|

First Fight, First Blood |

| Alexander White, the 12th West Virginia Infantry and the Second Battle of Winchester and Their Legacy on One West Virginia Family |

|

By Mark A. Miner |

|

|

|

|

| Civil War statue, Moundsville |

FOREWORD (by Robert Grogg, editor of the Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society Journal) - This account reminds us that the Civil War was an unparalleled tragedy for this nation and that both North and South suffered grievously and that much of this suffering took place in the streets and neighborhoods through which we all pass as we go about our lives in the latter years of the 20th century.

Pvt. Alexander White died more than 125 years ago, in June 1863, a casualty of the Civil War. He passed away after his right leg, ripped apart by a Confederate shell, was amputated by a Union Army surgeon in a hotel turned makeshift hospital. He died 125 miles from home, far away from his wife and four young children.

He died following his regiment's first battle of the war, defending a town whose residents resented his presence and that of his fellow blue-clad soldiers. In a final twist of indignity, he was buried so hastily and with so many other of his dead comrades that no stone marks his final resting place. Alexander White fought and gave his life in a place called Winchester, Virginia.

Unknown, Winchester

This article is about White, some of his comrades, and the role of the 12th West Virginia Volunteer Infantry during the Second Battle of Winchester, June 13-15, 1863. This is a story about a failed attempt by the Union to hold back a Confederate onslaught in a battle that was overshadowed by another two weeks later in Gettysburg.

It is also about a farm estate in Winchester called Glen Burnie that began to become recognized as a strategically important Civil War site in the late 1980s. In 2004, the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley was built and dedicated on the very same battlefield, in what is a truly remarkable coincidence.

~ Prelude to Battle ~

The townspeople of Winchester and the soldiers of the 12th West Virginia first met on Christmas Eve 1862, when the 12th entered town after a long march from Strasburg, Virginia. There originally were approximately 950 soldiers in the 12th West Virginia. Along with some 6,000 Union soldiers from other regiments, they were assigned to Winchester to keep an eye on Confederate operations in the Shenandoah Valley. Winchester was a particularly important place, a hub of roads leading to West Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley, and the Winchester and Potomac Railroad line began there and ran 32 miles to Harpers Ferry. It was considered especially strategic by Maj. Gen. Robert H. Milroy, whose steadfast belief in holding the town would lead to the destruction of his army and bring about his own humiliation.

|

|

|

Advance of the Union Army - occupation of the abandoned Confederate fort in Winchester by a detachment of General Banks division, March 1862 |

|

|

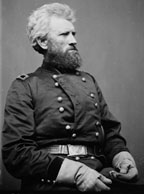

Stern looking Milroy |

Milroy was in command of the three brigades of the 2nd Division, 8th Corps, comprising all of Union forces in Winchester. There were seven regiments in the 2nd Brigade, one of which was the 12th West Virginia. The 12th was under the command of Col. John B. Klunk. When it entered Winchester on Christmas Eve, the regiment was just four months old and had not seen any fighting. One of the 12th 's officers was Maj. Francis H. Pierpont, who would later accept an appointment as the first Adjutant General of the newly created state of West Virginia. Pierpont liked his regiment; he remarked that it was “a splendid set of fellows.” The soldiers themselves were mostly West Virginians, with a few Pennsylvanians and Ohioans. Assigned in Winchester to routine guard duty and scouting, they often wondered if they would ever get into a battle. Some boasted that they were “spoiling for a fight” if they could get one. Within six months they would indeed get a fight. For some, like Alexander White, the experience would come at the cost of their lives.

A majority of Winchester's 3,500 citizens hated the Union occupation of their town, and especially felt contempt for Milroy. The general, in turn, did not like the citizens; he took pains to check and control their day-to-day activities. One of the townspeople was 43-year-old Mary Greenhow Lee, who lived on Market (now Cameron) Street and kept a diary. Mrs. Lee and others were required to have a special permit to buy food at the local store. She wrote: “For months [we have] been ground down, every word and action misconstrued, surrounded by spies, having to resort to artifice to obtain the bare necessities of life.” Union troops were ordered to tear down the Winchester home, Selma, of James M. Mason, the prominent Confederate diplomat.

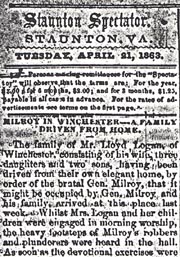

Staunton

Spectator article

Milroy was vilified by Confederate city newspaper articles as "brutal" and worse. The Staunton Spectator, for example, published a scalding piece in April 1863 about how Milroy's "robbers and plunderers" took possession of the home of Lloyd Logan in Winchester even while his family was attending Sunday worship services.

vilifying Gen. Milroy

Milroy's headquarters were in a fort west of town. It was called Fort Milroy or later Fort Garibaldi, but for purposes of this paper will be called “Main Fort.” It was located were the Whittier Acres subdivision is today. About 1,500 yards to the west of Main Fort was a smaller, earthen fort not yet completed called West Fort. Both would be focal points of the Confederate attack in June 1863. For the first three months the 12th West Virginia was in Winchester, wrote regimental historian William Hewitt, "little of important interest took place."

