|

Henry

Hinerman |

Windy Gap Church Cemetery |

Henry Hinerman -- a.k.a. "Hineman" -- was born on Aug. 24, 1844 in Greene County, the son of Thomas and Elizabeth (Bush) Hinerman. He never married and sacrificed his life for the Union cause during the Civil War.

A midwife assisted in Henry's birth, with the father also present. At his birth, Henry's name and date was inscribed in the family Bible, published in 1840 by D. Fanshaw of the American Bible Society, New York.

Henry grew up on his parents' 100-acre farm in Aleppo Township and helped them with farm labor, including plowing their wheat field. Their post office circa 1860 was Cameron, WV, although they lived over the border in Pennsylvania. Friends considered him a sound, able-bodied young man and industrious in his work.

Henry was eager to play his part during the Civil War. At the age of 17, in 1862, intending to enlist, he left home with friend Lewis Parry and traveled to a recruiting station in the county seat of Waynesburg. His horrified father came after him, and took him home because he was not of legal age.

He did not wait long at home before departing again. After reaching is 18th birthday in late August, he officially enlisted at Waynesburg on Sept. 4, 1862 .

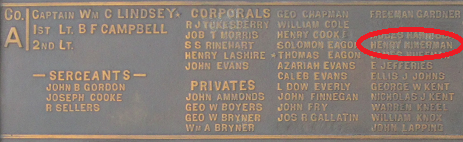

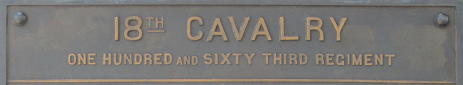

Henry was placed within the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Company A. His company was commanded by William C. Lindsey. Among the other privates in the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry were John Finnegan, John McKean and Henry C. Ullom, each of whom is profiled on this website. The regiment's story is told in detail in the 1909 book History of the Eighteenth Regiment of Cavalry, Pennsylvania Volunteers, authored by by Theophilus Francis Rodenbough and Thomas J. Grier.

|

18th Pennsylvania Cavalry battle flag |

From Waynesburg, the regiment traveled to Pittsburgh where it drilled at Camp Howe. From there it was sent in December to Badensburg, near Washington, DC, where the men received carbines and sabers and took basic training. Then on the first day of 1863, they were ordered into Virginia and stopped on "the Virginia end of the Long Bridge over the Potomac, and a fortnight later to Germantown, two miles from Fairfax Court House, on the Little River Turnpike," wrote Rodenbough and Grief. They were to spend the winter at Fairfax Court House, guarding the District of Columbia against enemy advances. Their quarters were rough cabins made of logs with wooden chimneys and walls plastered with mud.

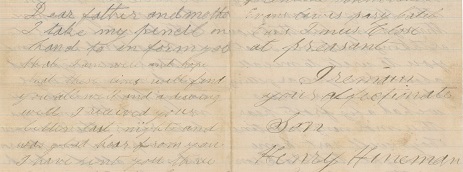

As he was paid, Henry sent money home to his parents, enclosed with letters. In one of his first letters from Camp Howe, near Pittsburgh, dated Sept. 25, 1862, he wrote:

Dear father and mother,

I take my pencil in hand to inform you that I am well and hope that these lines will find you all well and a doing well. I received your letter last night and was glad hear from you. I have sent you three letters, two by mail and one by patrick grifin. I sent you 10 dolars in money and 30 in a treasury order. I want you to see to it and get the money and pay of as much deat as you can. We have not got our uniforms yet but the Captain seys we will get them in the morning. We have lotts to eat such as it is bread and meat and potatoes, rice, sugar and a good many things. camp how is about 4 miles up the monongahela river. there is now in camp about one thousand men all of which is cavalry except us. We have had a right smart of trouble in our company as Cornel Smith wants to split our company and poot us in ould regiments but our oficers say that they will take us back home before they will due that. While am writing the thougt runs through my hed that you are are talking about me. I wat you to write to me all about how you ar getting along with your tobaco. We had a big frost hear this morning. Martins boys will sart home to night. Tell Jackson and thomas that I want them to be good boys and dew all that there mother tells them. I want mother to not grieve about me eny more. tha see can help when I hear of hit. it maks mee feel bad. I am with Josep Golentine, John Evans, A. Evans, lewis pary, Caleb Eans. I mus Close at preasant. I remain your affectionate Son.

|

Above and below, fragments of two of Henry's letters home. National Archives. |

|

Most of the 18th Cavalry's time was spent scouting the countryside. In unfamiliar terrain and with minimal weapons training, there was not much the men could do if encountering rebels. At times they were caught in surprise ambushes with some of the men captured. Once the 18th Cavalry brought in 28 Confederate prisoners. Rodenbough and Grief wrote that these skirmishes were "in the nature of a dress rehearsal. The men were being hammered into shape for the more important conflicts pending...."

Henry was on duty as a picket at Chantilly near Fairfax, VA, from Feb. 10-26. On Feb. 25, the 18th Cavalry was attacked by the 43rd Virginia Cavalry -- known as Mosby's Raiders -- fighting under the command of Col. John S. Mosby. He was shot and wounded, the bullet entering "the fleshy part of the left arm, the ball entering left side passing just between the rim of the stomach and the skin," recalled friend Parry. It came to rest "about ten inches from the place where it entered."

