|

First Fight, First Blood (continued) |

|

|

| Battleground of June 14, 1863 -- with Glen Burnie to the far right -- as taken from the city's water tower in 1989. The Confederate position was at left. |

~ Confederate End-Around: June 14 ~

Day two of the fighting at Winchester was a strategic and tactical triumph for the Confederate forces. They mounted such intense pressure upon Milroy's federals that he was forced to flee from his preciously held town in the dead of night.

A tremendous rainstorm drenched Winchester in the early morning hours of Sunday, June 14. At daybreak the rain ceased, and it began to get hot. To get a good look at the enemy, Milroy rigged a basket and was hoisted up the flagpole at Main Fort, to a height of about 50 feet. He spent part of the morning looking through his telescope, trying to determine from which direction the Confederates might come. A scouting party returned at 2 p.m. to Main Fort to report seeing none of the enemy from the west. Milroy took this as evidence that the Confederates were not going to attack but instead were going to bypass the town and advance to Harpers Ferry. This, of course, was not true.

Meanwhile, in the confederate camp south of town, Ewell and Early met at 9 a.m. to devise an attack strategy. They decided that their strongest point of attack would be from a wooded hill to the west of town. This hill overlooked the earthen West Fort, which was about 1,500 yards from Main Fort. The generals assigned this task to the brigades of Gen. William Smith and Gen. Harry T. Hays. Smith's and Hays' task was first to make a charge from the south and then to retreat as if beaten back. Smith and Hays were then to circle quietly from south of town to the west, unseen. While they were circling, two other brigades would cause a diversion from the south and east to keep the Union forces occupied. This diversion was assigned to Gen. John B. Gordon, who was to work the plan from the southwest, and Gen. Edward Johnson, who would work from the east. Gordon's troops had fought against the 12th West Virginia the day before, and would do so again that day.

For the exhausted men of the 12th West Virginia, there had been little to eat, except for a few crackers, and little sleep since the fighting the day before. At 2 a.m., the 12th was awakened and ordered to march from its camp south of town into the Main Fort. Then at 6 a.m. it marched out of the fort and headed south across Romney Road, now Amherst Street. The 12th advanced toward the mansion called Glen Burnie, the stately old home of Col. James Wood, founder of Winchester.

|

|

|

Glen Burnie in an old postcard image |

Passing Glen Burnie, the 12th continued marching through a pasture to a stone fence marking the southern edge of the property, about a quarter-mile south of the mansion. This fence was five feet high, three feet thick and ran in an east-west direction for about 850 feet. The fence had been the site of fighting the year before, and now, by nightfall, it would again be the focus of attacks by both armies.

When the 12th reached the stone fence, it saw the enemy approaching from the other side. Confusion ensued. Several companies of the 12th's left side broke and ran back through the pasture to a knoll about two-tenths of a mile away, remaining there until the afternoon. A large number of the 12th held their position, crouching behind the fence for cover. The Confederates meanwhile scrambled to a stone fence parallel and about 150 yards from the Glen Burnie fence. Both sides exchanged fire and skirmished throughout the morning and early afternoon.

|

|

|

View that the 12th West Virginia would |

From time to time Gordon's Confederates advanced skirmishers toward the Glen Burnie stone fence but were repulsed by heavy fire from the 12th and from a battery of federal artillery firing long-range from Main Fort, about half a mile away. Gordon's “attacks” toward the fence were in reality bluffs, but they certainly looked real to the 12 West Virginia. During the exchange of fire, some members of the 12th watched with delight as the artillery guns at Main Fort did some very accurate shooting. Wrote Lt. Hewitt of the 12th , the artillery “knock[ed] several holes in the wall behind which the Johnnys were, causing them…to scatter in a lively manner…and thus from both sides became hot, hungry, and tired. Second Lt. John T. Ben Gough of the 12th stretched out to take a nap. A Confederate sharpshooter took aim at this target and easily hit his mark. The wounded officer was brought off the pasture and taken into town to the Taylor Hotel, on North Loudoun Street, which was serving as a makeshift hospital. The lieutenant died that night.