~ Winchester's Importance ~

The Confederate Army in June 1863 was a hungry one. Two years of fighting had drained the south of able-bodied farmers as well as the vast resources of food needed for its soldiers. Confederate officials knew that foodstuffs and other key supplies were available in the north. That was but one of several strategic reasons the Confederates decided to mount an invasion. Another was to put pressure on Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., and to keep the Union forces too busy to attack Richmond, the Confederate capital.

A third reason was purely economic. John B. Gordon, a Confederate general whose troops would later go head to head with the 12th West Virginia, wrote: “It was hoped that a defeat of the Union… [near] these great cities would send [the price of] gold to such a premium as to cause great financial panic in the commercial centers, and induce the great business interests to demand that the war should cease.

The Confederate soldiers had begun to move northward in early May 1863 following the South's victory at Chancellorsville, Virginia. The objective was to meet up with Brig. Gen. William E. Jones, who had about 6,000 troops stretched throughout the Shenandoah Valley, and with Brig. Gen. J. D. Imboden, who had about 1,500 men in the Cacapon Valley. They planned to head right toward Winchester.

|

|

|

Remains of the earthen Star Fort ringing Winchester |

Winchester had been the site of an important battle one year earlier. Part of that battle had taken place on May 25, 1862, on land that was part of an estate called Glen Burnie. Confederates led by Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and Gen. Richard Taylor had attacked a federal brigade led by Col. George H. Gordon, in a line of battle parallel to and alongside a stone fence marking Glen Burnie's southern border. After three hours of heavy gunfire, the Union brigade withdrew and retreated out of town.

In June 1863, when the Confederates again targeted Winchester, Union officials somehow decided that Winchester was strategically unimportant . On June 11, 1863, Milroy received a telegram from his superiors at Harpers Ferry suggesting that he “immediately take steps to remove [his] command…Send back [all] heavy guns, surplus ammunition, and subsistence.” Milroy refused and wired back, “I have the place well protected, and am well prepared to hold it….I exceedingly regret the prospect of having to give it up. It will be cruel to abandon the loyal people in this country to the rebel fiends.” Maj. Gen. Robert C. Schenck, Milroy's immediate superior, responded: “You will make all the required preparations for withdrawing but hold your position in the meantime. Be ready for movement, but await further orders.”

~ Eve of Battle ~

|

|

Marker in Winchester |

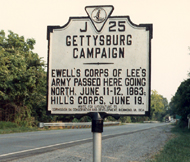

In the weeks leading up to the battle, Winchester had not been altogether quiet. Small bands of Confederate cavalry had made it a routine practice to ride close enough to town to be “seen.” Milroy made it a practice to send his own cavalry out to chase them away. As time passed the Confederate feints grew bolder. On June 12, two of Milroy's scouting parties surprised a group of Confederates near Middletown, 10½ miles to the south, killing or wounding 50 and taking 37 as prisoners. Upon questioning, the prisoners convinced Milroy that there were no other confederate forces nearby. What Milroy did not know was that even as he was grilling the prisoners, 40,000 Confederates were quietly filing north across the Blue Ridge at Chester Gap, just 22 miles from town. The surge of the 2nd Army Corps, under the command of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, was about to pounce on the unsuspecting Milroy the very next day.

Milroy received no further orders from his superiors to evacuate. When Schenck finally gave a clear order for Milroy's retreat, on June 13, the day the battle began, the transmission was never received. Somewhere along the route the wire had gone dead.

~ The 12th Prepares ~

The Union forces at Winchester nonetheless were kept busy and on alert. About 1 a.m. on June 13 the soldiers of the 12th West Virginia were awakened and ordered to pull down their tents, load them into wagons and prepare to take battle positions. By 8 a.m., with nothing having happened, the men were ordered to pitch their tents again. Having done this, they were ordered to take them back down. Tensions no doubt were high; a spirit of excitement was in the air.

