| Home |

|

How

Our Family Lost Its |

|

|

|

Anti-German propaganda, early 1900s |

The Germans have a saying -- “Wir sind ein volk” -- “We are one people.” As a family, while we have grown large in numbers and diverse lifestyles, our DNA and our sense of history are unique in uniting us.

Today, some 270 years after our common ancestors, Friedrich and Eva Maria (Weber) Meinert Sr., settled near Reading, Berks County, PA, few traces of the family's German culture remain. Yet the German language of the clan was dominant for about 135 years, from the 1730s to the time of the American Civil War. It's amazing these "Pennsylvania Dutch" traits lasted as long as they did.

At right, a World War I propaganda postcard depicts "Uncle Sam" chaining the German Kaiser as a prisoner, symbolizing the 20th century hatred that drove a deeper wedge between the American and German cultures in the United States.

|

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Digby Baltzell's authoritative and classic 1979 book, Puritan Boston & Quaker Philadelphia, says that the Meinerts' eastern/central "Pennsylvania Dutch country, the richest farming land in America, is a remarkably [culturally] homogenous area even today. Indeed, for a long time the area was bilingual; the so-called Pennsylvania Dutch dialect is a mixture of English and German."

While long-term assimilation is natural for any clan, other strong forces were at work to ultimately Americanize our family. Wright’s Franklin of Philadelphia states that Benjamin Franklin was partly to blame for being “especially critical of the Germans in western Pennsylvania” during the colonial era. Franklin wrote:

Why should the Palatine boors be suffered to swarm into our settlements and, by herding together, establish their language and manners to the exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us, instead of our Anglifying them?”

Legislation was introduced in Parliament in the 1750s that would have kept Pennsylvania Germans from voting, as Wright says, “until they had acquired ‘a sufficient Knowledge of our Language and Constitution,’ and requiring that all newspapers, almanacs, and legal documents in the province be written in English.” Under such restraints, it is little wonder that the German values were left behind.

After the end of the Revolutionary War, German ways and means became even more dominant in the region, and "its distinct dialect exaggerated the isolation of the area from the rest of the new nation," says Frantz and Pencak's 1998 book, Beyond Philadelphia. "Adding to this insularity was the inclination of the Pennsylvania German subculture to marry within its own community, to remain wedded to the soil, and perhaps to be more religious, superstitious, and suspicious of the outside world than others."

|

| Sidney George Fisher's A Philadelphia Perspective |

In July 1838, Philadelphia high society gentleman Sidney George Fisher took a rail trip through the state, passing near Reading, Berks County. He was appalled by what he saw in the epicenter of our family's Pennsylvania origins, and a hub for Pennsylvania German settlements. In his diary, later published in the book A Philadelphia Perspective, he wrote:

Never saw such farms, or such crops. Universal prosperity & rude plenty apparent everywhere, but no taste or refinement. Regretted that so fine a country should be possessed & marred by such boors. It is like seeing a beautiful woman, married to a vulgar & brutal man.... The pride of a dutchman consists in having an immense red barn, and a quantity of huge, fat, heavy horses. Never saw such large barns.

|

| Grave of Heinrich Gaumer in German script |

Yet despite such pressure, German continued to be spoken widely by succeeding generations of the family. It was one aspect of the culture -- the ease of communication among each other -- that would not be relinquished.

In 1828, John Minerd of Kingwood, Somerset County, PA, was sued by cousin John Younkin for speaking libel libel in the German tongue. In the presence of neighbors and friends, Minerd said "He stole a sheep, and I will prove it." Someone listening would have actually heard "Er hat ein shoaff gestohlen und ich wol es gut machen." He then added, in English, "He stole a sheep, and I will say so before his face and behind his back as often as he wants to hear it." Shifting back to German, he said "Er beist ein dieb." -- "He is a thief."

In 1865, John Minerd’s son Henry A. Miner likewise was sued for alleged slander spoken in German, of a more obscene nature. He accused a married man of taking a single woman behind a tree and making her squeal. The alleged words were "...hinner a bluck gotta und hut Sie moch greishe." The woman sued, complaining that the remark caused her to be "grievously hurt + injured" and that her life was "much the worse."

Many of the Johannes "Dietrich" and Maria "Elizabeth" (Meinert) Gaumer branch who remained in Berks and Lehigh Counties, PA, continued using German well into the late 19th century. Among the tangible points of proof is use of German script on grave markers. For example, In 1846, the grave marker of Heinrich Gaumer, a great-grandson of Friedrich and Maria, was so inscribed. Many scores of legible examples dot the graveyards of the Reading-to-Allentown corridor today.

~ Efforts to Preserve German Language and Culture ~

In heavily German populated cities such as Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and Milwaukee, special-interest groups were formed to preserve German music, church and social customs through the creation of institutional groups.

For example, Pittsburgh's Teutonia Männerchor ("German Men's Choir") was founded in 1854 as an offshoot of a German chorus called the Liederkranz. The Männerchor's aims then -- as they are now -- were to "further choral singing, our German cultural tradition and good fellowship." The Pittsburgh Männerchor today stands on Phineas Street in the North Side, with more than 2,500 members.

Many Pittsburgh churches were established where services were conducted in German, and some of their buildings stand today. More on this will be added here.

The Liederkranz movement spread across the nation, with permanent institutions established in such far-flung places such as Grand Island, Nebraska.

|

|

|

Liederkranz in Grand Island, Nebraska, to which belonged Edward Francis Younkin of the family of Col. John C. Younkin. |

~ Persecution of German-Americans During World War I ~

During the early 1900s leading up to and after World War I, it was highly unpopular to be known as German in the United States.