At about 4 p.m., Milroy rode out to the Glen Burnie battlefield to better see the action. He then ordered the 122 nd and 123 rd Ohio regiments, a battery of artillery, and reserves from the 12th West Virginia to join the 12th 's skirmishers near the fence. From there they were to jointly launch an attack. Seeing help coming, the 12th 's skirmishers jumped over the fence and moved forward toward the enemy's fence. The two Ohio units halted at the Glen Burnie fence, however, and instead of jumping over, began to retreat. The 12th West Virginia's reserve soldiers also halted at the fence; the skirmishers, left alone out in the open, were forced to return to the fence for protection. The gunfire from the Confederates was so heavy at this point that the soldiers of the 12th could not even stand behind the fence but had to crouch down. Seeing no chance at further forward movement, Klunk ordered his regiment to retreat as well. By the time the soldiers crossed back over the Glen Burnie pasture, past the mansion, and across the Romney Road (about 5 p.m.), the enemy was close on their heels and began artillery fire of its own. The 12th was the last unit off the field.

|

|

|

R. Lee Taylor,

Glen Burnie caretaker, at the |

It was at sometime during the day's Confederate bombardment that Alexander White was hit, struck in the right leg by an artillery shell. With his leg is shreds, he was carried off the battlefield to a medical station — most likely in the Taylor Hotel. At the makeshift hospital, Dr. Patton and other surgeons treated the wounded, working non-stop without food or sleep. White's leg was in such poor condition that a decision was made to remove it. Lying on a surgeon's table, or perhaps a hotel bed, White was probably given a dose of chloroform. Surgeons tied a tourniquet on his leg to stop the bleeding, and, presumably holding a chloroform-soaked rag over his face, sawed through what was left of the shredded muscle and bone, and took off the leg.

The confederate strategy at Glen Burnie had worked, keeping the Union occupied all day. Soldiers of the 110th Ohio regiment, assigned to guard the West Fort and thus guard the western approach to Main Fort, spent the day looking through their telescopes, watching the Klunk-Gordon skirmish. The Ohioans thus had no idea that more than 10,000 Confederates had completed their circling sweep and had massed on a hill that was to the west of, and higher than, West Fort. To the east of West Fort was Main Fort, and then farther east was the town. Under command of Smith and Hays, the Confederates quietly prepared 20 artillery guns to rain down a shower of deadly shells. They opened fire at 5 p.m. Completely surprised, the 110th Ohio tried in vain to return fire, but were silenced within 45 minutes. Hayes then ordered his infantry to attack; they ran down the hill and swarmed into West Fort, taking it with ease. The Ohioans, with 40 men killed, wounded or captured, retreated to the protection of Main Fort, 1,500 yards to the east. There they joined the rest of the Union troops who had withdrawn into Main Fort.

|

|

|

Sketch of the battlefield, documenting |

The townspeople were both terrified and ecstatic. Mrs. Cornelia McDonald, like Mrs. Mary Lee, kept a daily diary and wrote many words that day. Her home along Romney Road sat directly on a line between Glen Burnie and Main Fort, the line of the 12th 's retreat. She watched the bloody battle with fascination. She wrote that night: “It seemed as if shells and cannon balls poured from every direction at once. One battery from the hill opposite our house rushed down and through our yard, their horses wounded and bleeding, and men wounded also, and pale with fright. …Hurrying groups of stragglers, and officers without swords, and some bareheaded. They were all hastening up to the fort which they imagined was a place of safety.” Many men crowded onto Mrs. McDonald's porch and into her house for temporary safety, while others outside the streets were full of turmoil. “Ambulances were backed up to let out their loads of wounded,” she wrote, “and horses reared frantic with pain from their bleeding wounds. Some were streaming with blood, and looking wild, and their poor eyes stretched wide with pain and fright. …All the while the batteries thundered, the booming of cannon, the screaming of shells (who that has ever heard that scream can ever forget it?).”

Mrs. Lee, watching similar scenes several blocks away, wrote: “It is terrific to know human beings are being hurled into eternity, perhaps unprepared, whether friends or enemies, but it adds to the horror when we know so many of our friends must be suffering from wounds, [and] we cannot get to them, to give them comfort.

With his troops safely inside Main Fort for the night, Milroy braced for a Confederate attack. It never came. Early was so satisfied with the progress of his men that he ordered them to settle in for the night. Early's troops at this point were within a mile of town on its east, south and west sides. During the night Early ordered all of the captured guns to be pointed toward Main Fort, and prepared them to open fire at first light, in conjunction with attacks by Gordon from the south and Johnson from the east.