|

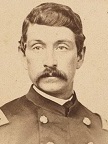

| Clockwise from upper left -- other members of the 12th West Virginia: Capt. Thomas A. Fleming, Co. F -- Capt. John R. Brenneman, Co. K -- Pvt. Joseph McCauslin, Co. D -- hospital steward Charles Henry Odbert, Co. K -- 1st Lt. James C. Pierson, Co. D -- Capt. William L. Roberts, Co. A and C -- Maj. Richard Hooker Brown, Co. I. Library of Congress |

|

Col. John B. Klunk of the 12th West Virginia had much on his mind during those wee morning hours. A resident of Grafton, Taylor County, West Virginia, he enlisted at Wheeling in August 1862 as a colonel. He was regarded by his superiors as “an amiable, excellent officer,” and no doubt he was devising strategy if his regiment should go into battle. But he was surely fighting pangs of homesickness. Earlier in the year he had tendered his resignation so that he could return home to his wife of 26 years, Margaret (Frost) Klunk, and their children. The resignation letter, however, was returned for his reconsideration. Klunk then asked for a 20-day leave of absence. “I have a large family of children to support,” he wrote, “with no one to govern or control them — except my wife — who is very much afflicted. I consider it my sacred duty as their parent to have them schooled and provided for — which cannot be done without my personal supervision and attention.” Klunk got 15 days furlough in April 1863 but it lasted only four days. He was abruptly called back into duty because of Confederate raids near his hometown of Grafton. When that threat ended he was ordered to return directly to his regiment.

Also preparing himself in the early hours of June 13 was Dr. Frederick H. Patton, a 22-year-old who was permanently assigned to the 12th West Virginia as an assistant surgeon. Patton stood six-foot-one, dark hair, dark eyes and a dark complexion, and was in robust health. A native of Morgantown, WV, Patton had studied at Georges Creek Academy near Uniontown, PA, and later graduated from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, with his uncle, Dr. Henry Bernard Mathiot (1815-1894), as his preceptor. It was Patton's usual custom to walk along with the regiment on its marches, while he allowed sick soldiers to ride on his horse. Young, strong, and well-liked, Patton's devotion to his regiment would cost him dearly. The battle to come would trigger a series of events that would break his health and cause him unending, excruciating pain throughout the remaining 30 years of his life.

~ Alexander White's Background ~

What thoughts went through the mind of 37-year-old Pvt. Alexander White on the morning of June 13 can never be known. As a young man, in 1850, he had resided on a farm with his sister and brother in law, Sabina (White) and Josiah Simms, near Cameron, W.Va. Tragedy would stalk the Simms family, as three Simms children would die young by 1859, their mother Sabina would die at age 33 in 1858, and Josiah himself would go on to a tragic outcome during the war.

By 1851, Alexander had married Eliza (Miller) White. They went on to have four young children — Margaret, Frank, William, and Jane. The Whites lived before the war in rural Liberty Township, Marshall County, W.Va., where Alexander worked as a farm laborer along Bowman Run. The Whites were very poor, owning no land, although he was a trustee for a schoolhouse/church building “on the waters of Big Run of Fish Creek.”

He had enlisted in the Army in August 1862 perhaps out of loyalty to his state, perhaps to draw a private's regular monthly salary of $13. Writing in the history of Alexander's regiment, author William Hewitt said:

The Twelfth was made up of exceptionally good material. The men were mainly American born and native Virginians. they were a hardy, robust, vigorous, self-reliant class of men, mainly from the farming districts, of more than average size, many of them mountaineers. They enlisted under trying and embarassing [sic] circumstances, and in great measure from patriotic impulses, their surroundings and circumstances in many cases tending to lead them to join their fortunes with the Rebel cause. It was a common thing for a West Virginia Union soldier to have friends and relatives in the Rebel army, and in some cases for brother to fight against brother.

Between August 1862 and June 1863 he was present with his regiment at all times except for a five-day furlough in October, when he returned home. It was the last time he saw his family. Little else about him is known except for his fate.

~ First Fight: June 13 ~

The Confederates camped at Front Royal the night before their planned attack. At 3 a.m. Ewell wakened his divisions and ordered them to march north toward Winchester. Reporting to Ewell were two divisions, headed by Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early and Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson. Each division had four brigades. Ewell's 40,000 troops forded the Shenandoah River and marched on the Shenandoah Valley Turnpike (now U.S. 11) to a spot 3½ miles from town, arriving at 8:30 a.m. Ewell then ordered Gen. John B. Gordon's brigade to move to the left of the road and to form a line of battle. Gordon obliged, and his brigade followed. The brigade consisted of six Georgia regiments: the 13th, 26th, 31st, 38th, 60th, and 61st.

At 8 a.m. Milroy's scouts returned from their daily patrol to report seeing a large force of the enemy approaching from the south. This took Milroy by surprise. He ordered detachments from his army to march south of the town and form battle lines.

One of the regiments sent on this assignment was the 12th West Virginia. It took a position to the west side of the Strasburg Road, now known as Middle Road. It must have been an impressive sight: hundreds of men marching in their heavy, dark blue coats, thick trousers and thick felt hats. When lined up in double rank they would have measured about 277 yards end to end. Each man carried a full compliment of a carbine rifle, canvas haversack containing food, a canteen of water, a knapsack holding blankets, and a cartridge box of ammunition.