In one branch of our clan, who settled in Kansas and Missouri, the family purposefully altered the pronunciation of the family name during the war, possibly to escape some sort of persecution. According to one member of this branch:

Before World War I, the name was pronounced MY-nerd. It was German. When my brother, cousins and uncles returned from the war, they wanted no part of anything German. I remember my father and uncle talking about it more than once. And that was when our name was changed to the softer, French-sounding Meh-NARD.

|

|

|

In some cities, the anti-German bias reached levels of hysteria and irrational decision-making, as residents feared that German-Americans would have a strong loyalty to their native country. President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation condemning enemy aliens in the United States. The entire District of Columbia was designated as a "barred" zone, and "government agencies, charged with protecting the country from enemy agents, started to clean out many suspects employed in the government departments here," reported the Pittsburgh Press (Nov. 20, 1917).

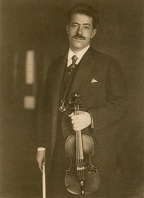

Performances of German music, especially, came under attack. In the Steel City, the Pittsburgh Orchestra Association (which may have been a front for the Woman's Club of Sewickley or perhaps the Daughters of the American Revolution) lobbied to forbid Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler from playing locally after he was accused of sending funds back home. The concert managers were denied a license from the local director of public safety in the belief that it would cause a disturbance of the peace. Four years earlier, Kreisler had served as an officer in the Austrian Army, as an ally of Germany, and was badly wounded in battle. With plans tour tour America in concert, he eventually gave up $85,000 worth of U.S. contracts to demonstrate his patriotism.

Pittsburgh -- which did not have its own symphony at the time -- also prohibited the visiting Philadelphia Orchestra from playing the works of Ludwig von Beethoven, "and the orchestra promptly decided to exclude German music from its programs altogether," reported Current Opinion (issue of February 1918). See also Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, "Pittsburgh Bans Beethoven!", March 6, 2007).

Cincinnati, with a heavy population of Germans, was one of the worst over-reactors. Headlines of the city's large, influential Cincinnati Enquirer of the period show violence and humiliation against Germans as well as changes of German-sounding public street names and elimination of German textbooks in local high schools.

|

Anti-German

Articles Printed in the Cincinnati Enquirer |

|

|

|

|

| Sept. 18, 1917 - German high school books denounced as propaganda and unpatriotic | Sept. 19 1917 - textbook censors condemn 6 German books in the high school library | March 31, 1918 - in fear that Germans of Cochocton, Ohio were holding secret meetings | April 9, 1918 - City Council votes to change the names of 12 city streets of German origin |

After the war, as the widespread ruins of Europe became widely known overseas, some Americans realized the "chilling lack of moral conduct and conscience by the enemy," wrote Martha Frick (Symington) Sanger in a biography of her great-aunt, Helen Clay Frick: Bittersweet Heiress. "To her,... the Germans were a cruel and heartless people who deserved to be distrusted, boycotted, disarmed, fined, and unilaterally rejected by the civilization it had almost destroyed. There was no telling when or if Germany mgith again rape Europe, its people, and its art."

~ Old Pennsylvania-German Folk Songs ~

Some old German songs continue to be passed down today though we don’t know what all of the words mean.

As a young girl, Nancy (Minor) Farabee was taught nursery rhymes or Mother Goose sayings, and recited one of them later in life to a young grandson, Donnus F. Farabee of Waynesburg, Greene County, PA. The words were pronounced as --

|

See-bee

quah-bee, English Mary, Singlum, sanglum, buck |

| Younkin cousin and genealogist Linda Marker provided this different version in the early 2000s as recited by her father in law of Somerset County, PA: |

|

Ornery,

orrey, ickery, a, |

A hybrid of German and English, this was sung in the farm fields of Somerset County, PA, by the late Minnie (Miner) Gary. It was passed down to her daughter, the late Gladys (Gary) Kreger:

|

E hope mutta en de Rabie carric (repeat 3 times) Way nibber en de Rabie carric awanie (onie) en de hymnal crom crafting mine mutta room Ugaena with angula en blonda rue (repeat 3 times) I have a mother in the promised land (repeat 3 times) When I get to Heaven then I will meet my mother there Gone with the angels to wear God's crown (repeat 3 times) |

~ Other German-American Words and Superstitions ~

Mary Adaline (Luckey) Malone recalled that "jangle" meant to argue or bicker. A granddaughter of Joanna (Minerd) Enos said that "grumbeer" meant potatoes.

James M. Enos often talked of seeing "ghosts and tokens" -- mysterious lights in the night sky signifying the spirit world was trying to convey a message of death. Amanda (Younkin) Hechler used herbal medicine and superstitions to help heal sickness. If one had warts, you were to cut slices of a raw potato, rub it over the affected area, and bury it in a place where rainwater would fall, and the warts would go away. Another time, one of her rose bushes bloomed in winter, and she feared that it was a "token" -- a sign that death was coming in the family. Within a month or two later, her own husband was dead. She also could take away the pain of a flesh burn by "blowing fire" -- putting salve on a burn, circling it with her finger, and speaking certain words, which invariably took away the pain.

~ Further Reading ~

"Pittsburgh and the Fall of the Berlin Wall," by Allyson Lowe and Paul Overby - Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Nov. 5, 2014

"Anti-German Sentiment Blocks Austrian Violinist" - Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Oct. 26, 2014

"Divided Loyalties: How the Outbreak of World War I Affected Pittsburgh's Germans and Their Downtown Church" - Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 27, 2014.

"German Ancestry Is Tops in Region" - Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 2, 2002.

|

Copyright © 2000, 2002, 2009-2010, 2013-2014, 2021 Mark A. Miner |

| Benjamin Franklin portrait originally published in American Statesmen - Benjamin Franklin, by John T. Morse, Jr. (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Riverside Press, 1898) |