While pondering over the day's events, Milroy certainly was bewildered by the strength of the Confederate surge. About 10 p.m., he held a high-level meeting with his three brigade commanders. Convinced that they were nearly surrounded, except to the north, they considered their options. They were faced with less than one day's supply of rations. Their supply of artillery shells was almost exhausted. Their only alternative was a nighttime escape. Milroy therefore ordered his men to abandon all artillery and wagons and to throw all remaining ammunition into the fort's cisterns. Each of Milroy's brigades prepared to abandon the fort the next morning, carrying with them only their small arms.

|

|

|

Composite panorama of Glen Burnie's pasture through which the 12th West Virginia advanced to the stone fence, at the treeline near what is now the water tower, and then retreated later in the day on June 14. |

~ Night Flight: June 15 ~

Milroy began the retreat at 1 a.m. To hasten his departure, he ordered all of the sick and wounded left behind in the various hospitals. Surgeons, medical orderlies, and nurses also stayed behind. Dr. Patton, still busy tending to the wounded, was one of those.

|

|

|

Abram's Creek circa 1989 |

Not knowing that Milroy was evacuating, the Confederate Gordon brooded over his orders to attack Main Fort at dawn. He was sure that he and many of his men would be killed. He remembered seeing the sun reflect off the Union bayonets and brass cannon in the fort the day before, and calculated his own chances for survival at one in a thousand. Agonizing over his imminent death, he wrote one last letter to his wife. He gave the letter to an aide with instructions to hand deliver it to his wife after his death. Just before dawn, Gordon took a deep breath, mounted his horse, spoke words of encouragement to his troops, crossed Abram's Creek and and began the long ascent up the hill leading to Main Fort.

“At every moment I expected the storm of shell and ball would end many a life, my own among them, “Gordon later admitted. “But on we swept, and into the fort, to find not a soldier there! It had been evacuated during the night.”

Milroy formed his retreat into two columns. The men were to take a route through a ravine north of town, across the Pughtown Road, U.S. 522, and northeast along the Martinsburg Road U.S. 11. “We felt that if we moved a wheel or made the least noise the enemy would fall upon us in overwhelming numbers,” Milroy later said. “We knew that our safely was in moving out quietly, leaving our wagons and artillery in their hands.” The front of the long retreating column got as far as 4½ miles along its route before it was spotted.

|

|

|

Taylor Hotel, used as a hospital

after |

Ten thousand Confederate — Johnson's division of Ewell's Corps — had spent the night on the eastern side of town. About 3 a.m. at Stephenson's Depot, Milroy's retreat and Johnson's patrols accidentally ran into each other. Intense fighting, heavier than that at any time during the previous two days, followed for about an hour. The 12th West Virginia, in the rear of the column, halted to await further orders. The troops heard the distant sound of signal gun from town, meaning that the Confederates had taken the town and were pursing from the rear. Milroy was desperate. Stampeding horses broke through the 12th's line adding to the confusion. Milroy ordered the 12th and other regiments to file left, away from the planned north-east route of escape. Somehow the 12th took the wrong road but got away. About 2,700 men, the 12th included, marched all day to Berkeley Springs, West Virginia, about 40 miles north of Winchester. After stopping to spend the night they forded the Potomac River at Hancock, Maryland, and marched further north to Everett, Pennsylvania. They arrived there on Friday, June 19th .

Milroy had his horse shot out from under him at Stephenson's Depot, but he safely took a different route of escape, northeast to Harpers Ferry with 300 of his men. Many others did not get away. They surrendered and were taken to Winchester as prisoners.

Union losses during the aborted night flight were staggering: 3,000 men were captured along with 23 cannons, 300 loaded wagons, more than 300 horses, and a large amount of food. Finally liberated, the townspeople rushed into the streets, shaking hands, shouting cheers, praising the soldiers, and listening to details of the battle while the gray-coats in turn listened to stories of the citizens' captivity. Outside the Taylor Hotel a band played, with the ladies of the town singing along, and the soldiers cheering the ladies. Inside the Taylor Hotel the scene was much different. Surgeons continued to treat the wounded; Alexander White, his leg gone, laid very still, his life slowly ebbing away.

