| Home |

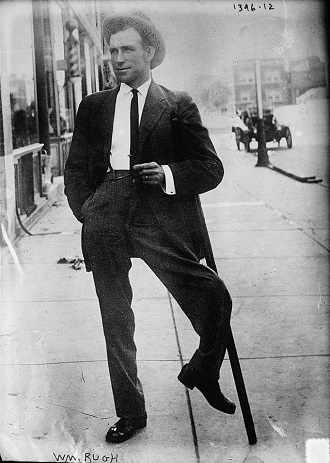

| Photo of the Month May 2021 |

|

| See Previous Photos Unknown Faces and Places | |

|

|

|

Billy Rugh's grave marker is inscribed with this verse of scripture from the Book of John: "Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends." His inspiring life followed by a heroic death plunged the city of Gary, IN into mourning and -- unheard of -- shut down its steel mills for an entire day.

William Arthur Rugh was born near Moline, IL, the son of William Oregon and Henrietta (Glenn) Rugh and stepson of Margaret Ann (Emerick) Baxter Rugh of the family of Iowa pioneers Emanuel and Elizabeth (Boderfield) Emerick. As an infant he lost use of his left leg and for the 40 ensuing years of his life he considered it a useless appendage. He migrated in adulthood to Gary, where he worked at the age of 40 as a newsboy, selling newspapers every day on the block between at Sixth Avenue and Broadway.

In the fall of 1912, he learned that Ethel Smith, a teenage woman whom he did not know, had been badly burned in a motorcycle gasoline explosion. She faced certain death unless receiving a substantial graft of skin. It did not take Billy long to decide that his bum leg could be used for this purpose and invited surgeons at Gary General Hospital to perform an amputation. At first they declined, but when word became public, the hospital relented when the community was overwhelming in its support. Said the Chicago Tribune, "he has received $600 in money, a free life insurance, offers of enough artificial limbs to supply a centiped, and felicitations from all parts of the country." Citizens of Gary nominated him to receive a Carnegie Medal from the Carnegie Hero Fund. Local women athletes organized an indoor benefit baseball game. Newspapers across the country voiced their support. One, the Pittsburgh Press, wrote this in an editorial.

When we come to think of it, Mr. William Rugh, you are not only a hero but you are also a gentleman. In the exclusive homes of the West End, London; of Fifth ave., New York, and of the aristocratic quarters of our own city of Pittsburg, there are many carefully nurtured and expensively "educated" and elegantly attired claimants to that latter title who are not capable of such gallantry as that shown by your offer. With all their advantages of ball-rooms and drawing-rooms, you are their superior in manners.

"I can't understand it," he said to a newspaperman. "Why are people so good to me?" The surgery went forward and was successful. But while 160 square inches of skin were taken from his removed leg, and grafted to Miss Smith, a recovery was not to be. The stump began to heal, but his lungs and bronchial passage became infected with pneumonia. And on Oct. 18, 1912, just 15 days after his surgery, he died. His final words, said the Moline Dispatch, were "Guess I'm some good -- after all." As the news of his passing became known, Gary's Mayor Thomas Knotts appointed a committee to look into the possibility of commissioning a statue. A wreath was placed along the street where he once hustled to sell papers. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported that "for the first time in their history the steel mills of Gary will be idle to-morrow. All stores will be closed. There will be no crowds in the theaters and concert halls. In every church there will be said a prayer for the soul of a crippled newsboy. Every minister will speak of the city's greatest deed of heroism. Thousands of people will try to catch a last glimpse of the face of the man who had died with a happy smile on his lips..."

Honorary pallbearers included Gary's mayor, the president of the Gary Commercial Club, general superintendent of Illinois Steel Company, general manager of the American Bridge Company, general manager of American Sheet and Tinplate Company, president of the YMCA of Gary, superintendent of schools in Gary, a banker and the commander of the Knights Templar. The cortege to the cemetery was a mile long. More>>>

|

Copyright © 2021 Mark A. Miner |