|

Henry

C. Ullom (1840-1864) and

|

|

Andersonville Cemetery |

Henry C. Ullom was born on May 25, 1840 in Greene County, PA, the son of Peter and Matilda (Kinney) Ullom.

He was a Civil War soldier who died as a prisoner of war in the Confederacy's notorious Andersonville Prison.

On Feb. 10, 1861, at the age of 21, Henry married 21-year-old Hannah Neel (or "Neal") (1840-1896), daughter of Mary (Williams) Neal. Justice of the peace John T. Elbin officiated.

They produced one daughter, Mary Matilda Ullom.

One month and a day after his daughter's birth, and some 19 months after the Civil War erupted, Henry went to Camp Howe in Pittsburgh. There, on Nov. 21, 1862, he enlisted as a private in the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Company A. His term was set at three years. Former comrades Joseph Cook and John Fry recalled that "he was a man of Good health, not diseased, before he entered the service."

Early in his military tenure, Henry and the 18th Cavalry were stationed in the vicinity of the District of Columbia, defending the city against possible enemy invasion. During Gen. Robert E. Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania, the 18th Cavalry saw action at Hanover (June 30, 1863) and Gettysburg (July 2, 1863). The Gettysburg fight took place at the very southern tip of the battlefield near Big Round Top. The 18th was part of what scholars have called a "suicidal attack" led by Gen. Elon Farnsworth. Under heavy fire, the 18th retreated, and Henry was spared injury.

Later, the 18th was involved at Brandy Station, Germania Ford (May 4, 1864), Kilpatrick's Raid (Feb. 28, 1864), Spotsylvania, Yellow Tavern (May 11, 1864), White Oak Swamp and Winchester (Sept. 19, 1864). On Oct. 19, 1863, the 18th was engaged in fighting at Haymarket in Virginia. A month later, on Nov. 18, 1863, while posted near the Rapidan River, Henry was captured. He was sent to Andersonville prison in Georgia and was held there for nearly 11 months.

|

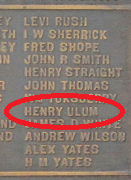

Above: Henry's misspelled name on the Pennsylvania Monument at Gettysburg. Below: the Gettysburg marker honoring the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry at the southernmost tip of the battlefield. |

The following June 1864, while still incarcerated, he met up with his former cavalry mate Joseph Cook, who also had been captured more recently in or around Old Church, VA. Henry and Cook apparently remained together during the rest of their ordeal.

But faced with starvation, illness and widespread filth, Henry died of tuberculosis (scrofula) on Sept. 2 (or 22), 1864, and was buried under the name "H. Woolman" (Grave 9534). Friend Cook later testified that he "seen after he was dead and laid out" and that "he has no doubt that the disease which caused his death was brought on by starvation."

His name also was spelled in military lists "Ulum" and "Ullem." At some point, the grave marker was replaced with both first and last name and correct spelling -- "HENRY ULLOM."

|

|

|

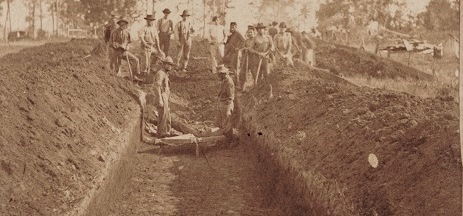

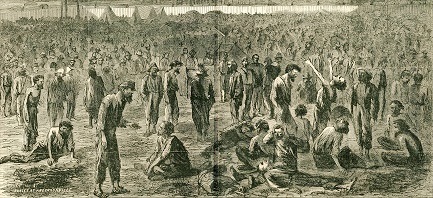

Above: Rare image of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry in camp near Brandy Station, VA. Note crude log huts for soldiers and fenced pens for horses. Below: Andersonville POWs, where Henry perished after 11 months in captivity. |

|

|

Official history

of |

After his death, widow Hannah petitioned for and was awarded a pension as compensation for her loss. On Jan. 23, 1868, she began receiving payments of $8 per month, retroactive to the date her husband died. Over time, the payments were raised to $12 per month. Mary Neel and Thomas Neel, her kinsmen, provided testimony in support of her claim.

