|

First Fight, First Blood (continued) |

|

|

|

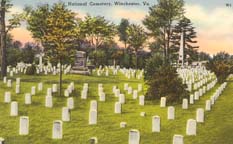

Entrance to Winchester's National Cemetery, and rows upon rows of headstones |

|

|

|

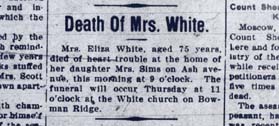

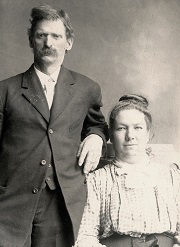

Widow Eliza White |

~ The Rest of Alexander White's Story ~

Alexander White lingered in his dying agony for four days after his wound. He finally died of complications from his amputation on June 18, three days after the battle ended. His body was most likely buried in a mass, unmarked grave, one of 2,338 unknown Union dead resting in the National Cemetery in Winchester. No marker identifies his burial site today.

Alexander's wife Eliza, is seen here. She is said to have often sat on the front porch of her home, watching the road in the desperate hope of a glimpse of her husband's return home. It took several months after his death for her to receive the news, most likely in a telegram or letter from West Virginia Adjutant General Francis P. Pierpont, a former member of the 12th West Virginia.

As a newly made widow, Eliza was left alone at the age of 35 to raise her four young children, two sons and two daughters, ranging in age from five to 12.

Eliza began to receive a soldier's pension from the federal government of $12 month. The original applications, affidavits and other supporting documents that she filled out to apply for the pension are still on file today at the National Archives in Washington, DC. The file has been examined personally by the author of this article, with a full set of copies made of each and every page.

|

|

|

Bowman Ridge Church, where Eliza rests |

After Alexander's death, his former landlord and brother in law, Josiah Simms, joined the Army. He enlisted on March 17, 1864, at Cameron, W.Va., as a member of the 1st West Virginia Infantry, Company D.

Just three months later, the Angel of Death stuck again, when Josiah was killed in action at the Battle of Piedmont, Virginia. Josiah left behind his second wife, Adaline (Cole) Simms; three sons from his first marriage to Sabina White (John, Charles and Samuel); and several children from the second marriage.

Marshall County records show that Eliza White purchased and lived on a 50-acre farm in Liberty Township from 1870 to 1892, and then lived with her various married children. She is said to have smoked a pipe for relaxation.

On July 12, 1905, at the age of 75, Eliza died in Moundsville at the home of her daughter Jane Sims, after 42 years as a Civil War widow. Eliza was laid to rest in an unmarked grave at the Bowman Ridge Cemetery near Silver Hill, WV. The church and cemetery are seen at right, circa 1997.

|

|

|

Ephraim Jackson book |

Her passing led to a short, two-sentence obituary in the Moundsville Daily Echo, under the headline, "Death of Mrs. White." Her grave apparently was never marked with any sort of headstone. A walk-through search by the author of this article, in 1997, proved fruitless.

Alexander and Eliza are mentioned in the book, Ephraim Jackson and Descendants: 1684-1960, authored and published privately in 1961 by Jesse Calvin Cross. (The title page and photograph of the author are seen at left.)

Unfortunately, and in error, Alexander's name is listed in the Ephraim Jackson book as "William Morgan White," even though Eliza's name is correctly given as "Eliza Mae White." The information was compiled for an entry on Alexander's son, William Morgan White, who had married into the Jackson family.

Alexander also is named in the chapter about the 12th West Virginia Infantry in the book History of Marshall County, From Forest to Field, authored by Scott Powell, and published in Moundsville in 1925. Original copies of both the Jackson and Marshall County books are now part of the permanent Minerd.com Archives.

The following spells out what became of Eliza's four children during their lifetimes.

|

|

|

Moundsville Daily Echo, 1905 |

|

|

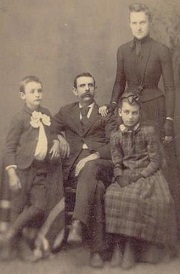

| James C. and Margaret Cain |

~ Daughter Margaret Ellen (White) Cain ~

As the eldest of Alexander and Eliza White's four children, Margaret Ellen White Cain (1851-1919) knew her father best, and was age 12 when he lost his life at war. She stayed at home with her mother for many years, assisting with housework and raising the younger three children.

When Margaret was age 24, and unmarried, she was sent to care for four young motherless children of James C. Cain (1847-1915), whose wife Rachel (Reed) Cain had died in 1875. (James was the son of John and Ann Elizabeth [Earlywine] Cain.)

