|

|

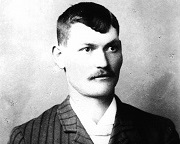

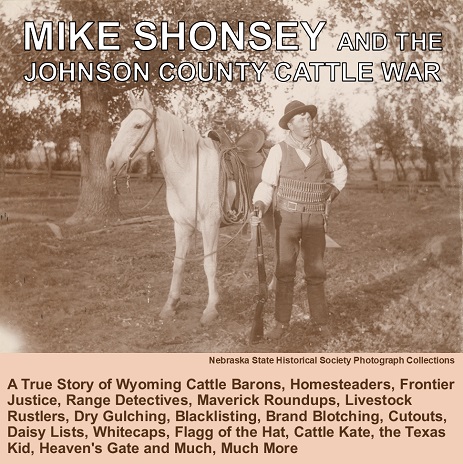

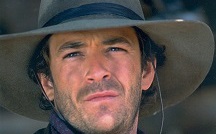

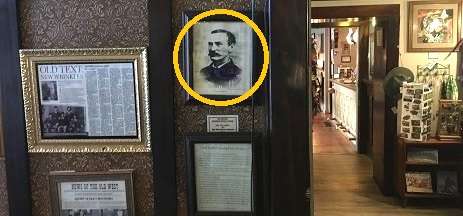

Mike Shonsey - Nebraska State Historical Society |

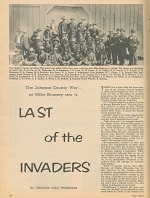

Two decades later, the Hallmark Channel’s Johnson County War, starring Burt Reynolds, Tom Berenger and Rachel Ward, aired on television at a lesser but still overlong 4:00 hours.

The human dramas of the War, pitting wealthy cattle-owners and their hired Texas gunmen against common ranchers and rustlers, are rife with twists, turns and entanglements. The events even swept into its fold our newlywed cousins Mike and Olive (Sisler) Shonsey, on the owners’ side of the animosity.

The storyline went on to inspire a host of other expressions in American popular culture. And it wasn’t a “war” at all, actually, but rather an ambitious assassination raid that failed in planning and execution.

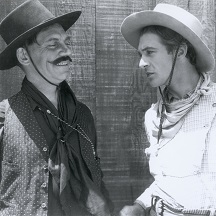

Among the other better-known pop culture versions are the 1940s novel Shane by Jack Schaefer, later made into a popular film starring Alan Ladd Sr, and spoofed in episodes of television’s Batman in the 1960s with Cliff Robertson portraying the villain “Shame.” Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian, said to have been the prototype for the modern western, was adapted into a film with Gary Cooper followed by a television series loosely based on the original. Another version was The Invasion of Johnson County starring Bill Bixby and Bo Hopkins. A small library of books has been published on the topic.

This article tries to simplify a highly complicated set of facts and opinions with the sharp plot twists and widely differing, complex and conflicting personalities. The words of the observers and authors who knew the story best are used throughout to bring us as close to the clarity of reality as possible.

The newlywed Shonseys, who were married in 1891 in Nebraska, a year before the raid, had settled in Wyoming for his employment. He was well known as a stock inspector and ranch foreman working for large cattle owners. Mike’s job as a hired man evolved into roles of scouting/espionage, planner and shootist in the War on the side of his employers.

The first year-and-a-half of marriage for the young couple, in the big sky grasslands of Wyoming’s Powder River, was unlike anything most couples ever endure or survive. What they experienced, said one writer, was a “tragic and bizarre” set of circumstances that “split the young state from scalp to toenails.”

|

| Among films depicting elements of the Johnson County War have been, clockwise from upper left, The Virginian (Walter Huston and Gary Cooper, University City Studios), The Invasion of Johnson County (Bo Hopkins and Bill Bixby, Disney Channel) and Shane (Alan Ladd Sr. and Jack Palance, Paramount Pictures) |

|

Before the so-called War ceased, Mike was alternately branded as a range detective, brand blotcher, spy, invader, gunman, indicted murderer, exonerated prisoner, self-admitted killer and finally a free man. Olive herself makes a handful of appearances in the history books, including one fictional account.

Their thoughts on the matter largely are a mystery. Olive died young, after 14 years together, and Mike was stone-cold silent until his later years when he became the sole survivor, the last man standing.

Ironically, at the end of his life more than half a century after the fact, Mike was considered one of the most respected feed growers and cattle owners in the greater region. Was he a devil? Or in the right? Or, like an onion, a deeply layered combination of both?

|

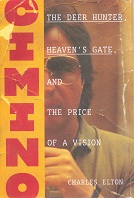

| Heaven's Gate, directed by Oscar-winner Michael Cimino, is the best known film treatment of the War, despite its disastrous box office reception - United Artists |

|

~ Roots of Conflict ~

When the Shonseys began their married lives together, the West increasingly had become engrained in the popular American imagination as a place of danger, risk and reward. General Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn in 1876, the killings of Crazy Horse at Fort Robinson and Sitting Bull at Standing Rock, and the mass shooting of Lakotas by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee in 1890, only reinforced that image to an audience in the East and in Europe.

The root of the War was the economics of the cattle business followed by a strain between cattle owners and ranchers in the community of Buffalo in the County of Johnson, Wyoming. The “have’s and have not’s” relationship of this tension, and who was right and who was not, remains at the root of public interest today.

|

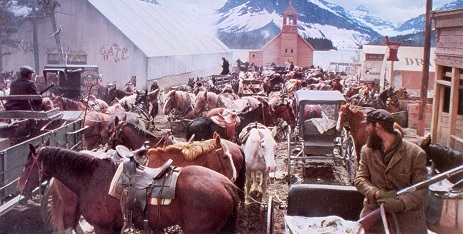

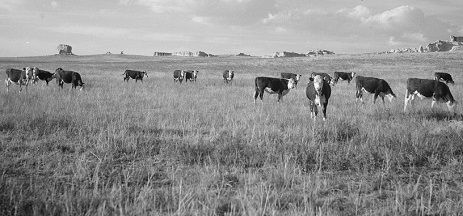

| Wyoming cattle, at the heart of the Johnson County War |

|

Fred Hesse Malcolm Campbell, Sheriff |

Both sides ended up outside the law, both sides were wrong, and a few of us on both sides have had to stand by while hundreds of people who knew and know next to nothing about it casually tell the world what was right and who was wrong… Now, all these years later, the question still remains. If two antagonistic individuals stand up and scream “LIAR” at each other for long enough, who in the end is proven to be the liar.

Robert B. David, in his book Malcolm Campbell Sheriff, says that “For years the story of the raid was whispered up and down the range, becoming more and more garbled and untrue at every telling until by now there is little substance that is known that has much foundation of proof.”

James Mitchell Clarke, in his foreword to Asa S. Mercer’s book Banditti of the Plains, calls the entire matter “the crime of the ages.” Mercer himself writes that “The invasion of the state of Wyoming by a band of cutthroats and hired assassins… was the crowning infamy of the ages. Nothing so cold-blooded, so brutal, so bold and yet so cowardly was ever before recorded in the annals of the world’s history.”

~ Rustling and Thieving and Cattle Economics ~

In 1890, Wyoming was a newly minted state in the union. President Benjamin Harrison had a vested interest in Wyoming’s success and development, part of which was to encourage migration and purchase of land for settlement. Among the early pioneers was Moreton Frewen, Winston Churchill’s uncle by marriage.

The state was immense in size and sparse in population, but the soil un-farmable and unproductive. Cattle raising became the best way to for the state to monetize its massive acreage.

|

| Occidental Hotel in early Buffalo, WY |

|

Owen Wister and his book - Library of Congress |

But the slow succession of rise and fall in the plain changed and shortened. The earth’s surface became lumpy, rising into mounds and knotted systems of steep small hills cut apart by staring gashes of sand, where water poured in the spring from the melting snow. After a time they ascended through the foot-hills till the plain below was for a while concealed, but came again into view in its entirety, distant and a thing of the past, while some magpies sailed down to meet them from the new country they were entering. They passed up through a small transparent forest of dead trees standing stark and white, and a little higher came on a line of narrow moisture that crossed the way and formed a stale pool among some willow thickets. They turned aside to water their horses, and found near the pool a circular spot of ashes and some poles lying, and beside these a cage-like edifice of willow wands built in the ground.

What made Wyoming so attractive financially was its nutritious grasses of the wide-open, government-owned rangelands on which cattle freely roamed, consumed and grew fat. Called “free range,” these lands were considered in the public domain There was little to no risk for someone to purchase a herd and set it free into nature, only paying cheap wages to cowhands to round them up and take them to market for sale.

|

Mike's boss Billy Irvine (left) - Jim Gatchell Museum - played by John Hurt, Heaven's Gate - United Artists |

This business model initially generated unheard-of-profits. Envisioning even greater returns, they brought hundreds of thousands of cattle into the region which may have seemed a smart move at the time but inevitably led to a glut. And following brutally cold, severe winters in 1886 and 1887, a decline in prices, depleted herds and consumed grasslands, heavy financial losses of between 50 percent and 90 percent resulted.

Historian Helena Huntington Smith – one of the more poetic and descriptive of the writers to tackle the topic – has said in The War on Powder River that the overstocking became “the great beef bonanza… the beef bubble, or what you will.”

