular name was “Polly,” a derivation of “Mary;” and that Polly suffered from epilepsy and once had a horrible accident when falling into a burning fireplace during an attack, burning off her ear and much of her head and face.

|

| Meeting Mysterious Henry's last surviving

granddaughter Minnie Gary in the summer of 1978. I'm in the back, with all the hair. |

I never saw Minnie again. Had I known what to ask at our first meeting, she could have directed me more precisely. But one doesn’t know what one doesn’t know, the foible of every family historian when at the outset of her or his quest.

Fortunately my mother took good notes during our Carnegie Library session. Her writing, in blue ballpoint pen on lined tablet paper, showed that Henry and Polly had moved away from Somerset County. In 1860 they were in Marshall County, Virginia (later West Virginia). By 1870 they were back in Pennsylvania, in Greene County, and remained there in 1880 as noted by the census-taker. It took several more attempts at the Carnegie Library to find and copy these documents.

Why had they moved away from their seemingly prosperous lives in Somerset County? And what were their final fates?

|

| The Miners' overgrown burial site on a

farm at New Freeport, Greene County |

In about 1988, I made a visit to Waynesburg and found a tax record stating that Henry had "gone - to the divil." What did that mean?

At the Cornerstone Genealogical Society in Waynesburg, at the time housed at the Bowlby Library, I found an index of local cemeteries compiled by Dorothy T. Hennen. The index showed that a “Henry Miner” had died in 1890 and his wife in 1886 and that they were buried in a small graveyard near New Freeport. In fact, Mrs. Hennen gave the unnamed cemetery the moniker of "Miner Cemetery," presumably since Henry's marker was the largest and most prominent.

But there was one confusing glitch – Henry's wife’s name was shown on the marker as “Nancy” instead of “Polly.”

Surely there was some mistake. I drove to New Freeport and with some guidance from locals was able to find the small “bury patch” which was all overgrown. I took photos from a variety of angles, and recorded the measurements -- the base measures 29 inches long by 19 inches wide and a foot high. Several other smaller grave markers were in a line and all were toppled over and flat, partially obscured by the elements.

At the next free opportunity, I went back to the Cornerstone facility and spent an entire day combing through microfilmed Greene County newspapers for 1890 and 1886, looking for their obituaries. The effort produced nothing, and was a waste of a day. Had Henry and Polly lived so poorly or obscurely that their deaths were not even given the dignity of a printed notice? Over the years I also searched old newspapers on film at libraries in Somerset, Meyersdale, Connellsville, Uniontown and Washington without result.

|

|

| Great-uncle Francis Riggs, retired local tombstone salesman, examining the marker |

I had a traveling partner during that time of my late great-uncle, Edward John Miner. He and I spent many weekends driving to visit distant cousins in southwestern Pennsylvania, Maryland and Ohio, all of whom potentially could have had knowledge of Henry. We met many great people and learned a lot of family history. But Henry's memory was lost to every single family with whom we visited.

My luck turned when I got the idea of contacting an expert in the family, my father’s maternal uncle Francis Riggs of Washington, PA. Uncle Francis lived in the county adjoining Greene and had spent his career selling grave markers all throughout the nooks and crannies of the region. I sent Uncle Francis a letter with some photos, and he wrote back, showing interest in seeing the actual thing.

First I need to see the stone to see what kind of material it is made from. It might be of granite but judging from photo I am inclined to think it is marble. Second, the granite industry started using this tipe of lettering around 1940... The name Miner is not a comon name in that area. It is going to be tought to run down.

So on a beautiful sunny autumn afternoon in 1990, Uncle Francis and his son Kyle and I drove to New Freeport. Uncle Francis studied the marker in detail and took measurements. His conclusion was that the work, with death dates of 1886 and 1890, was more modern than that, and could not have been produced before 1935. His rationale was that the finely inscribed letters could only have been done with sandblasting, a technology which did not exist any earlier.