The wounded Henry was taken prisoner in the action. He was held only a short time before being exchanged and then sent to the 18th Cavalry's regimental hospital. Then on March 10, he was ordered to receive additional treatment to St. Aloysius General Hospital in the District of Columbia.

|

Above: 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry officers in camp near Fairfax Court House. Below: Adams Express delivers soldier packages from home. |

|

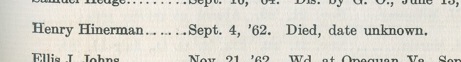

While in the Washington hospital, he wrote to his parents on April 7, 1863:

Dear father and mother,

I take my pen in hand to in form you that i am as well as usual and i hope that these few lines will find you all well and a doing well. i received your letter yesterday of the 1 of this month and was glad that you was all well. well i was out yesterday and sean our major and two of the captains and i got at them to try and get my pay and they they [sic] did try and got mee five monts...

|

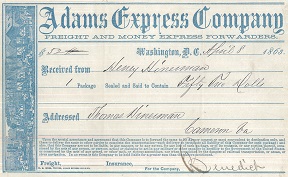

| Receipt for money which Henry

sent home

in 1863. Three months later he was dead. National Archives. |

...sack and my canteen and my fittings (?) on my hat. Well i have tryed to get home but it seems all in vane as the doctors here dont care a cant for a fellow and i no that it is hard for you when myou want to see me and cant get to. Well I had one egg for easter. you said that mother had kept the the turkey. Well you need not a done that. Well i must close for the preasant time yours truly.

On April 8, having received his back pay, Henry sent $52 to his parents, couriered by Adams Express.

He recovered sufficiently over a span of two months and was sent back to his regiment on May 22, 1863, finding them at Fairfax Court House, VA. Friend Parry observed "that inflammation had set in where the ball had passed through. it was black and blue clear across & I think about 4 or 5 inches in width."

Within a few days after rejoining his unit, the men were ordered to ride into Pennsylvania. At that time, General Robert E. Lee was leading more than 70,000 infantry and cavalry in an invasion through Maryland and Pennsylvania in an effort to collect food and clothing supplies as well as capture the latter's state capitol in Harrisburg. It all culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1-3.

On June 30, Henry and the 18th Cavalry were in Hanover, PA, protecting the rear of General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick's troops. As they halted in the streets of the towns, the Union men were attacked by a column of enemy cavalry commanded by General Jeb Stuart. While in chaos at first, the 18th Cavalry rallied and made a counter-charge in town, helping force the enemy to withdraw. In that fight, Henry's regiment lost three men killed, 24 wounded and 57 missing, who likely were taken prisoner.

|

|

Henry Hinerman's name on the Pennsylvania Monument at Gettysburg. Below, the monument to the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry on the battlefield. |

|

Monument to the Hanover battle |

Henry was one who was captured. The rebel army force-marched him and his fellow POWs for 20 miles during the night to Dover. As they were not equipped to accommodate prisoners over long distances, the Confederates arranged to swap prisoners with the Union the next day. The bedraggled men then were sent to a Union parole camp in West Chester, PA.

On July 1-3, 1863, with Henry out of commission, the 18th Cavalry took part in the nearby Gettysburg fight, at the very southern tip of the battlefield near Big Round Top. The regiment was part of what scholars have called a "suicidal attack" led by Gen. Elon Farnsworth.

Under heavy fire, the 18th retreated. Although he was away at the time of battle, Henry's name today is memorialized on the 18th Cavalry plaque on the famed Pennsylvania Monument at Gettysburg.

About the time of the Hanover battle and capture, Henry contracted typhoid fever. Once back with his cavalry unit, he was so sick and in pain that he requested a leave of absence. Parry wrote that "he complained about it hurting him till he became delerous."

He and Parry then traveled home together, arriving July 6. Army records, however, suggest that the leave may not have been officially sanctioned and that he was considered "absent ... or deserted."

Wrote Parry, "he was very bad from next day after he got home till he died."

Henry was treated by family physician Dr. S.B. Stidger but was beyond recovery. The wounded region of his abdomen remained blue in color. Friend Parry came every day or two to visit, but he could see that the prognosis was not good.

Nine days after returning, Henry died in his parents' residence on July 15, 1863, at the age of 18 years, 10 months and 21 days. Charles Stewart was present at death, and Parry helped prepare the body for burial.

Thomas' remains were laid to rest in Windy Gap Cemetery. A stone was erected at the grave, reading:

HENRY HINEMAN Son of Thomas & Died in the Service 15th 1863 Aged 18 Years, |

His grieving parents petitioned the federal government for a military pension as compensation for their loss. Under the spelling "Hineman," the mother's pension was awarded in 1881 [Mother's App. #281.998 - Cert. #243.386]. She thus began receiving monthly checks in the amount of $12 each.

After the mother died in 1891, the widowed father then applied to receive the pension, but it was not granted. [Father's App. #549.718]

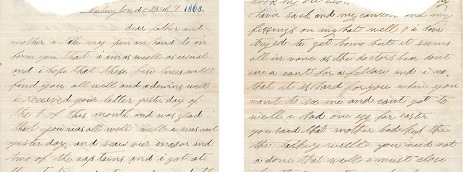

In 1909, Henry was named on several pages of a book about his Civil War regiment, History of the Eighteenth Regiment of Cavalry, Pennsylvania Volunteers, authored by by Theophilus Francis Rodenbough and Thomas J. Grier. In this record, the official cause of his death was shown as "disease."

|

Henry's entry in the official history of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry |

Copyright © 2014, 2017-2019 Mark A. Miner