As their return on investment declined from overstocking and bad weather, the owners claimed that their most pressing problems was theft at the hands of the “little guy,” the ranchers, settlers and grangers who seemed to always be interfering with thievery. During boom times, an occasional loss of a calf was not seen as a problem for the owners. But when the economics changed, and profits went down, the press – largely controlled by big cattlemen – began to complain, and the public’s attitude changed.

|

Frank Canton - Johnson County Library - played by Sam Waterston, Heaven's Gate - United Artists |

In some instances, cattle owners retaliated by driving herds through the homesteaders’ cattle and taking their stock out of the country, leaving behind ruined crops and grasslands. At other times they fenced off waterways, preventing herds from watering or crossing. This is portrayed in the film Shane, where Alan Ladd Sr.’s mysterious one-named character boards with a small rancher family and helps them push back.

Cattle owners also tried to turn to the courts for redress when feeling they had been wronged. But time and again, the suspects were exonerated, often by juries of their peers who did not want to risk their enmity and revenge. Robert B. David writes that “with the jury packing, perjury, alibis and general rottenness encountered in cattle stealing cases it was impossible to convict a thief.” In Guardian of the Grasslands, author John Burroughs says that “no matter how flagrant or air-tight the evidence, Wyoming courts simply would not convict the defendant in a cattle stealing case…”

|

Alan Ladd Sr. as "Shane" Paramount Pictures |

~ The Burning Questions of Mavericks and Roundups ~

One of the poaching techniques that Mike had to watch for was “blotching” – a thief over-branding someone else’s mark on a cow so that it became different, muddled, illegible. Another was the practice of killing someone else’s cow in cold blood, called “dry gulching,” and taking possession of their young, unbranded calves, called “mavericks.”

Legally, a motherless maverick was available for the first man to claim. In Texas, where many of the Montana cowboys were from, the practice was widely accepted. But in time the law in Wyoming was changed to the cattle owners’ advantage through the Maverick Law and Roundup Law which “just created hard feelings,” Hanson says.

The issue, adds Smith, “came into head-on collision over the maverick question, the most confused, embittered, explosive question ever to bedevil the cattle range… [It] lit the powder train which led to the Johnson County explosion.”

The WSGA in 1884 helped influence passage of a new “Maverick Law.” It gave the WSGA regulatory authority to determine which cattle were mavericks and who legally owned them. The law gave the WSGA the exclusive right to schedule spring and fall roundups and directed that all rounded up mavericks would be sold at auction, with revenues to be pocketed by the association to pay for its costs.

|

Baber's The Longest Rope

|

It all felt unfair to the small ranchers and homesteaders. Under the 1884 law, a man could be branded a criminal by simply and legally buying a maverick or two with clear title using his perfectly legitimate money.

Writes Mercer in Banditti, “The rustler element howled and feeling in Johnson county rose to the exploding-point.” While the law was eliminated six years later, in 1890, it had caused irreparable damage and helped the rustler community to become more unified and focused.

The scattered herds and mavericks on the rangelands were rounded up twice a year by cowboys working for the owners, doing good work for good pay. The cattle were transported by rail to large cities for sale. The numbers were immense – in 1884 alone, one roundup gathered some 400,000 head.

The cattle owners employed another weapon known as “blacklisting.” Any man could be blocked from taking part in roundups or working for the ranches if he owned his own cattle outside of the large ownership system, in the fear that he could be tempted to poach from time to time. Lists of blacklisted names were widely distributed so that there could be no question as to who could and could not work the roundups. Writes Smith, “The no-owning rule hit everybody, the righteous and the unrighteous and the borderline cases who were merely a little human.”

One victim of the maverick law was Oscar “Jack” Flagg, a colorful character who appears throughout the accounts of the war. Having once sided with the large owners, but then blackballed after a work stoppage, he went into business for himself. Flagg bought some cattle and the brand known as “Hat” and formed a small ranch on the Powder River’s Red Fork. Using the Hat as his “semi-respectable” base of operations, Flagg became a de facto leader of the rustler community and amassed his own headcount of livestock.

The town of Buffalo, Wyoming was a center of this activity. Says Laurel Foster, director of the Hoofprints of the Past Museum, “previously the press spoke of what a great, little prosperous town Buffalo was. It was only when the conflicts emerged that the press began decrying Buffalo as this rustler haven.” As the situation grew worse, Buffalo gained a reputation as the home of “range pirates” and in the opinion of some was the most lawless town in the nation.

|

| Some of the many popular books about the War - University of Oklahoma Press - Eakin Press - University of Nebraska Press |

|

Olive (Sisler) Shonsey - Jim Barnett |

Mike was a native of Montreal, Canada, born in 1866 of Irish immigrants Thomas and Margaret (McCarthy) Shonsey. He migrated with his parents to Marion County, Ohio at the age of five and was young when his father lost his life in a lumbering- accident.

He was befriended by Thomas Hord, who became a lifelong friend and mentor. Hord and Mike traveled to Wyoming together in the early 1880s, where Mike found a job working for William E. Guthrie of the Guthrie and Oskamp Cattle Company. Guthrie also was a member of the executive committee of the WSGA, meaning Mike immediately was introduced to the owner point-of-view and saw things through their perspective.

Olive was born in 1866 in Preston County, WV, the daughter of Harrison L. "Harry" Sisler and stepdaughter of Susan V. (Martin) Sisler of the family of James K. and Margaret (Minerd) Martin. She accompanied her parents on a move to Minnesota in childhood. She was just about age 11 when her mother died, and 15 when Susan Martin became her stepmother.

|

Friends Thomas Hord (NSHS) and W.E. Guthrie (Malcolm Campbell, Sheriff) |

The only known offspring of their union was a daughter, Anna S. Traver.

The first marriage ended, for reasons not yet known, and the widowed Olive and daughter Anna moved to Nebraska. There, on Jan. 14, 1891, at the Potter House in O'Neill, she wed a second time to 26-year-old Mike Shonsey.

Olive is named unflatteringly in Frederick Manfred’s book of fiction, Riders of Judgment. In that reference, the protagonist, rustler Cain Hammett, based on Nate Champion, snaps at Mike’s character, saying “You have a woman of your own to dribble on.”

Mike became widely known for his exceptional skills as a cowboy. Records show that in 1886, working for Guthrie-Oskamp, he managed the branding of 2,551 calves. Writes Gage, he “was a very tough Irishman who knew cows and cowboys. He was wholeheartedly on the side of the barons, but would have made a top-hand rustler, if he had bent his talents that way.”

|

| Olive's stepmother, father and brother Warren (with horse) Courtesy Cheri Denise Blaylock-Lovell |

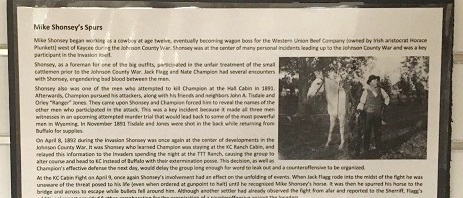

Mike's spurs - Hoofprints of the Past Museum |

Mitch was a blond, had a pocked face of slanted ovals suggesting the Mongoloid, and was somewhat round-shouldered. He wore brown leather boots, stiff leather chaps, cowhide vest, cowhide cuffs on his wrists, and tan gloves… He was known as a sneering bully to his hands and a braggart to his bosses. He would never admit wrong. When someone brought up a point, Mitch either knew all about it already or didn’t consider it worth knowing. Over a drink a man might tell a windy [prolonged, empty talk] that nobody would much question, but if Mitch were present he’d be quick to come up with a windy that was bigger, better, and windier.

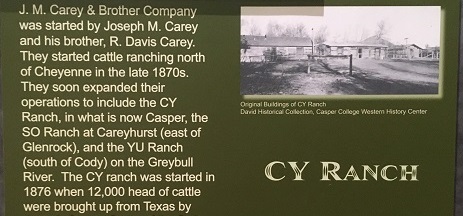

By 1891, Mike had become manager of several ranches, among them the “EK” owned by Englishman Horace Plunkett, all of which were going broke, says Hanson. Then in 1892, he worked as roundup foreman for the Western Union Beef Company and the CY Ranch along the North Platte River, with their cattle straying over hundreds of miles. The CY was owned by Senator Joseph Carey and the beef company managed by former Wyoming Territory Governor George W. Baxter and foreman Edward T. David.

A foreman typically earned three times the wages of a common cowboy, and a chief detective could earn $2,500 a year, a very large sum at the time. A detective’s job was to inspect brands, pick up strays and protect herds from natural and manmade threats.

|

Mike's rifle - Nebraska State Historical Society - and a display about one of his workplaces, the CY Ranch near Casper - Fort Caspar Museum |

|

|

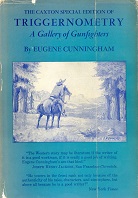

Triggernometry book

|

Eugene Cunningham, writing in Triggernometry, said that an old-time joke among the cowboy set was that a stock detective like Mike “was just another name for thief killer.” It was important for detectives to work in secrecy and at times use espionage to infiltrate hostile groups to learn their intentions. Another skill was the ability to “call the brand” – how to identify brand marks to determine proper ownership.

|

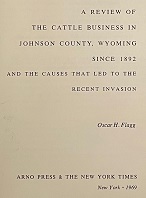

Jack Flagg's book

|

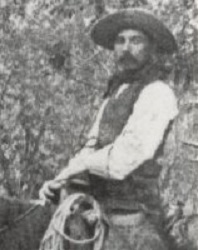

Mike’s first entry in the Johnson County War story occurred in 1888. That year, he got into a dispute with the colorful Jack Flagg, who became an enemy. Flagg later wrote his own memoirs of the events, published posthumously as A Review of the Cattle Business in Johnson County, Wyoming Since 1892. At one particular roundup, Flagg accused Mike of “blotching” over the brands on the hides of his cattle. Flagg demanded to know if Mike had blotched any of the Flagg cattle, and Mike said no. But others in the party claimed Mike in fact had done otherwise. Flagg then began striking Mike with a short leather whip known as a “quirt.” Flagg later claimed that Mike “attempted to draw his six shooter but dropped it, then he rushed in and grappled me, striking me a pretty hard blow on the nose. I then made an effort to throw him from me when his pants tore loose.”