The 12th waited from about noon to 2 p.m. in its position just off the Strasburg Road. The men heard cannon fire to their left. They knew that the battle was on, but they could see nothing. At 2 p.m. the 12th was ordered back toward town; it was to take a position near Abram's Creek to support a battery of artillery guns sitting on higher ground behind them. Again the 12th waited. Finally it was ordered to march back to its original position just off the Strasburg Road.

That is where the fight began.

The 12th got its first glimpse of the enemy, coming out of the woods to the south: two lines of Gordon's 2,000 infantrymen. The 12th took a position on a wooded hill, with a cleared field and then another wooded hill beyond, where the enemy stood in perfect line. Union artillery from behind the 12th 's line opened fire on Gordon's men. Several members of the 12th, including Alexander White, were ordered to move forward while the rest of the regiment stayed behind as reserves. Their role was to exchange gunfire with the enemy and thus hold them in check, a technique called skirmishing. Gordon's Confederates, under heavy fire from the federal artillery and from the 12th 's skirmishers, doubled their own line of skirmishers and kept up a heavy barrage of return gunfire.

At about this time the men of the 12th were ordered to remove their bulky and uncomfortable knapsacks and to pile them together in the woods. While the firing continued, the 12th 's men could hear whistling noises in the air but could not identify the sound. One of the 12th 's officers, hearing his men talk about the strange sound, said “Boys, those are bullets as sure as you live.”

During the exchange of gunfire, an Irish private in the 12th had the hammer of this rifle shot off by an enemy bullet. He reached for his knapsack, forgetting that he had removed it earlier. Turning to an officer, the Irishman said, in his thick brogue, “Captain, captain, the bloody rebels have cut ahff my supplies.”

|

|

|

Hillman's toll gate along the Valley Pike one mile south of Winchester, near where much of the June 13 fighting took place |

The gunfire lasted for two hours. Civilians in town climbed to the rooftops to watch. Gordon ordered two of his reserve units, plus some cavalry, to join his skirmishers and mount an attack toward the right-hand side of the 12th 's line. The confederates gained several hundred yards of ground, forcing the 12th 's skirmishers back to a position behind a stone fence. The pressures on the right side of the 12th 's line was too much, and Klunk gave the order to retreat. But instead of having his men do an about-face and walk away from the line of battle, he had them turn 90 degrees to the left and march along the line of battle, and then at a designated spot turn left again and march away from the enemy. It was an odd strategy and was questioned by the men among themselves, but it was obeyed. In the haste to retreat, the 12th 's knapsacks were left behind. Recalled 1 st Lt. William Hewitt of the 12th : The knapsacks “fell into the hands of the Johnny's, who no doubt, examined them with a good deal of interest.”

Upon arriving back near town, Klunk's regiment crossed Abram's Creek and spent the night camped at the southern end of town. The first day's fight by the 12th was certainly not bad for an inexperienced group, and drew mixed reviews from one member of the enemy. During the day's fight, W.C. Mathews of the 38 th Georgia watched as the 12th skirmishers broke ranks and ran “in every direction, throwing away their guns and everything else. We… shot at them as they ran, and poor devils, we slaughtered them like dogs. I never saw so much running and screaming in my life.” Mathews did admit, though, that “the infantry had a little more spunk… [and] thought themselves a match for us.”

The 12th 's Hewitt, as could be expected, gave his unit much higher marks, especially Alexander White's Company B. “It is simple justice to say that the manner in which Company B [performed] on the first day's engagement, as skirmishers, called forth deserved praise,” he later wrote.

Casualties for the first day were lopsided: Gordon's brigade of Confederates lost 75 men killed or wounded. Klunk's 12th West Virginia lost but one officer, six men killed and 16 wounded. Young Dr. Frederick Patton of the 12th had his hands full that night, helping to treat the wounded and the dying. White survived the first day unscathed. Back at the Union headquarters at Main Fort, Milroy felt that he could still hold Winchester for five more days, provided that reinforcements were provided. In fact, Mrs. Mary Lee, the diarist, wrote that night: “[Milroy] says he will see the town streaming with blood from one end to the other before he will give it up.”

|

Copyright © 1989-2013 Mark A. Miner |

|

Revised and expanded from the original published in the Journal of the Winchester- Frederick County (VA) Historical Society - Vol. IV, 1989. |

|

Staunton Spectator newspaper article copy courtesy of Ben Ritter. Milroy photo courtesy of the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress. All other images © Mark A. Miner or courtesy of the Minerd.com Archives. |