Margaret must have taken a liking to the children's father, because she wed James less than two years later, on Jan. 11, 1880, and immediately became step-mother to the children -- Josephine Derrow, twins John Edwin and James Edward, and Ida Bell Antill. Margaret and James had five children of their own -- Osta Arminta Miner, Armena Viancy Miner-Marshall, Eliza Marshall, Susan J. Cain and Jessie Maude Cain.

The Cains resided on a hill above Bellton, Marshall County, where James labored as a farmer. Later, they moved to a log house at Rock Camp near Hundred, Wetzel County, where James "was largely engaged in handling coal," said the Moundsville Daily Echo. In 1907, after the untimely death of their unmarried daughter Susan, the Cains moved to a home on Addison Street in Washington, PA, to be near their married daughters Osta and Armena.

|

|

|

Margaret and James in older years |

In Washington, said the Daily Echo, James "was engaged at work with the Findlay Clay Pot Co. until about [1913] when he was compelled to give up factory work on account of poor health. During this period he has spent most of his time, when able to work, in garden making."

James passed away on Oct. 28, 1915, with his obituary carried in the Washington Observer and the Daily Echo in Moundsville.

Margaret outlived him by four years. She died of a stroke at age 67 on Jan. 6, 1919. They are buried together in Washington Cemetery.

Stories about Alexander White's fate were passed down through many family generations. A great-great-great grandson, author of this article, first heard them as a 10-year-old from his great-grandmother, Armena Cain Miner Marshall. In 1987, the author first visited Winchester, and in 1989 completed the writing of this article. In 2006, this webpage was created.

~ Son Benjamin Franklin "Frank" White ~

|

|

|

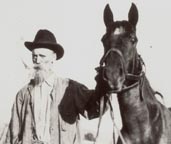

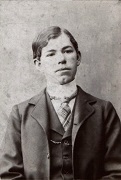

Frank White |

Age 10 at the time of his father's death, Benjamin Franklin White (1853-1919) moved away from West Virginia as a young adult.

He first went to St. Louis, where he had his photograph portrait tintype taken in 1880 (seen at right). He and his Swiss-born first wife (name unknown) lived in Kansas, where their sons George and Tom were born.

After the wife's untimely death at a young age, Frank returned to West Virginia, where he married Susan V. Williams (1881-1965), the daughter of Robert and Anna Williams, on July 24, 1901. Rev. James Craig officiated. At the time, he was age 48 and she 20, a different in age of 28 years.

|

|

|

Frank with a favorite horse |

The Whites made their home in Glen Easton, Marshall County and went on to have 10 more children -- Carrie Emerick, Robert White, Lovenia Allen, Viola Bremer, Florence Wesley Fordyce, Dorothy Fitch Toms, Gracie May Bedillion Moore Bartholomew, Lester Lawrence White, Clyde Wesley "Shorty" White and Clifford White.

Frank died at the age of 66 at Wellsburg, Brooke County, WV on Oct. 10, 1919, of "acute inflammatory rheumatism." His remains were sent by rail for burial at the Macedonia Church Cemetery on Pleasant Ridge near Silver Hill. (See burials list.) His official death certificate is available for viewing on the website of the West Virginia Division of Culture and History.

Susan outlived her husband by almost five decades. She passed away in 1865, and is buried at Salem Church Cemetery in Wetzel County, WV.

Frank's son Tom (1889- ? ), from the first marriage, served in the U.S. Army in World War I, and in 1978, some 61 years later, received a medal for bravery during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The award was featured in an article in the Akron (OH) Beacon Journal on Nov. 12, 1978.

Frank's son Clyde "Shorty" White (1920-1990), from the second marriage, was a veteran of the Pacific Theatre in World War II, and was a real estate broker and insurance agent who owned the White-Jones Agency for four decades in Wooster, Ohio.

|

|

|

Frank's son Lester "Red" White at a 1996 reunion -- the last surviving grandson of Alexander and Eliza White |

|

|

|

Will and Viola White |

~ Son William Morgan White ~

Son William Morgan White (1856-1938) was age seven when his father was killed at war.

He married Viola Jackson (1872-1940) of Wetzel County, the daughter of Joseph Martin and Charlotte (Banning) Jackson. Their wedding took place on Sept. 15, 1889, at the home of John Scearse, by the hand of Rev. G.W. Franklin. Will was age 33, and Viola 17, at the time of marriage. Because she was legally underage, Oscar Jackson provided his consent to the union.

Viola was about nine inches taller than her husband, as she had an exceptionally large build -- she was about 6 ft., 2 in., while he stood about 5 ft., 5 in.

The Whites lived on a farm of 54 acres at a point of land on the Silver Hill side of Macedonia Church.