Writes Davis about Flagg, “All indications are that he won the fight but secured Shonsey’s enduring hatred.” Smith says that “Flagg of course being a writer had the last word, and he claimed the moral victory.”

Author D.F. Baber, writing in The Longest Rope, described another encounter between Mike and some trappers along a trail near the Shonsey residence -- “Mike hailed us and asked what luck we had been having.” He offered for the men to trap beaver and muskrat “out my place” which had been “spoilin’ my hay ground an’ raisin’ hell generally.” As the party moved toward Mike’s, it was “a hard drive down… The road was narrow and full of chuckholes and wouldn’t make a decent cow trail, so we didn’t try to make good time with our wagons.”

|

| Panel display about Mike in the Hoofprints of the Past Museum, Kaycee |

~ Mike Tangles with Nate Champion ~

Nate Champion Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum |

Champion had begun working in the early 1880s and moved up to wagon boss. He is known to have attended an 1884 meeting of cattlemen in Cheyenne to try to resolve the maverick issue. But after being fired at a ranch and then blackballed, he operated his own herd of rustled cattle. Writes Baber in The Longest Rope, Champion “was a born cowhand, a longheaded businessman, and a wizard with a long rope and six-gun. His reputation as a square shooter had made him a leader among the nesters and lone-player stockmen. That was what started the big men to losing sleep.”

In the winters, while his herd was freely roaming on the range, Champion would “hole up” in a small cabin and wait out the months of hard weather. One of his spots for winter hibernation was the Hall cabin in a secluded valley. Hanson calls Champion “a natural leader in a fight but not otherwise” and says he had wanted the ill-fated John A. Tisdale to lead the small ranchers instead.

James Mitchell Clarke, in the foreword to Banditti, says that Champion was “as brave as any man on the northern plains.” Sheriff Malcolm Campbell, on the side of the cattle owners, claimed that Champion was “Fearless in the face of any odds and with the reputation for being the quickest man with a sixgun in this country, he was a typical leader for as hard a lot of rustlers as could be found anywhere in the West.”

Author O’Neal calls him “quiet and brave” who was known for his skills as well as “a very active rustler and one of their leaders.”

|

| Nate Champion (center) and brother Dudley (right) on a roundup Courtesy Johnson County Library |

|

Nate Champion as portrayed by Christopher Walken in Heaven's Gate (United Artists) and Tom Berenger in Johnson County War - ©MCMLXXXVIII Touchstone Pictures |

But in another account, it was Mike who scattered his nemesis’ herd, with Champion and friends later riding in with guns to gather them back together. Writes Davis, “In the West, known for its hospitality, such a gratuitously rude action would have been considered particularly offensive … [and] created lasting hard feelings between the two men.”

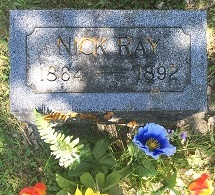

At yet another time, Flagg, Champion and Nick Ray – who also would end up dead -- met up with Mike on a road. In their version, Mike wanted to ride into their herd and pull out strays he claimed were his. Champion allegedly told Mike, “You ain’t riding into that bunch to cut nothing out.” A staredown resulted for an extended time, with the Champion group suspecting that Mike and his group would scatter the entire herd after nightfall.

Author Smith addresses the complex personalities at work in the ever-dysfunctional relationship between Mike and Champion.

The two-faced behavior of Shonsey puzzled the blackballed men for many a year. Enmity would break out of him one moment, followed by gestures of seeming friendliness. He even made one to Flagg, who was surprised to find his name suddenly taken off the blacklist that spring, while Shonsey invited him to go on the roundup and gather his cattle. Not in Jack Flagg’s time, nor for years after, did the reason for the Irishman’s mysterious behavior come to light, and then it was in an interview with a Wyoming historian in old age. In addition to his regular work he was drawing pay from the cattlemen to report on the movements of the rustlers. Shonsey was a spy.

|

| Nate Champion statue in Buffalo, Wyoming |

~ The Cattle Kate Assassination Incites Fear ~

Cold-blooded killing became a tactic that the Wyoming cattle owners used to take back control of the growing problem. In 1889, citizens Ella Watson and her husband James Averell ran a store post office and small cattle ranch near Independence Rock about 50 miles southwest of Casper. Despite their innocence, they became the first casualties.

Their first mistake had been amassing several hundred acres of land on adjoining tracts and restricting water access to neighbors. Then James published a letter to the editor of the Casper Weekly Mail exposing illegal Sweetwater Valley land grabs by cattlemen. And so on the afternoon of July 20, 1889, the pair forcibly were taken at gunpoint from their home by six representatives of the cattle owners, driven in a buckbooard to nearby Spring Canyon, and hanged from a cottonwood tree.

|

| L-R: the doomed Ella Watson, a.k.a. "Cattle Kate" -- portrayed in Heaven's Gate by Isabelle Huppert and in TV's Johnson County War by Rachel Ward - courtesy United Artists (center) and Hallmark Channel (right) |

The murders sent waves of horror all throughout the state and beyond. Smith writes that the premeditated act was “probably the most revolting crime in the entire annals of the West.”

A coroner’s inquest was held and identified each of the six killers. Word of the scandal spread rapidly that two people had been lynched and that one sensationally had been a woman. Two unscrupulous reporters with the Cheyenne Daily Leader – a pro-cattleman publication – seized the opportunity to spin the story, creating fiction to blame the victims and not the perpetrators. Their initial article accused the dead couple of stealing cattle and ignoring orders to leave the area, and Ellen was labeled as a “virago” – foul-tempered, domineering and violent.

|

Kris Kristofferson as Ella's husband in Heaven's Gate - United Artists |

In his thoroughly researched deep dive into this crime, The Wyoming Lynching of Cattle Kate 1889, George W. Hufsmith writes that “the catchy name stuck, and [the Leader] gleefully pounced on the misidentification with all fours the very next day and continued to use the name Cattle Kate in [the] newspaper. But the damage had already been done and has continued for a whole century until Ellen Watson has become more frequently known as Cattle Kate than by her real name.”

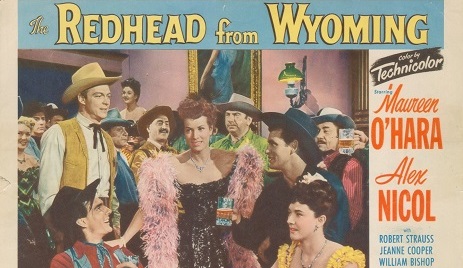

Ella’s grisly death took on its own legacy and notoriety in books and film as “Cattle Kate,” all in the persona of a prostitute. In many accounts she was accused of accepting stolen cattle as payment for her services of flesh. She was played by Maureen O’Hara in film The Redhead from Wyoming, a highly fictional and inaccurate view of elegance, style and wealth in her trade.

She also was portrayed by Isabel Huppert in Heaven’s Gate, operating a whorehouse and part of a love triangle between Kris Kristofferson and Christopher Walken, and by Rachel Ward in the Johnson County War, based on the fictional Riders of Judgment, where she was known as “Nella Wells” and nicknamed “Cattle Queen” or “Queenie.”

|

| Film about Cattle Kate starring Maureen O'Hara - Universal Pictures |

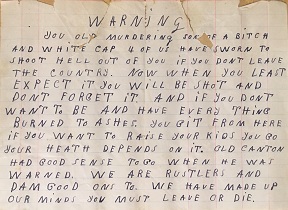

"Beware" note by rustlers - Johnson County Library |

Baber writes that their deaths “stirred up the whole country, and the newspapers all over the world were full of it.” It became clear that the motive was to threaten small ranchers that their lives were at risk. And they pushed back.

One morning, the proprietor of the Munkres and Mather hardware store in Buffalo came to work to find a hostile hand-lettered note pinned to his front door, clearly inscribed by a member of the rustler community:

WARNING - You old murdering son of a bitch and white cap 4 of us have sworn to shoot hell out of you if you don't leave the country. Now when you least expect it you will be sot and don't forget it. And if you don't want to be and have every thing burned to ashes. You git from here if you want to raise your kids. You go. Your health depends on it. Old Canton had good sense to go when he ws warned. We are rustlers and dam good ons to. We have made up our minds. You must leave or die.

|

Manfred's work of fiction Penguin Publishing |

Wister was a serious and respected writer who greatly influenced the public’s perception of the charm and allure of the dangerous world of the cowboy west, writes Digby Baltzell. In his book Puritan Boston & Quaker Philadelphia, Baltzell says that The Virginian became a bestseller, “an attempt to portray a dying cultural type in the manner of Melville’s whaling captains or Cooper’s backwoodsmen” and “was the prototype of the cowboy novel and film.” Thus the Cattle Kate killing and Johnson County War can be said to have shaped the Western film genre that became so popular in American culture.

Two years passed quietly before the specter of murder again reared its ugliness. Then on June 4, 1891, Newcastle settler Thomas Waggoner forcibly was removed from his home, while his wife watched in dread, and taken to Dead Man’s Gulch, where he was hanged. More than 1,000 horses were found in his fields, leading to speculation that they were rustled and that he had been killed as revenge. Wisps of rumors spread that one of the hangmen was a WSGA stock detective.