~ Aftermath ~

Courthouse yard

where many Union POWs were held

All told, the lopsided three-day fight at Winchester cost the Confederates 269 men, including 47 killed, 219 wounded and three missing. The Union lost 4,443 men, with 95 killed, 348 wounded and 4,000 captured or missing. The 12th West Virginia alone lost 233, with six killed, and 36 wounded, and 191 captured. The Southern victory was, in the words of historian Wilbur S. Nye, “the zenith of [Ewell's] military career. In a single rapid offensive he had eliminated all opposition in the Valley, and had cleared the path for the passage of his own and two other corps into the north.” The Confederates used the victory as a springboard to invade Pennsylvania. Within two weeks the battle of Gettysburg would overshadow Winchester and all other battles of the war.

Several Confederate regiments stayed in Winchester to guard prisoners in the days following the battle. The yard of the Frederick County Courthouse, with its high iron fence, alone held 1,600 prisoners.

On June 18, three days after the battle, more than 3,300 prisoners able to walk were ordered to prisons in Richmond. Mrs. Lee, the diarist, walked beside the long blue column, observing that the soldiers were “driven like a flock of sheep…through the streets they had profaned by their presence & before the citizens whose lives they had made a burden… Some few of the most impudent of the Yankees ventured to call out that they would back down soon.”

Under heavy guard, the prisoners marched 95 miles south through the valley to the town of Staunton. They were then shipped by rail to Richmond, where many were held in a converted four-story tobacco warehouse — the city's infamous Libby Prison.

~ Dr. Patton's Imprisonment ~

|

|

|

Libby Prison |

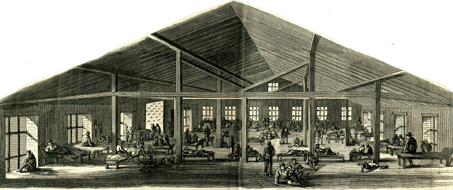

Dr. Patton was among the Union prisoners who were marched to Richmond, along with Lieut. Col. Northcott and Lieut. Henry F. Anshultz. Patton was held in Libby for five months. Forced to sleep on bare floors, in front of open windows, with insufficient clothing or blankets, he was exposed to cold temperatures, damp, and insects from the nearby James River. Sanitation was deplorable. The peaceful-looking sketch of prisoners at Libby, belies their suffering.

At first, Patton received a daily ration of a half-pound of beef, a pound of bread, and rice or beans, which he had to cook himself. But after only five months, the food largely had run out.

An entire day's ration in November 1863 consisted of an often-dirty sour cube of corn bread, three inches to a side, supplemented only by an occasional package of food sent by his friends from the 12th West Virginia.

Already of an apparently slight build, and under these inhumane conditions, Patton was stricken with severe muscle disease in the groin, abdomen and shoulders, from which he never fully recovered.

Lone water trough for Libby POWs

Patton's replacement in the 12th West Virginia was Dr. Alexander Neil, a native of Ohio and a graduate of the Cincinnati College of Medicine and Surgery. He wrote many letters home which later were published in a book. The regiment's historian, William Hewitt, once wrote that Neil was:

...somewhat of a wag. Moving slowly and cautiously along over the battlefield, as we did, he had ample time to pick up a skull, which he did. There was a round hole in it, just as such a musket ball would make, and it needed no telling that that was what made it. The command coming to a temporary halt, and assuming an air of solemnity, began a sort of mock lecture somewhat after the manner of a phrenologist. he said in substance about as follows: "Gentleman," said he," examining the bumps upon this cranium hastily, yet as carefully as circumstances will at present permit, assisted by the light of past and passing events, I think that I may say, with a confidence amounting to conviction, and that you will be justified in attempting my statement as an assured fact, that the original possessor of this poll was evidently of a more or less combative disposition. And gentlemen, judging from the light of current history, and the apparent time that this skull has lain where it was picked up, and the patent, convincing, ocular evidence sustaining me in the assertion, I have no doubt that the wearer of this cranium died of a gun shot wound." The boys within hearing smiled, some audibly, and as the march was resumed their arms and equipments felt less heavy on account of this display of waggishness.

|

|

Living conditions in Libby, where Dr. Patton spent days amid squalor and filth |

Patton was released in November 1863 along with 90 other Union surgeons, and he returned to his regiment, but he never fully recovered. After the war he served as a doctor in several towns in Western Pennsylvania, including West Newton and Smithfield. The

Uniontown (PA) Genius of Liberty reported in 1875 that Patton "was looking decidedly robust; judging from his appearance he

would tilt the scale beam at 230 pounds easily. Surely doctoring is a healthy business."