Hannah remained in Aleppo Township, near the post office at Spraggs, and was a member of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church at Jacksonville (Jacktown). She refused offers by others to adopt her daughter.

The federal census enumeration of 1870 shows Hannah and daughter Mary living with Hannah's widowed mother, along with 23-year-old Elizabeth Neel and 19-year-old Mary Neel. Their post office that year was in Rogersville, Greene County.

By 1880, Hannah lived alone in Center Township, Greene County.

|

|

|

McVay Cemetery, where Hannah rests |

Hannah passed away at the age of 56 years, four months on Aug. 14, 1896. An obituary in the Waynesburg Democrat reported that "She had been an invalid for several years, but death came at last and called her home."

Burial was in the McVay Cemetery in Aleppo Township, following funeral services led by Rev. J.M. Murray. On her grave marker, her age was inscribed as "66 Yrs.", but this is incorrect by a factor of 10 years. [Find-a-Grave]

Documents in Hannah's pension file were placed in the National Archives in Washington, DC, where they remain today. The papers were examined personally in 2014 by the founder of this website, and copied. The copies today are housed in the Minerd.com Archives.

In 1909, Henry was named in a book about his Civil War regiment, History of the Eighteenth Regiment of Cavalry, Pennsylvania Volunteers, authored by by Theophilus Francis Rodenbough and Thomas J. Grier (page 191).

|

Clara Barton |

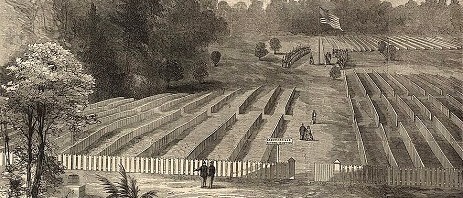

Henry's legacy might today be otherwise forgotten, and his family forever kept in the dark about his fate, but for the heroic private action of an Andersonville POW named Dorrence Atwater. It was Atwater's job at the camp to keep an official list of the 13,000 names of the dead and their precise burial sites which were in very shallow trenches. Despite the extreme conditions, he managed to maintain a secret duplicate copy which he stored in the lining of his coat. Wrote famed Civil War nurse and American Red Cross founder Clara Barton, "Day by day he watched the long trenches fill with the naked skeletons of the once sturdy Union Blue, -- the pride of the American Armies, -- and day by day, he traced on the great brown pages of his Confederate sheet record, the last, and all that was ever to be known of the brave dead sleepers in their crowded, coffinless beds, -- the name, company, regiment, disease, date of death, and number of grave." At the war's end, Atwater shared the list with Barton who in turn advised the Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. At Stanton's order, Atwater, Barton, Army Assistant Quartermaster James Moore and a team of painters and carpenters traveled to the prison site. The men labored in the searing heat of the Georgia summer, exhuming the corpses, placing them in proper caskets, reburying them in deeper graves of four-foot depth and conducting Christian funeral services. Each grave was marked with a headboard identifying the soldier, and she wrote dozens of letters to grieving families to let them know of their loved one's fate. With the reburial project complete, a dedication ceremony was held on Aug. 17, 1865, where she was invited to raise the American flag. The event was so meaningful in the American psyche that a sweeping sketch was published in Harper's Weekly a few months later, on Oct. 7, 1865. Of that ceremony, she wrote her observation: "Then I saw the little graves marked, blessed them for the heartbroken mother in the old Northern home, raised over them the flag they loved, and died for, and left them to their rest. And there they lie to-night, apart from all they loved, but mighty in their silence, teaching the world a lesson of human cruelty it had never learned...."

|

Above: proper reburials of the dead at Andersonville. Library of Congress. Below: Clara Barton at the dedication of the cemetery, Aug. 1865. Harper's Weekly, Oct. 7, 1865. |

|

~ Daughter Mary Matilda Ullom ~

Daughter Mary Matilda Ullom (1862- ? ) was born on Oct. 20, 1862.

At the age of 9, she dwelled with her mother, widowed grandmother and two aunts in Aleppo Township, Greene County.

Her fate is not yet known.

Copyright © 2014, 2018-2019 Mark A. Miner |

Clara Barton quotes originally published in The Life of Clara Barton, by Percy H. Epler, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1915. |