~ Shots Fired in the Hall Cabin Near the Bar C Ranch ~

The prospects for heightened conflict in Johnson County began to take a more defined and ominous shape in the fall of 1891, when Mike learned that his nemesis Nate Champion and Ross Gilbertson were bunking nearby in a rented small log house, known as the “Hall Cabin” near the Bar C headquarters. Mike made the first move, riding to their place in the secluded mouth of the canyon.

He arrived “on the pretext of a parley about a horse trade,” writes Smith “It was a curious gesture in view of their recent quarrel, and Champion received him coolly, concluded later that the purpose of the visit was to spy out whether Champion was at home.”

In the story told in The Longest Rope, once Mike departed from the meeting, Champion told his mates that “This is twic’t we’ve had company this week… Mike Shaunsey was through hyar on his way to Douglas to the political convention, an’ spent the night with us. We’ll hafta start puttin’ on the dog if them cattlemen ‘re goin’ to come payin’ us social calls…”

|

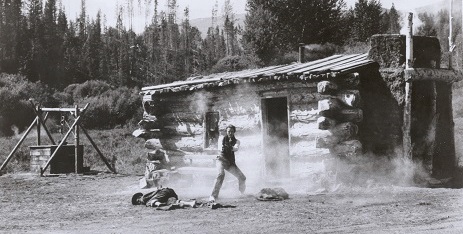

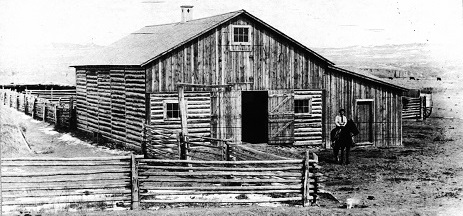

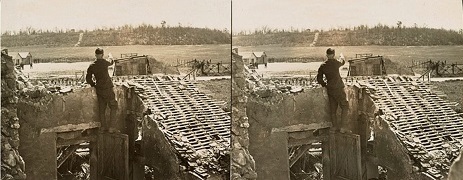

| Hall Cabin near the Bar C where Mike allegedly and unsuccessfully helped assault Nate Champion and Ross Gilbertson - Courtesy Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum |

|

Jack Gage's book Flintlock Publishing |

Jack R. Gage in The Johnson County War Is/Ain’t a Pack of Lies says that Champion “never claimed to have seen Mike Shonsey [that day] but he, Champion, blamed Shonsey as much or more than anyone else...”

Champion and a companion began a pursuit of their attackers, seeing other discarded weapons and clothing along the way. They followed tracks to an empty campsite in Beaver Creek Canyon, where they saw a bloody tarpaulin, evidence that one of their shots had found its mark.

The camp was not far from the Mike’s homeplace, and the two parties encountered each other. Writes Smith, “Champion whipped out his gun and demanded to know the names of the attackers. ‘I know who they were but I want to hear you say it. Don’t lie to me or I’ll kill you’.” Mike had no other choice than to comply, and in doing so disclosed Canton’s name among the others. With this gesture, his life was spared, but the implication of his colleagues put them at risk of arrest and charges of attempted homicide.

Writes Hanson, “Champion, J.A. Tisdale and Orley ‘Ranger’ Jones were all there and heard Mike spill his guts. That made all three of them witnesses the way the law read then. In five months all three had been murdered.”

~ A Plan for War ~

In 1891, Jones and J.A. Tisdale -- suspected as rustlers – were shot to death, “dry-gulched” like mother cows, gunned down in cold blood. Jones, a former cowboy-turned-homesteader, was killed from behind while driving his wagon home along an isolated trail, filled with lumber for a new house. Tisdale was hit in the back, in his wagon too, on the road at Haywood’s Gulch (today Tisdale Gulch), en route to home with Christmas gifts for his children.

|

Robert B. David's book Wyomingana, Inc. |

Without any other protections, the cattle owners under the guise of the WSGA began to plan a more severe answer to their rustler crisis, one that was intended to create the deepest terror, a type of “final solution.” The plan was adopted in a secret WSGA meeting in Denver in April 1892. There are whispers that among the planners colluding to protect their self-interests – or recruited as allies – were Acting Gov. Amos W. Barber and Senator Carey, who owned the CY Ranch where Mike worked. Major Frank Wolcott, who managed a ranch, and H.B. Ijams, both former secretaries of the WSGA, were among the leaders of a hit squad dubbed the “Invaders.” Even President Harrison was said tacitly to have approved the plan, although this was never proven.

Smith writes that the “planning of such a scope could only have taken place on a very high level is obvious on its face; that many if not most of the leading men of the state were mixed up in it...”

The WSGA’s plan was to recruit expert mercenaries to shoot or hang any and all influential thieves through a rapid, secretive blitzkrieg type of invasion, hinging on secrecy. “The raid must be quick and silent,” David writes, “and should withdraw from enemy territory without a witness against it to testify in court.”

A list of individual assassination targets was drawn up, dubbed the “daisy list” from where the names of known rustlers previously had been identified.

The cattlemen’s next steps were to pool funds, recruit shootists and to arm them with guns, horses, blankets and supplies. Some 25 riflemen from Texas were hired at a fee of $5 per day, plus expenses, and a bounty of $50 each to be paid for every man eliminated. One of them, D.E. Booker, also known as “Brooke,” bore the catchy nickname “Texas Kid.” Word of the recruitment got around and was no longer a secret.

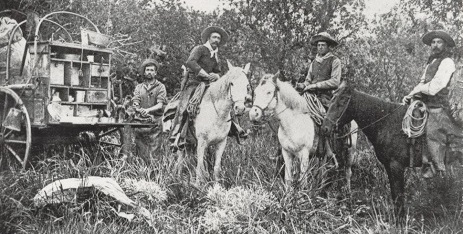

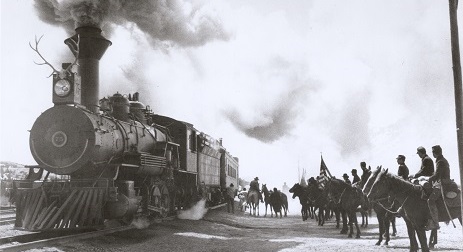

The professional gunmen who agreed to the venture gathered in Cheyenne and boarded a train, cruelly nicknamed the “Daisy Special,” and rode north to Casper. When the train pulled out of Cheyenne, said author Smith, it was “undoubtedly one of the worst-kept secrets in the history of the West.” Upon arrival at Casper, rumors began swirling as to the intent of this mass of armed men moving as one body into the countryside, destination unknown.

|

| “Daisy Special” train arrives in Wyoming, carrying mercenary Texas gunmen to begin the raid, as portrayed in Heaven’s Gate - United Artists |

One of the party was Dr. Charles Bingham Penrose, brother of Pennsylvania Senator Boies Penrose. He initially carried the daisy list of targets. It might seem unusual that a physician be taken on such a hit-and-run mission as a potential eyewitness. But it suggests that the cattle owners anticipated bloodshed. The doctor himself later wrote, Gov. Barber “knew all about the expedition and he advised me to go on it.”

The plan was for the hit squad to first to go Buffalo, Johnson County, to kill Sheriff William “Red” Angus and his deputies. From there they would take occupancy of the town, kill more on the list and then ride out into the country to destroy ranches and drive out settlers. Telegraph wires were to be cut to prevent a spread of communication, a task apparently handled by one of Mike’s bosses, Edward T. David.

In their indiscreet planning, the cattle owners of the WSGA counted on the benefit of a public response based on “western opinion” – an indifference to principle and belief that a man should fight for his rights. Canton wrote that two-thirds of the town of Buffalo were “intimate friends” of the cattle owners and believed “we could explain the true situation to them; that they would not only assist us with their influence, but would join our party if we needed them.”

But this assumption was deadly wrong. In estimating public opinion, the cattlemen ultimately failed. They “expected the people to rise in their support,” Smith writes. In fact the “people rose, but in such a wave of fury as the West has never seen before or since…”

~ The Cattlemen Attack Nate Champion and Nick Ray ~

|

| Site near the Nolan cabin at Kaycee, WY where the invaders gunned down Nate Champion and Nick Ray |

Mike’s role in the War generally was as a scout and intelligence-gatherer and later as a gunman. At this point in the fictional tale in Riders of Judgment, Mike receives an entire six-page chapter devoted to his and Olive’s story. In leaving home on April 7, 1892, to carry out his part in the attack, it says, he “bade his goose of a wife good-bye, and his little boy, and saddled up and rode over the hill,” wearing a yellow rain slicker.

That night, Mike made the first move when he rode to the Nolan Cabin at the KC Ranch where he knew Champion and others on the daisy list were staying. The group included a dozen rustlers who were Democratic delegates en route to the state convention in Douglas. Today a garden shed stands near the site just south of town, next to a house and meadow across Old Barnum Road from the Powder River Campground.

Mike allegedly made up a ruse, possibly about a horse trade, and as the sky grew dark, asked to bed down for the night. Mike recognized one of Champion’s cabin-mates as the energetic rustler Nick Ray.

For reasons not known, Champion and his bunkmates that evening were “careless with their conversation in his presence,” David writes, “talking boldly before him of their plans, telling of their scheme of taking a bunch of stolen cattle over to the graders’ camp.”