They had three children -- Velma Orlena Pyles, Cecil Truman "Butch" White and Winona Mae Chambers.

|

|

|

Macedonia school, where Velma Pyles taught |

Will was superstitious, and never burned locust wood, or wood that had been hit by lightning. He and Viola were active in the supporting U.S. troops during World War I by knitting American flags and other wearing apparel. Viola began to lose her health in 1919 when she suffered several strokes. She lived another 21 years despite additional strokes.

Will died in 1938, and Viola followed him in death in 1940.

Daughter Velma White (1892- ? ) was born in 1892 in Silver Hill. She married Perry Pyles (1892-1947), son of Calvin and Flora Pyles. They were joined in matrimony on Christmas Day 1914, in Wheeling, Ohio County, by Rev. W.S. Dysinger. Velma taught at the one-room Macedonia School, having taken a test at age 18 upon finishing high school. She died in childbirth after suffering with convulsions. Perry married again, to Clara Sellers, resided in Cameron, Marshall County, and died on Nov. 17, 1947.

Son Cecil Truman "Butch" White (1906- ? ) was born in about 1906 in Silver Hill. He married Georgia Clara Miller (1912- ? ) of Wetzel County. They were wed on Oct. 19, 1934 by Rev. Grover J. Johnson in Middlebourne, Tyler County, WV. She was the daughter of C.W. and Chloa (Stern) Miller. Butch was age 28, and Georgia 22, at the time. They raised a family in the Silver Hill area. They rest for eternity in the Macedonia Church Cemetery. In the early and mid-1990s, Butch's son Harold "Bob" White hosted White-Chambers reunions. In October 1997, the Tri-County Researcher newsletter, published by Linda Goddard Stout, printed inscriptions from Viola's old family Bible.

|

|

|

Will and Viola White, at home, Silver Hill, 30 years apart -- 1905 and 1935 |

|

|

| Jennie Sims |

~ Daughter Ruth Jane "Jennie" (White) Sims ~

Daughter Ruth Jane "Jennie" White Sims (1858-1935) was age five when her father died, and she likely had little or no memory of him.

She married Civil War veteran Newton Gilbert Sims in 1881, when she was 23. They were wed in the same year he completed a 14˝ year prison sentence for murder. During the war, Newton had served with the 9th West Virginia Infantry.

They had two children -- William Alexander Sims and Bernice Horner.

|

|

|

Jennie and Newton and children |

The Simses resided in Moundsville, WV, but separated, and eventually divorced in October 1902. Jennie moved to Washington, PA in about 1910, where she resided at 875 Addison Street.

Later, she married Andrew D. Walker, but eventually retook her "Sims" surname.

Her former husband Sims died in 1919 in Calhoun County, WV, and is buried at Carpenter Cemetery near Orma, WV.

In the 1930s, Jennie's family apparently enjoyed attending one or more of the annual Cain-Jackson Reunions in Mannington, WV. The events were organized by Enos Perry Jackson, who served as president from 1925 to 1942. There always were questions as to whether the Jacksons were related to famed Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, but according to the book, The Jackson Family, published in 1961 by Jesse Calvin Cross, there was no family connection.

Jennie died at the age of 77 at Washington Hospital, on Dec. 1, 1935, after suffering from chronic nephritis. The funeral was held nearby at the home of her niece, Armena (Cain) Miner Marshall, at 750 Fayette Street. She was laid to rest in Washington Cemetery.

Jennie's great-granddaughter Carol Lanza has developed a genealogy website of the White and Sims families, among others, and a page transcribing some of Alexander White's Civil War pension records.

Jennie's son William Alexander Sims (1882-1965 ) was born on March 13, 1882 in West Virginia, presumably Marshall County. As a young adult, he resided in Moundsville. On June 26, 1909, when he was age 27, William married 29-year-old Harriet Ethel "Hattie" Gantz (1880-1959). The wedding was conducted in Fairmont, Marion County, WV, by Rev. L.K. Probst of the Lutheran church. Their two children were Mildred Elizabeth Sims and William Harold Sims. The family resided in or near Upper Sandusky, Wyandotte County, OH. Ethel passed into eternity on Dec. 9, 1959 in Sycamore, OH. William died in Upper Sandusky on March 14, 1965, with interment in the North Salem Lutheran Church Cemetery.

|

|

|

William Sims and Bernice Sims Horner |

Jennie's daughter Bernice E. Sims (1883-1943) was born on Nov. 4, 1883 in Marshall County. At the age of 32, on Nov. 4, 1915, she married 34-year-old Melvin Edward Horner (1881-1965), son of Obadiah Marshall and Arra Bell (Baker) Horner. The ceremony was held in the Jefferson Avenue United Methodist Church in Washington, by the hand of Rev. Grafton T. Reynolds. They had three children -- Bernard Alvin Horner, Thelma Gertrude Horner and Ellis Marian Horner. Bernice died in Claysville on July 26, 1943, at the age of 60, and was laid to rest in the Claysville Cemetery. Melvin survived her by more than two decades. He passed away in Washington Hospital on July 30, 1965.