Site of Libby Prison

The Pattons produced six children -- Anna, Jessie, Ruth, Harry, Richard and George. Sadly, Anna died at the tender age of nine years, of diphtheria, in West Newton.

In 1884, Patton was appointed surgeon of the Central Branch, of the National Military Home, in Dayton, Ohio. He continued in good health, and the Dayton (OH) Journal once reported that he was "a man of giant frame. Among the veterans at the Home, with whom he was endeared almost as a lovable child, he was called the 'big doctor.' When he entered the [Army] he was small and very delicate, in singular contrast to his powerful frame in later years."

Patton attended the reunion of the 12th West Virginia at Wheeling in 1886. Recalled fellow veteran William Hewitt, Patton "paid the boys of the Twelfth the compliment why it was that there were so few West Virginia soldiers found in the Soldiers' Home at Dayton, and said that he replied to that question, that the boys of West Virginia were a self-reliant class of men, used to and feeling themselves fully capable of looking after and taking care of themselves during the war, and that he thought the same trait, characterizing them yet, of looking out for themselves, accounted for so few West Virginia soldiers being found in soldiers' homes."

|

|

|

Sprawling hospital at the soldiers home in Dayton |

|

|

|

Dayton Journal |

Over the years he could not walk long distances or get in or out of his buggy without pain and fatigue. At his death, Patton was eulogized by officials of the Military Home as having “unswerving fidelity and great ability, and endeared himself to all who knew him by the kindness of heart and gentleness in the sick room…It was the joy of [his] life to relieve the sufferings of the old veterans and make them in their declining years comparatively happy and contented.”

The Dayton Journal said he "was very popular with the veterans. He had their confidence in a professional capacity and was esteemed for his personal character and worth. When the news of his death spread about the camp with telegraphic speed, profound sorrow was everywhere manifest. In the city, too, where he was widely known and had scores of intimate friends, there was responsive sadness."

|

|

|

Grave in Dayton |

The doctor passed away at the Military Home on April 5, 1893, at the age of 53. He was buried in the cemetery on the grounds, and the funeral was attended by, among others, his uncle and mentor, Dr. Mathiot. The epitaph on his tall, prominent grave marker is a famed line from Shakespeare's Macbeth -- "After life's fitful fever he sleeps well." The Dayton Journal ran a lengthy obituary, and his old hometown newspaper, the Uniontown Genius of Liberty, published a shorter death notice.

He was survived by his wife Eliza and five children. At the time of Patton's death, their son Harry was employed by the Lake Shore Railroad at Goshen, Indiana, and their son Richard was attending the Michigan Military Academy at Orchard Lake, Michigan.

In 1997, Patton's pocketwatch, an 1877 gift from Absalom Fouch "in token of my esteem for him as a Gentleman and Physician," and crafted by jeweler W. Hunt of Uniontown, was found and purchased in an antique shop in San Ramon, California.

~ General Milroy's Final Years ~

Milroy in some ways got off much easier. He was relieved of command and brought before a Court of Inquiry to determine if he should face a court-martial for his poor performance. Letters he and colleagues wrote to President Abraham Lincoln, on Milroy's behalf, asking for leniency, are available for viewing today on the website of the Library of Congress' American Memory Project.

After six weeks of intense questioning, the board found Milroy innocent of any blame. President Lincoln, in reviewing the board's judgment, commented: “Serious blame is not necessarily due to any serious disaster, and I cannot say that in this case any of the officers are deserving of serious blame. No court-marital is deemed necessary or proper in this case.” Later in the war, Milroy briefly returned to action. He went on to a postwar career as a canal trustee and Indian agent.

|

|

|

Views of Milroy during the war |

~ Col. Klunk's Homecoming ~

|

|

|

Klunk's successor, |

The homesick Klunk of the 12th West Virginia finally got his wish. He resigned his commission again just a month after the battle, on July 12, 1863. The resignation was accepted in September.