The next morning, April 8, Mike left the Champion cabin and rode 16 miles to meet his party of invaders. He told them what he had heard, claimed there were 14 daisy-listers together with Champion under one roof, and recommended that an assault begin immediately. Canton and Major Frank E. Wolcott, who assumed the role as commanders of the company, made the decision to commence.

In Riders of Judgment, Frank Canton’s fictional character (Hunt Lawton) “raged inside” about the decision to ambush Champion and directed his anger to Mike’s character (Mitch Slaughter). “For two cents he could have plugged Mitch,” Manfred writes. “He hated Mitch’s sly slanted face, hated the way Mitch sat in the corner, smirking to himself because his idea had been accepted after all.”

Another of Mike’s bosses, William E. Guthrie, also was part of the group, as were reporters for the Cheyenne Sun (Ed Towse) and Chicago Herald (Sam T. Clover). Their plan included managing the public relations spin of the expedition to minimize any negative fallout.

In the fateful evening, Mike and three Texas gunmen “swung into their saddles and headed into the cold night,” writes O’Neal. Their objective was to ride back to the KC Ranch, scout Champion and company in greater detail and then make one final report back to the invaders.

As Mike’s party arrived at the KC, they could hear fiddle-playing and laughter coming from inside. They rode to a gulch about four miles away, where the rest of the cattlemen had advanced, and reported that the coast was clear for an assault.

Their plan was to arrive at the cabin before sunrise on April 9, 1892 and to plant a load of explosive powder. They would blow up the cabin in the darkness and shoot any man who came out. But as fate would have it, they arrived too late, after the morning’s first light. They noticed an unfamiliar wagon on-site, suggesting there might be others with Champion who were not on the daisy list. The invaders decided to wait and watch.

Mike was ordered to take a position in a gulch south of the cabin, along with Jack Jones, Elick Kinzie and three of the Booker clan.

|

| With friend dying, Nate Champion (Christopher Walken) fights for his life during the raid, as seen in Heaven’s Gate - courtesy United Artists |

The first man to leave the cabin was not an assassination target but rather a visiting trapper, Bill Jones. He could be seen holding a water bucket that he wanted to fill at the nearby Powder River. Once he was out of the line of sight of the cabin, he was apprehended. A half-hour later, a second man left the cabin, William Walker, also not on the list. He too was taken quietly and held at gunpoint. Many years later, Walker told his story which became the 1959 book The Longest Rope.

Wondering what had become of the first two men, Nick Ray then emerged from the cabin. He was on the list, and took perhaps 10 steps. The Texas Kid fired the first shot and hit his man. Ray collapsed and then was struck by a second round of bullets, badly wounded. Champion could see out the door and began returning gunfire, as his friend struggled to crawl back inside. There were no others inside, as the rest had departed the day before for the state political convention, and the invaders could not understand how Mike’s headcount estimate had been so off.

Shooting continued intermittently over the span of several hours. None hit anything human in either direction, and the cattlemen’s bullets could not penetrate the cabin’s thick log walls. In what seems a remarkable peace of mind and self-awareness, Champion scribbled entries in his diary throughout the ordeal. But there was nothing to be done to save the life of his wounded friend. Death finally overtook the badly shot up Ray.

Now the sole survivor, Champion remained armed but for all intents was stuck in a deathtrap as there was no way to exit and get away. With the element of the invaders’ secrecy gone, word spread quickly throughout the network of ranches in the county. Terrence Smith lived within earshot, heard the firing and then rode off the warn others, in Paul Revere-like fashion. He arrived in Buffalo and told people what he knew. Rancher after rancher bent on defending themselves “seized their guns and rode to Buffalo, ready to do battle,” O’Neal writes.

|

| Bridge which Jack Flagg and his stepson crossed near the Nolan Cabin during the shootout - courtesy Johnson County Library |

The situation at the siege grew more complicated. At about 2:30 p.m., out of the blue, Mike’s enemy Flagg and his teenage stepson Alonzo Taylor rode past in a buckboard wagon, expecting to stay the night en route to the state convention in Douglas. Flagg was instantly recognized – the same man who had beaten Mike in a fight four years before and widely known as a rustler. Shots were fired, and Flagg shouted for the men to “go to hell” thinking they were just joking. As man and boy tried to speed away, they were followed for about a mile-and-a-half, with a distance of about 1,000 yards in between. The pair got away without harm, after cutting loose their wagon, and speedily rode to Beaver Creek to sound their own alarm and set up an ambush in the dark with about 20 other men. But their position was revealed when one of the party, Al Smith, dropped his six-shooter and it went off.

The invaders knew they would have to speed up their attack. Flagg’s abandoned wagon was seized and hay and wooden posts were placed in the box and lit afire. It was pushed to the cabin with the intention of igniting the timbers and burning Champion out.

This scene has been played out in a number of films with many embellishments and inaccuracies. In the Hallmark version, Champion (Berenger) mows down some 27 shooters with his extraordinary firing accuracy. In Heaven’s Gate, it’s not Flagg riding by in the wagon, but Cattle Kate instead.

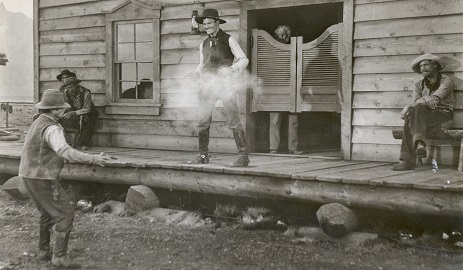

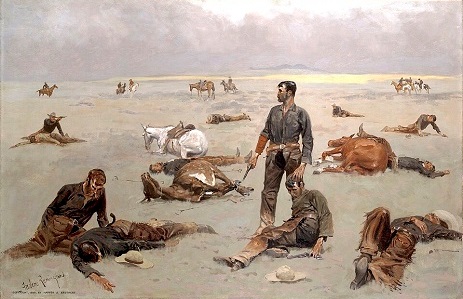

As the cabin ignited, Major Wolcott decided to deploy his best gunmen on the other side of the building, in a draw to the west, and conceal themselves in the sagebrush. He was quoted in The Longest Rope, saying “That is where Nate will be sure to run, if he don’t run into a bullet before he gets that far. I will give that job to Mike Shaunsey [sic] and the Texas Kid. They are probably the best shots we have.”

Seven hours into the siege, with early nightfall approaching and the cabin engulfed in flames, Champion knew that his only option was a mad dash for safety. He moved to a dugout in the back of the cabin and made his exit through its low-slung roof, and then began to sprint in the cold dusk air. He made it across a meadow and as far as a gulch before being shot and killed point blank. Baber' writes that the Texas Kid splintered his left arm with his first shot – and then “met a hail of lead” from Mike’s rifle. But Baber was writing fiction, and Mike’s role in the killing is not known.

|

| Above: Howard Glaskey's painting of Nate’s death in a hail of bullets, published in On Special Assignment by newsman Samuel T. Clover. Google Books. Below: Gulch where Champion died, with a cross and flowers (circled) marking the spot. Johnson County Library |

|

The invaders gathered around Nate’s corpse as the cabin continued to burn. The diary was removed from his pocket. A note was pinned to his shirt, reading “Cattle Thieves, Beware!” Canton reputedly reached for the dead man’s rifle and said “I got my gun back.” Then at sundown, having completed the first part of their plan, they departed and spent the next hours riding through the night in the direction of Fort McKinney. There, they thought, they could find shelter and protection. Moonlight reflecting off the snow helped them see their way through the dark.

In assessing the day’s events, writes Gage,

…some of the invaders may have felt that at least part of their mission had been accomplished. On the other hand, some others must have thought it was a rotten dirty shame, and that what they had set out to gain was now lost… The thing the invaders were guilty of, along with their crimes, was doing everything they did without reckoning at all with every other man, woman and child in the whole county.

Canton, in his autobiography Frontier Trails, admiringly says that Champion “came out fighting and died game. If he had been fighting in a good cause, he would have been a hero.”

The Champion/Ray funerals were widely attended. In the version told in Riders of Judgment, the officiating pastor eulogized that Champion would “always be remembered as the man who alone overthrew the feudal system of the old frontier and turned the cattle kingdom into a free country.” The remains were lowered under the sod of Willow Grove Cemetery

|

| Graves of Nate Champion and Nick Ray, Willow Grove Cemetery |

~ Coroner’s Inquest Indicts Mike and 44 Others ~

|

Sheriff Red Angus

|

A county coroner’s inquest was called by W.B. Robinson to investigate the deaths. The 17-year-old Alonzo B. Taylor, testified that he and his stepfather Flagg had been fired upon as they drove past the KC Ranch and that Mike had fired directly at them. When the teen identified the shooters, Mike’s name was second on his list.

Flagg said in his testimony that as he approached the KC, he spotted the ring-tailed horse Mike had been riding all winter. He said that “the man whom I recognized as Mike Shonsey jumped off and begun firing at me. They fired so many shots, I cannot tell how many, but at least 30 shots were fired at me in the next 300 yards.” Witness Percy Brockway, age 18, also named Shonsey.

Witness Terrence Smith said that when returning to the cabin after the fight ended, he saw dead and wounded horses and cattle as well as the earthen breastworks the invaders had dug. Local physician Park Holland studied the two corpses and in Champion were found 28 bullet wounds. He added that all of Nick Ray’s internal organs had burnt out, the limbs gone, the face burned out and a small portion of backbone protruding out.

The jury on April 16 returned a finding that the two dead men had been “wilfully and feloniously killed and murdered” by a list of 45 men, with Mike’s name among them. But the 45 men were still on the loose.