~ Legacy of the Battle ~

The Second Battle of Winchester, as a minor conflict in the overall Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania, has been little noted over the years. The most comprehensive coverage of the battle was the book, The Second Battle of Winchester, by Charles S. Grunder and Brandon H. Beck (1989). It also has been featured in articles in Civil War Times (1976) and America's Civil War magazine (1997), and various booklets published by local authors in Winchester.

As for the town of Winchester, the June 1863 battle was just one of 72 times the town changed hands during the Civil War. During the years since the war's end, many of the visible remnants of the battle have vanished. Main Fort became the Whittier Acres subdivision. West Fort became the property of Burrell Luttrell, who built a house in the center of it.

The Taylor Hotel remained a fixture in the center of town for many years. On June 6, 1913, almost to the day of the 50th anniversary of the battle, a Confederate Memorial Parade was held, with with cadets from the Shenandoah Valley Academy marching past the hotel and throngs of spectators. The building was converted into a department store and purchased by the McCrory chain. Its walls still stand today even though the building is vacant and no longer used by McCrory.

|

|

|

Stately Taylor Hotel -- with its distinctive second and third story colonial columns -- as seen in the 1920s |

|

|

|

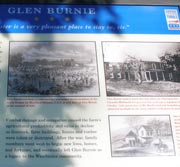

Tourist panel at Glen Burnie |

In 1970, when the John Kerr Elementary School was being built nearby, the Glen Burnie stone fence was bulldozed down because of its very poor and dangerous condition. It was replaced with a chain link fence. Even then, as it had for many years, the fence line marked the southern border of a pasture, where cows lazily grazed, unaware of the violence there in the hot war-torn summer of 1863.

The battle's legacy gained prominence in 1989 upon publication of the book, The Second Battle of Winchester, authored by Charles S. Grunder and Brandon H. Beck. The volume was part of the Virginia Civil War Battles and Leaders series. The 12th West Virginia and Col. Klunk are named thrice in the book, but with no mention of Glen Burnie.

In the spring of 1990, publication of this article generated stories in the Pittsburgh Press, North Hills (PA) News-Record and in the Stray Shots newsletter of the Western Pennsylvania Civil War Round Table. The author made a slide presentation before the Round Table in Sewickley, Pa on Feb. 20, 1991, using his own research images as well as color photos lent by Dr. Beck.

A book published in 2003 by the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, The Gardens of Glen Burnie, acknowledges that the battle took place on the property. "Records indicate that Glen Burnie's livestock, farm buildings, fences and timber were taken or destroyed during the War's battles and encampments," writes author Marge Lee on page 9. "Even Glen Burnie's lawn fell victim..."

Opened in the spring of 2005, the museum stands just a few hundred yards from where Alexander White fell with his mortal wound. The museum tells the story of the art, history and culture of the great valley for which it is named, together with the nearby Glen Burnie Historic House and Gardens, which was a silent witness to the Civil War battle. The $20 million museum has three levels that explore the sweep of Shenandoah Valley history and display collections of decorate arts amassed by Glen Burnie's former owner, Julian Wood Glass Jr. The museum also features a gallery of miniature houses and rooms collected by the late R. Lee Taylor, who assisted the author of this article during a visit in October 1989. The museum complex is located at 901 Amherst Street in Winchester.

|

|

|

Museum of the Shenandoah, on the Glen Burnie estate and battlefield site |

|

| Beleaguered Winchester |

In 2002 and 2007, when great-great-great-great grandsons of the soldier’s were born, they were named in his honor -- Jordan Alexander Miner and Logan Alexander Foster.