Regimental historian William Hewitt noted that "Col. Klunk during the time the regiment was straggling about in the Cumberland Valley, sent in his resignation, upon the plea of sickness in his family, and while stationed at Martinsburg he received notice that it had been accepted. This left the regiment with Major [William B.] Curtis as the only field officer with it, Lieut. Col. Northcott being still a prisoner."

Klunk returned to his home, wife Margaret and children in Grafton, “broken in health and … suffering from intestinal trouble,” recalled his physician.

He suffered chronic diarrhea for the remaining 14 years of his life and died from its effects July 19, 1877, in Chillicothe, Ohio. His remains initially were buried at St. Margaret's Cemetery in Chillicothe, but later were relocated to Greenlawn Cemetery in Chillicothe, possibly in the military section. Margaret also is buried at Greenlaw.

Their son, John K. Klunk, got married at the age of 25 to 21 year-old Elizabeth O'Neil Campbell in Grafton in 1866.

Nothing more about this family is known.

~ The 12th West Virginia ~

The 12th West Virginia, under the new command of Col. Curtis, went on to other battles in the war and distinguished itself for bravery. It saw action in 1864 in Virginia at New Market, Winchester (again), Kernstown, Opequon, and Cedar Creek. The regiment's "desperate" valor at Fort Gregg near Petersburg in early April 1865 was cited specifically by Ulysses S. Grant in his best-seller Personal Memoirs.

At the Battle of New Market on May 15, 1864, several members of the 12th were captured by the Confederates, among them Samuel "Freeman" Younkin, Clark Gamble, James Newton Miller and William Stine. They were shipped to South Carolina, and placed with thousands of other POWs in the outdoor Andersonville Prison. Devoid of proper nutrition, sanitation and medical care, the POWs suffered from starvation, illness and in many cases death.

|

|

|

Hewitt's History of the 12th West Virginia |

The 12th was mustered out of service in June 1865. It counted 180 men dead during its three years of service. Fewer than one-third of the dead had been killed in action: 59 died in battle, 131 died of disease.

One of the women made a widow at the Winchester battle, Charlotte "Lottie" Bengough, traveled with her sister in law Celia Bengough to recover the body of her husband, Lt. John Bengough (sometimes spelled "Beugough"). Upon arriving, they obtained a pass from General Robert E. Lee's office to go "to the fortifications for the purpose of disinterring the body," she wrote, "and one to the hospital for a squad of our prisoners to rebury it in the cemetery. The General told us the body could not be shipped, as the railroad between Winchester and Martinsburg had been torn up. We buried the body in the cemetery and went to our boarding house."

While walking past one of the forts, the two Bengoughs noted "the Confederate flag floating proudly from its battlements." The hill on which the fort sat "was littered with the bodies of horses, mules, cannon balls and unexploded shells which had fallen on the soft hill side and lay in pockets made by the feet of the artillery horses in drawing Early's guns into position." Later they were arrested as spies, and held at Castle Thunder in Richmond, but eventually released in an exchange of prisoners. Lottie Bengough later married (?) McCaffrey and wrote a memoir of her saga that was published in the regiment's official history.

|

Author William Hewitt |

Some of the 12th 's survivors formed the “Twelfth West Virginia Infantry Association” and began holding reunions. One was held in Wheeling in 1886. At the gathering in 1889 in New Cumberland, the men asked William Hewitt to "compile a history of the Twelfth." He declined the request, but the following year, when Col. Curtis expressed his disappointment that nothing had been done, Hewitt reconsidered and agreed. He placed advertisements in local newspapers and wrote letters to former comrades asking for their memories in writing.

Hewitt completed the 226-page work in June 1892, and it was published under the title of History of the Twelfth W.Va. Infantry, The Part It Took in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. Click for the full text via Google Books.

Another member of the 12th, James Newton Miller, wrote of his experiences in the 47-page book The Story of Andersonville and Florence (Des Moines, Iowa: Welch, 1900).

Lt. Col. Robert S. Northcott, having been imprisoned at Libby, penned the article “Union View of the Exchange of Prisoners,” published in the 800-page Annals of the War Written By Participants North and South (Philadelphia: The Times Publishing Co., 1879).

[back to first page -- continued on next page]

|

Copyright © 1989-2013 Mark A. Miner |

|

Hotchkiss map image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Patton obituary courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society Archives/Library. Patton grave photograph by Michael J. Neely. All other images © Mark A. Miner or courtesy of the Minerd.com Archives. |