~ The Invaders Retreat to the TA Ranch ~

Back in Buffalo, the townspeople “went wild” with fury, remembered on onlooker. As with any story told in high excitement, it took on an exaggerated tone, with rumors that the cattlemen wanted to drive out the settlers and burn out all of their homes, “and all kinds of ridiculous stories,” writes Canton.

Enraged ranchers came into Buffalo in hordes, armed and ready to defend their rights and repel the enemy. One storekeeper offered the townspeople the freedom to take any of his merchandise – guns, ammunition, food and blankets – to prepare for the coming counter-assault. The amassing posse of farmers, homesteaders and small ranchers has been called by one historian as a “tidal wave.” A headcount of 300 prepared to move out to exact revenge on the cattlemen, whom they dubbed as “whitecaps,” a derogatory reference to the white sheets worn by the Ku Klux Klan.

At this stage of the story, the cattlemen were in a retreat and heading straight north toward Buffalo. En route to Fort McKinney, about 30 miles away, they stopped to rest at Mike’s workplace, the Western Union Beef Company headquarters. There, he had arranged for about 100 well-fed, rested horses to be waiting as replacements. Mercer and David both claim that these horses had been “especially fed for weeks, in anticipation of the emergency.”

|

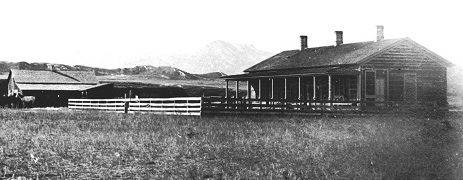

| TA Ranch barn then (Jim Gatchell Museum) and today, site of the 3-day siege between furious homesteaders and the cattlemen and their Texas gunmen. Bullet holes may still be seen in the building today. |

|

One of the leaders of the party, Major Jim Dudley, alias Gus Greene of Texas, was overweight and struggled with his new horse. Mike tried to help him by bringing him four or five replacements while the major grew impatient and exasperated. In a horrific twist of fate, Dudley tried to mount his original, exhausted horse, his gun accidentally went off, and a bullet hit him in the knee. He died not long after from the infected wound, a self-inflicted casualty.

Now on their fresh mounts, the cattle owner group resumed their “sinister march” in the dark, writes Smith, “arrogant, mulish, confident in their overwhelming strength and no sense of urgency.”

|

Major Frank Wolcott Courtesy Malcolm Campbell, Sheriff |

From the TA they continued in the direction of town but were intercepted by a messenger who told them Buffalo was in an uproar and a posse was en route. The invaders returned to the protection of the TA. Sheriff Angus learned of the change and shifted the direction of pursuit.

At Wolcott’s order, the invaders began to prepare for a siege, even though they been forced to abandon both wagons bearing telegraph wire, cutting tools, guns, explosives and poison and even the confidential daisy list.

They took occupancy of the TA’s one-story ranch house and nearby barn. Because the buildings were low slung in the terrain, the men could not see in all directions, especially over a knoll to the west. A small team was dispatched to dig out breastworks from the cold earth in several locations away from the house and barn, with a trench cut and heavy timbers stacked around the sides. Holes were cut in the sides of the barn through which the cattlemen could point their guns. For food, they slaughtered a cow, filled two barrels with drinking water and found coffee, flour and potatoes in the cellar. With such sufficient supplies, they were confident they could hold off their attackers indefinitely.

Over the rest of the day and into the night, the armed posse advanced as a body in groups of 20, 30 and even 40. They arrived at the TA after the dark, getting to within several hundred yards of the ranch buildings. The next morning, April 10, they began to fire their guns, kicking off a siege that lasted for three days and grew to a count of 400 furious shooters.

Writes Smith, upon realizing the enormity of the approaching citizens, “The invaders were dumfounded. They had never looked for anything like this. They seem to have supposed that a private army could march through the countryside at will, burning and shooting, without arousing opposition.”

Sheriff Angus went so far as to issue a scorched-earth directive, with “no calling for a surrender, no parleying to give the stockmen an opportunity to give themselves up to the law – merely a volley from the posse directed at the besieged,” David writes. Angus also ordered the cattlemen’s horses to be shot. In the opinion of author David, who was biased in favor of the invaders, a 180-degree shift had taken place and the citizenry assumed the persona of a killing body.

Adds David, “The record in no wise shows any desire of Angus for anything but the death of these stockmen, a condition of mind which is impossible in a proper law official.” But others believe Angus’ motive was to take them alive, lock them up and prosecute them for murder.

|

| TA Ranch house then (Jim Gatchell Museum) and today |

|

As both sides continued to exchange gunfire for hours, the attackers dug trenches and advanced ever-closer to the house and barn. On the cattlemen’s side, Canton feared that barbed wire would be strung around the perimeter to prevent their chances of escape. In fact an attempt was made to erect barbed wire but the cattlemen’s gunfire came too close.

At this point, at the TA Ranch, Olive Shonsey re-appears in the story, as a character in The Longest Rope, spelling the family name differently, and from the point of view of the furious townspeople:

Mike Shaunsey’s wife was there, too, scared half to death. She had heard the bombarding and knew something had gone wrong, and that Mike was probably mixed up in it. Even the womenfolks, who threw all kinds of fits when their own men got into a jackpot, didn’t worry a bit over nesters getting wiped out. Mrs. Shaunsey had no idea how the cattlemen and their killers happened to be over on Powder River, instead of up at Buffalo, and we sure didn’t go out of our way to explain. The cook scowled at us and shook his head when she asked questions, so I reckon we were not supposed to tell her, anyway. Besides, we figured a little worry might do her good. And I imagine it did get her somewhat prepared for her next meeting with Mike, when she saw him looking through the bars from the wrong side.

The peppering of gunfire continued into the next day amidst intermittently stormy weather, but without any wounds. David describes the scene as a continuous roar in the valley – “Above the circle of breastworks was a ring of smoke from the rifles continuously discharged at the ranch, while from the fort and ranch building which themselves were shrouded with blue-gray smoke, came accurate shots which made the advances dangerous…”

|

| "Go-devil" made from the cattlemen's abandoned wagons Courtesy Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum |

Model of men pushing the

"go-devil" Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum |

It became ominously clear to the cattlemen that they were doomed. Some dreaded the worst but later said they preferred to die than give up. No man weakened.

Their diet at that point consisted of water and beef but otherwise only raw potatoes. No one had much sleep. Mike’s boss, Edward T. David, later admitted that “Each man gave up hope in his heart that day. Each knew the impossibility of rescue, and all understood the ruthlessness and vindictiveness of some of the most active of the besiegers.”

A younger one of the cattlemen, Dowling, offered to make a run in the dead of night to telegraph authorities for help. He and Mike “stole out of the house and down to the bank of Crazy Woman Creek,” David writes. “Here they crawled along the stream for several yards, when Shonsey stopped and shook hands with the young fellow, wishing him luck as he bade him goodbye. Dowling’s farewell words were, ‘you can trust me,’ before he stole away in the dark.”

Dowling successfully rode into Buffalo, and learning that the telegraph wires had been cut, traveled another 100 miles over more than a day’s time to Douglas, where the wires were fully intact. There, he sent a telegram to Gov. Barber in Cheyenne, asking for help.

|

President Harrison and Senator Carey Library of Congress |

Although the telegram arrived while the president was asleep, the senators and secretary of war were able to get word into his bedchamber. Harrison then issued a variety of telegrams, replying to the governor that “I have … ordered the secretary of war to concentrate a sufficient force at the scene of the disturbance and to co-operate with your authorities.” Instructions were issued that Brig. Gen. John R. Brooke and his soldiers at Fort McKinney were ordered into action but only at the governor’s direction and no one else’s, including civil law enforcement authorities.

“This regulation was arranged in advance of the invasion,” Hanson says.

Writes Baber, “That was what the cattlemen had been working for all along. That was their ace-in-the-hole, and they didn’t aim to lose any tricks.”

At the final stage of the siege, more than 400 rustlers were ensconced in newly dug trenches while other spectators watched from a distance. The exchange of gunfire continued off and on. The go-devil kept moving forward and eventually reached a position about an eighth of a mile from its target. David estimated that by noon of what turned out to be the final day, the vehicle would have reached the buildings, with deadly consequences to have followed. As the circle drew ever tighter, some of the cattlemen abandoned the barn and outbuildings and moved into the main ranch structure. And waited.

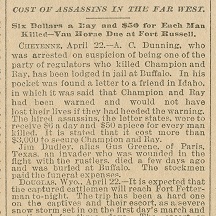

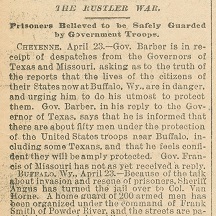

Reports in the New York Sun said that one of the invaders, A.C. Dunning, was carrying a letter in his pocket "to a friend in Idaho, inwhich it was said that Champion and Ray had been warned and would not have lost their lives if they had heeded the warning. The hired assassins, the letter said, were to receive $6 a day and $50 apiece for every man killed. It is stated that it cost more than $3,000 to secure Champion and Ray."

|

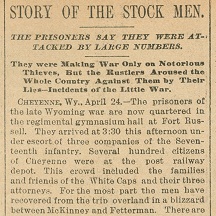

| New York Sun newspaper coverage of the raid, clockwise from upper left -- "Cost of Assassins in the Far West," April 23 - "The Rustler War," April 24 - "Story of the Stock Men," April 25 - and "The Hated Stockmen," April 29, 1892. |

|

~ Rescue, Surrender, Imprisonment and Release ~

What saved the men holed up at the TA Ranch was the arrival of the mounted garrison from Fort McKinney. One writer quipped that “for the first time in sixteen years, United States troops were called out to preserve domestic peace…”

And at 6:30 o’clock the next morning, April 13, the troops of the 6th Cavalry under the command of Col. James Van Horn arrived with bugles loudly blaring, having traveled down the road and then cutting across the fields from the west. The army halted about 800 yards from the ranch buildings, to confer with Sheriff Angus, but were visible and audible to all. The gunfire ceased – the counter-attack was over.

|

| The 6th Cavalry to the rescue of the invaders, en route from Fort McKinney, as depicted in Heaven’s Gate - United Artists |

Writing in Banditti, Mercer says that if the cavalry had been delayed even for two hours, the go-devil would have gotten close enough for the posse to begin throwing dynamite into the cabin and barn and drawing the cattlemen out to their inevitable slaughter. The rescue came together so smoothly that some wagging tongues speculated it all had been coordinated ahead of time with the governor, senators and president, a “rescue by arrest.”