Uncle Francis then suggested that I contact local monument companies in the hope that one of them had done the installation and still might have records. I called most of the prominent ones Francis recommended, only to be told records were gone or stored away or that no one had time to do a lookup. One company owner wrote back to say "The stone was not done by ... any reputable firm. I know this due to the several nicks in the stone at the joint."

|

|

| Uncle Will's contract with

Kurtz Monument, which cost him $75 in 1946 |

It was only on a final attempt, in contacting the last firm on my list, that I struck gold with Rock of Ages, otherwise known as Kurtz Monument Company.

A helpful person on the other end of the phone asked what name I was searching. Within 60 seconds she had found the original paperwork in the Kurtz files and was giving me the details. Yes, the papers confirmed that the burials were my people. Why was this suddenly clear? Because the person who authorized and paid for the stone was my father’s grand-uncle whose name I knew well – Mysterious Henry’s grandson – “Uncle Will.”

Copies of the contract were sent to me, and I had them in a few days. They showed that the marker was not installed until 1946, after nearly a half century had passed since Henry died. Why would my father’s uncle have done this after so many years had passed, and after he had spent most of his life in the Los Angeles area? One can only speculate that it was nostalgia. The papers show that he also ordered a second stone at that time from Kurtz for his recently deceased wife and infant son, whose grave in Washington (PA) Cemetery was relocated from one plot to another. A quick calculation showed that Uncle Will would have been age 14 at Henry’s death and 70 at the time the marker was produced, and possibly one of the few still living who remembered where his grandparents had lain for decades in unmarked graves.

And sadly, Uncle Will was losing mental balance at that point in his life, as he soonafter suffered a “nervous breakdown” and was hospitalized for some time at St. Francis Hospital in Pittsburgh, undergoing electric shock therapy. My father said that Will recuperated at my grandparents’ home in Aliquippa, PA and regained his mental health.

But why had Uncle Will used the wrong name on the marker – “Nancy” instead of “Polly?” I can only suspect that it was due to an old age memory lapse. The couple had a daughter Nancy whom Will would have known, Nancy (Minor) Farabee of Waynesburg, and he must have been confused although well-meaning when choosing the lettering for the project.

|

|

|

The Miner marker as photographed in 1988, during my first visit |

Thanks to connections made in the 1990s and 2000s at reunions of Henry’s in-laws, the Younkins, I was privileged to view letters written in 1935 by Charles Arthur Younkin that more completely documented Polly's story of the tragic fireplace accident. (See his letter dated Oct. 15, 1935.)

|

|

| Uncle Will, who purchased the marker for his grandparents when he returned to Pennsylvania to bury his wife Osta |

End of story, correct?

No. In the spring of 2014, while visiting the Cornerstone facility in Waynesburg, looking for obituaries of other ancestors, I saw an index listing for a “Henry Minor” who had died in 1888. Clearly, this could not be my man, as the grave marker stated his year of death as 1890, a discrepancy of two years. Surely Uncle Will would have known Henry’s death year as he was a teenager at the time and should have had a pretty good idea of the timeframe.

But in good conscience I looked up the “Henry Minor” death notice and – to my great surprise – discovered the one document that had eluded me for decades.

|

|

|

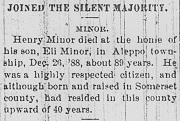

Waynesburg

Republican, |

Henry Minor died at the home of his son, Eli Minor, in Aleppo township, Dec. 26, '88, about 89 years. He was a highly respected citizen, and although born and raised in Somerset county, had resided in this county upward of 40 years.

In the conclusion of my humble opinion, and in the course of the research path I had taken, Henry’s legacy would not have been discovered without the extraordinary gesture of my Uncle Will in 1946 to mark his grandparents’ graves. I am grateful to this uncle, whom I never knew, to the many others along the way who helped point and shape and nudge the search. And, as it turned out, the highly organized, well trained volunteers with the Cornerstone Genealogical Society added a major boost to the effort.

|

Copyright © 2014 Mark A. Miner |

|

Miner Reunion and Minnie Gary photographs by the late O. Wayne Miner |