In June 2007, a new book authored by Richard R. Duncan and issued by the Louisiana State University Press, is published and includes a reference to this article in the bibliography. Entitled Beleaguered Winchester, the book is found in bookstores including at Harper's Ferry National Historic Site. According to the publisher's website, "During the Civil War, the strategically located town of Winchester, Virginia, suffered from the constant turmoil of military campaigning perhaps more than any other town. Occupied dozens of times by alternating Union and Confederate forces, Winchester suffered through three major battles, including some seventy smaller skirmishes. In his voluminous community study of the town over the course of four tumultuous years, Richard R. Duncan shows that in many ways Winchester's history provides a paradigm of the changing nature of the war. Indeed, Duncan reveals how the town offers a microcosm of the war: slavery collapsed, women assumed control in the absence of men, and civilians vied for authority alongside an assortment of revolving military commanders."

|

|

|

Alexander Neil and the Last Shenandoah Valley Campaign |

This is Duncan's second book involving the 12h West Virginia Infantry. His earlier book, published in 1996 by White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., is entitled Alexander Neil and the Last Shenandoah Valley Campaign: Letters of an Army Surgeon to His Family, 1864. It chronicles the wartime experiences of Dr. Neil, who replaced Dr. Patton after the Winchester battle.

~ Bibliography ~

Second Battle at Winchester

Cartmell, T.K. Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants. N.P., 1908.

Davis, Maj. George B., Leslie J. Perry and Joseph W. Kirkley. The Official Military Atlas of the Civil War. New York: Fairfax Press, 1983.

Early, Lt. Gen. Jubal Anderson. Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1912.

Freeman, Douglas Southall. Lee's Lieutenants. Vol III: Gettysburg to Appomattox. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1945.

Gordon, Gen. John B. Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1903.

Grunder, Charles S., and Brandon H. Beck. The Second Battle of Winchester. Lynchburg, Va.: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1989.

Lee, Marge. The Gardens of Glen Burnie. Winchester, Va.: Museum of the Shenandoah Valley. 2003.

Lee, Mrs. Hugh H. Diary, Typescript. Handley Library, Winchester, Va.

Longacre, Edward G. “Target: Winchester, Virginia.” Civil War Times, June 1976.

Mathews, William C. Letter. Central Georgian, July 9, 1863. Microfilm copy, University of Georgia Library, Athens, Ga.

McDonald, Cornelia. A Diary with Reminiscences of the War and Refugee Life. Nashville: Cullom & Gertner Co., 1934.

Nichols, G. W. A Soldier's Story of His Regiment. Jessup, Ga.: 1898.

Nye, Wilbur Sturtevant. Here Come the Rebels. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965.

Quarles, Garland R. The Story of One Hundred Old Homes in Winchester, Virginia. Winchester: 1967.

Winchester-Frederick County Civil War Centennial Commission. Civil War Battles in Winchester and Frederick County, Virginia, 1861-65. Winchester, Va.: reprint, 1971.

Twelfth West Virginia Volunteer Infantry

Company, Field and Staff Muster Rolls. 12th West Virginia Volunteer Infantry. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Hewitt, William. History of the Twelfth Regiment. Steubenville, Ohio: H.C. Cook & Co., 1892.

Lang, Theodore F. Loyal West Virginia. Baltimore: Deutsch Publishing, 1895.

Military Service and Pension Records. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Miller, James N. The Story of Andersonville and Florence. Des Moines: Welch, 1900.

Moore, Frank, ed. Rebellion Record, 1863. Vol. 7. New York: G.P. Putnam, H. Holt, 1864.

National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Annual Report of the Central Branch for the Year Ending June 30, 1893: General Orders, No. 57, Central Branch, 1893; Proceedings of the Board of Managers, 1884 and 1893.

Neil, Alexander. Letters to His Parents. Alexander Neil Collection (#6120), Manuscripts Division, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Northcott, Lt. Col. Robert S. “Union View of the Exchange of Prisoners.” Annals of the War. Philadelphia: The Times Publishing Co., 1879.

Powell, Scott. History of Marshall County, W.Va. Moundsville, W.Va.: 1925.

State of West Virginia. Adjutant General's Report. Year Ending Dec. 31, 1864.

U.S. War Department. War of the Rebellion. Series 1, Volume 27. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1891.

General Civil War Background

Boatner, Mark Mayo III. The Civil War Dictionary. New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1959.

Catton, Bruce. The Coming Fury. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1961.

Hesseltine, William B. Civil War Prisons. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 1930; reprint, New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1964.

Lord, Dr. Francis A. They Fought for the Union. Harrisburg, Pa.: The Stackpole Co., 1960.

Randall, J.G., and David Herbert Donald. The Civil War and Reconstruction. 2nd ed. 1937; reprint, Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Health and Co., 1969.

[back to first page -- back to second page]

|

Copyright © 1989-2013 Mark A. Miner |

|

Eliza White obituary courtesy of the Moundsville (WV) Public Library. Vintage White family photographs courtesy of Harold R. White, Phyllis White Landis and Carol Taylor Lanza. All other images © Mark A. Miner or courtesy of the Minerd.com Archives. |