TA Ranch today

|

Some 45 cattlemen and Texas shootists agreed to surrender to Van Horn and the 6th Cavalry, but not to Sheriff Angus. Not one had been lost, except to self-inflicted accident. Within several hours, they were mounted on horses and placed in a column bound for Fort McKinney, all the while enduring a different type of barrage – a shower of cold sleet.

The TA Ranch still exists today as a hospitality venue featuring history and working ranch tours, farm-to-table dining and “1880 homestead” lodgings. The original house and barn used by the invaders stand in silent witness to the momentous clash.

Sheriff Angus immediately sought to have the prisoners transferred into his custody so that civil legal proceedings could begin. But he was rebuffed, as Col. Van Horn had orders to keep them under federal control. When Angus then petitioned the governor, he again was advised that the prisoners would stay put at the fort. Nothing more would be done until the governor was convinced that no further violence was in the offing and that the men would be adequately protected.

|

| Fort McKinney (without walls) where the prisoners were first housed Courtesy Johnson County Library |

Mike was among the captured men taken to the fort and detained. None of the prisoners tried any sort of escape. During that time, a rustler-led plot to detonate a bomb under the prisoners’ sleeping quarters was uncovered and thwarted.

The story of the raid spread quickly. Using bright red ink for headlines, the Rocky Mountain News in Denver printed sensational stories, all “malicious” against the cattlemen, recalled Canton. The New York Sun reported that a home guard of 200 armed men were patrolling the streets of Buffalo as rumors were swirling that new squads of invaders were en route from Montana to aid the cattle owners.The New York Sun called it “the war for the extermination of horse thieves” and that the “hired assassins … were to receive $6 a day and $50 apiece for every man killed. It is stated that it cost more than $3,000 to secure Champion and Ray.”

When a news reporter asked an unidentified invader why the expedition failed, the response, as published in the Sun, was:

It was simply met by superior forces. We did not think the whole country would turn against us. We did not want to harm any but notorioius thieves. They [were] circulating the wildest lies. They said that we had cannon, that we were going to poison wells and springs, shoot farmers and cattle bearing brands of small owners; that we were going into Buffalo to hang the Sheriff and shoot down citizens. The Sheriff wouldn't have been overlooked, but we did not intend to harm innocent people. We restricted our shooting at the T.A. ranch because we did not want to wound people who had been forced into fighting us.

|

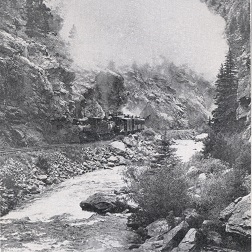

Train carrying the prisoners through Platte Canyon - Malcolm Campbell, Sheriff |

The next nights they made camps at the 17 Mile Ranch and the Ogalalla Ranch, the latter owned by Irvine. After a day of rest, the travelers endured bright sun reflecting off the snow and arrived at Collins Station, frozen, blackened with sunburn, exhausted. The next day they rode on to Brown’s Springs where they tented in heavy snows and high winds. They finally arrived at Fort Fetterman, where they boarded a train bound for the final leg of 11 miles to Douglas.

Eight miles shy of the Douglas destination on Sun., April 24, the decision was made to avoid the inevitable crowd of hostile people at the train station. Instead, they were diverted and waited until receiving an “all clear” to proceed. Once moved into town, the party was received pleasantly by a large enthusiastic and gaping citizenry, which one observer said looked like “a crowd at the zoo which had come to stare at the animals.”

It was here, on the Douglas railroad platform, that Mike’s wife Olive made another appearance, as told in Malcolm Campbell, Sheriff. As the prisoners held their heads out the windows, there “were a number of tearful reunions. Women hurried through the crowd, Mrs. Shonsey among them, and greeted their husbands eagerly, with endearing words often checked by sobs of happiness at having their loves ones restored to safety.”

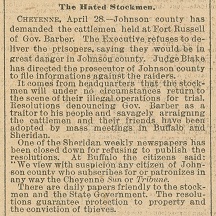

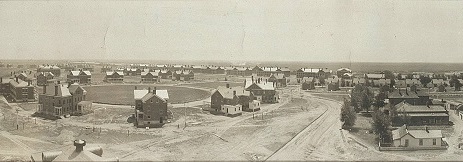

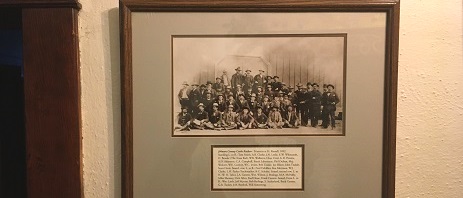

Their train left Douglas and made its way along the Platte River Canyon, finally arriving in the state capitol of Cheyenne. Several hundred people were on hand. The men were off-loaded and taken to Fort Russell, where they were housed in a bowling alley and issued cots for sleeping. And there they remained for several weeks, getting their guns back while waiting for their trial, with the freedom to come and go virtually at will, including fine dining in town. The prisoners posed for a group photograph, dressed in suitcoats and neckerchiefs, an image widely published today with original prints selling at auction for thousands of dollars.

|

| Mike (circled) with fellow prisoners in Cheyenne (Hoofprints of the Past Museum). Fort D.A. Russell, Cheyenne, below, where the prisoners were first housed (Wikipedia) |  |

|

Mike in the prisoner group photo Courtesy Hoofprints of the Past Museum |

The judge in the case, J.W. Blake, of Wyoming’s 2nd Judicial District, was assigned to oversee the trial. The WSGA’s high-powered attorney Willis Van Devanter was engaged as the cattlemen's defense counsel. Because the nature of the proceedings was so novel, Blake raised questions over who was going to pay the enormous court costs and placed the responsibility on the County of Johnson. But it was clear that the county had no budget for such a massive undertaking, meaning a full-scale prosecution of so many defendants just could not go forward.

(Van de Vanter later would be named an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, appointed by President William Howard Taft.)

The prisoners stayed put through May, June and early July, calmly, comfortably and without incident. They finally were transferred on July 5 to a court in Laramie City to undergo a hearing to determine if they could get a fair trial if the matter would be transferred to Johnson County. They rented their own detention facility, the pleasant Hesse Hall hotel, and were given freedom to move about town as long as having a guard as an escort.

At this point in the story, Jones and Walker, the trappers who were spared on the first day’s attack by the invaders, were the only two eyewitnesses to the killings. They would have been sensational on the witness stand had they been called. But they mysteriously left the state, without making any public statements, and with their passage reputedly paid for by the cattle owners.

|

Defense counsel Van Devanter Library of Congress |

On Aug. 1, the cattlemen boarded a train to return to Cheyenne. Upon their arrival, they rented rooms in Keefe Hall, an opera house. Writes O’Neal in The Wyoming Cattle War, “during four months of incarceration, the cattlemen were never behind bars.” Around this time, each one, including the Texas gunmen, received a hefty fee for his services, amounting to hundreds of dollars, and had lodging, equipment, transport and court costs covered by the cattle owners.

During the daytime, they sat in a courtroom and by night were free to come and go. In a rare show of acting out, some trashed a house of prostitution, which ended up costing $300 in repairs. Others took a railroad ride to Denver to attend a meeting of the Knights Templar, and one evening a champagne dinner was held to honor their Texas colleagues. Several of the Texans had drinks one evening with prosecutor John M. Davidson, who suggested that if they wanted to leave town, no pursuit would be made.

The District Court trial began on Aug. 7 in Cheyenne. The staggering cost continued to be pressed as an urgent matter. Officials from all of the counties where the prisoners had been lodged wanted to be reimbursed. It all amounted to an enormous sum which the County of Johnson could not pay. And even more bills were mounting for continued lodging, food and guards. In fact, Johnson County was described at the time as “practically bankrupt.”

|

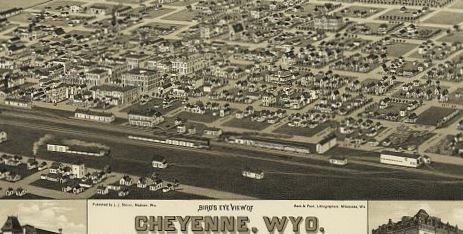

| Bird's eye map of Cheyenne, WY, 1882 - Library of Congress |

And thus on Aug. 10, 1892, three days into the trial, Judge Scott announced that he could not compel the County of Johnson to pay costs it could not afford, and that he had no choice but to release the prisoners for the time being. He set a nominal new trial date in Cheyenne for January 1893. Each man paid bail and left for home. Mercer writes that the public, who had been predicting all along that the prisoners would never be convicted, was utterly disgusted.

Five quiet months passed. When the trial date arrived in January 1893, most of the cattlemen appeared in court, but none of the Texan shootists. More than 1,000 prospective jurors were interviewed, without the trial lawyers arriving on a sufficient number to complete an unbiased group. The County of Johnson was still unable to pay expenses, and without jurors, the prosecuting attorney filed a “nolle prosequi” – official notice to the court that he would “no further prosecute.”

The prisoners’ indictments were dismissed. A motion for them to forfeit their bail monies was rescinded. The trial ended without anyone having been tried for any crime, and while they were not formally acquitted, none could ever be arrested again for the killings of Champion and Ray.

|

| Witnesses from Johnson County who traveled to testify in court Courtesy Malcolm Campbell, Sheriff |

“And Johnson County has never trusted Cheyenne since,” quips Hanson.

In August 1893, President Harrison issued a proclamation exercising his continuing jurisdiction over the matter. He writes:

Whereas, by reasons of unlawful obstructions and assemblages of persons it has become impracticable, in my judgment, to enforce by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings the laws of the United States… the United States marshal, after repeated efforts, being unable by his ordinary deputies, or by any civil posse which he is able to obtain, to execute the process of the United States courts; Now, therefore, be it known that I … do hereby command all persons engaged in such resistance to the laws and the process of the courts… to cease such opposition and resistance and to disperse and retired peaceably to their respective abodes…

Writing in his Banditti book, Mercer rebuts the president’s proclamation, snapping that “No more infamous document ever issued from official pen.”

No greater outrage was ever perpetrated upon a long-suffering people than is here ruthlessly thrust upon all of Wyoming’s citizens. The statements made in the “whereas” were absolutely false in every line. They were lies, pure and simple… How came it, then, that the president of this great country should descend to the level of a blackmailer, and by an official act proclaim to the world that the good people of an entire state were engaged in resisting the law? There is but one explanation – the statements in the petition to Acting Governor Barber had been presented to him as the truth, and he had been deceived by senatorial representatives into believing them. It was the influence of the old Cheyenne cattlemen’s ring permeating official ranks from the policeman on his beat up through all the gradations to the White House in Washington.

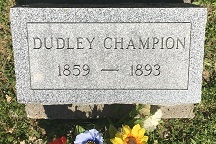

Dud Champion - Johnson County Library |

After the ordeal, which had consumed nine months of his life, Mike returned to home and Olive and went back to work for Western Beef. But the ripples of the War had not fully ended, igniting once more in gunfire and death.

Champion’s brother Dudley had been heard making general threats about wanting to kill the invaders to avenge his brother’s slaying. On the fateful day of May 23, 1893, working on a roundup, he rode into a camp about 20 miles northeast of Lusk, WY and began talking with a group of cowboys. In a great irony of history, Mike arrived at this camp about the same day, with a trail herd heading north. For a time, “pleasant conversation was carried on between the entire party,” writes Mercer. But then something sparked, a flash of fear or anger among Mike and his rival’s brother.

In a typed manuscript by Dr. William A. Hinrich of Douglas, WY, recounted the brief exchange of words:

“Hello Mike.”

“Hello, Dud. I heard you threatened to kill me on first sight.”

“NO! Hold up, Mike!! I never said no such ‘damed’ thing!”

In Hinrich’s account, Mike reached for his gun, then lowered it a bit, but saw Dudley’s hand moving to his own revolver. Mike shot first and hit his mark. Dudley fell to the ground, and when trying to shoot from a prone position, was hit by two more Shonsey bullets.

As he lay dying, Hinrich said, Dudley told onlooker David D. Mathews to “Take my six shooter and tell the boys that Mike Shonsey killed me.”

|

| Cattle near Lusk, WY, where Mike shot and killed Dud Champion Library of Congress - photo by Arthur Rothstein |

|

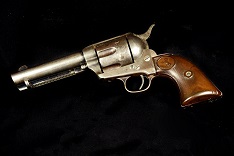

Mike's Colt .45 revolver Courtesy Wyoming State Museum |

“No. He broke my back.”

“What was the matter?” Matthews asked, regarding why Dudley had not fired.

“I can’t cock it,” Dudley said of his pistol. “I can’t cock it. I can’t cock it.” He died within minutes. Says Hanson, “The boys looked at his pistol. It was so full of dirt that it would not cock.”

Who made the first move has never been resolved. Mike called it self-defense. Others said he had been the aggressor.

A reporter for the Davenport (IA) Morning Democrat wrote that Dudley had “made a movement as though to shoot, but was not quick enough.” Author Smith takes the opposing view, saying Shonsey had fired in cold blood. In response to Dudley’s words “I can’t cock it,” Smith quipped that it “does not sound like a man deliberating a killing.”

But what was clear was that another Champion was dead, and that Mike had done the shooting. He immediately rode into Lusk to turn himself in. He was jailed and brought to testify before a coroner's inquest. He told the jury that Champion had drawn his revolver first and that he himself had only been acting in self-defense. With no other evidence, he was released. He boarded a train for Cheyenne, arriving at midnight.

The next morning, Mike left the employment of Western Union Beef, either voluntarily, or not. He then bought a railroad ticket headed south, bound for Colorado, to take a job at the ranch of his old friends, the Hords. The rumor mill hinted that he had fled to Mexico. But back in Lusk the next day, witnesses came forward with an opposing view of the shooting. Mercer states that:

…it was claimed that Champion had made no gun play and that his killing was unprovoked, cold-blooded murder on the part of Shonsey. But the information came too late – the murderer was flying southward and out of reach. Thus was added another crime to the long list chargeable to white cap influence.

Willow Grove Cemetery, Buffalo

|

Counters Hanson, “He probably left Wyoming to avoid ‘lead poisoning’.”

Mercer’s Banditti relates a story about Mike’s departure from Wyoming. He claims that Baxter, as head of Western Beef, and dismayed by the depletion of local grasses, made the decision to move the cattle to Montana “in hopes of securing a better range.” In the fall of 1892, months after the raid, the herd was gathered and some 2,000 unaccounted for cattle allegedly were among them. Admitting that he had no direct proof for the allegation, Mercer blames Mike and his boss as the culprits of their thinning herds instead of the greedy hands of rustlers and ranchers. He writes speculatively that:

Some persons have been uncharitable enough to suggest that the general manager [Baxter] and the range foreman [Mike] had entered into a conspiracy and “put up a job” on the company for their personal pecuniary benefit, namely, anticipating, and perhaps urging the removal of the herd, they had “doctored” the tally sheets so as to show two thousand head less than the real number. Then, when the gather was made, if they found all the books called for, less, say two or three hundred, they could buy the remnant for a few hundred dollars – less than half of the market value of the shortage, for it costs nearly all the value of the tailings of a herd to gather it – and thus have a two-thousand herd of their own. But the little unpleasantness of the invasion made the climate of Johnson county unhealthy for Messrs. Baxter and Shonsey, and the cattle gathering had to be done by cowboys not in the deal.

~ Getting on with Their Life’s Work ~

The first year of the Shonsey marriage was exceedingly difficult, but their union held fast. Mike and Olive were together over the span of 14 years until cleaved apart by death. With him no longer facing blame in the Dudley Champion death, they settled in Central City, CO in June 1893 at the home ranch of the friend who had brought him to cattle country in the first place, Michael Hord. Nearly five years later, in March 1898, they migrated to the Nebraska ranch of Wells & Hord Cattle Company, at the town of Clarks, where Mike became employed as manager. This ranch became one of the larger ones in the country, producing up to 20,000 head of cattle in a single year.

The Shonseys eventually acquired the Howard Crill ranch, raising grain and feeding thousands of cattle in a good year.

|

| Greetings from Clarks, Nebraska |

Together, the couple bore four children -- John Harold, Michael Gerald, Thomas Benton and Margaret (Shonsey) Masters.

When the federal census enumeration was made in 1900, Mike's occupation was as a stock feeder. They had four boarders in the household at that time. Over the years, Mike had many dealings with Charles C. Carson, son of the famous Indian scout Kit Carson, who also was in the cattle and ranching business as well as in traveling circuses. News reports for 1902 show that Mike and Olive returned to his old home in Caledonia, OH for a visit with kinfolk.

|

Mike in 1954, inscribed - Hoofprints of the Past Museum |

Sadly, suffering from kidney disease at the age of 39, Olive entered Omaha's St. Joseph's Hospital for treatment. She stayed for nine weeks but there was no cure, and she died on Nov. 11, 1905. The Central City (NE) Record reported that "For days past her condition has awakened alternate hopes and fears, as she rallied or became worse. At one time her health improved so that it was though she would soon recover, but it was not to be..." An obituary in a Nance County newspaper reported that she “was said to have been one of the most charitable women in the state, and had fed and clothed hundreds of poor children." The Clarks Enterprise added that she had been "Large hearted, generous, hospitable, unconventional [who] counted her friends by the score... Called from life when it seemed that she was most needed, her demise is exceedingly sad."

Mike outlived his first bride by almost half-a-century. After a grieving period of about a year, he entered into marriage with Hannah Lillian Harris (1867-1956) of Columbus, NE.

Mike made news in 1907 for his roping prowess at the first annual Merrick County Agricultural and Fair Association. Clucked the Central City Record, "The steer-roping by Michael Shonsey on Friday attracted about everybody on the grounds. The steer was roped and thrown in one minute and twenty-three seconds, which is twenty-three minutes and one second quicker than the Record editor would have engaged to get the rope around the steer's horns."