| Home |

|

Lucinda M. (Miner) Davidson |

|

Oak Hill Cemetery |

Lucinda M. "Lue" (Miner) Davidson was born in 1843 in Columbus, Franklin County, OH, the daughter of Francis and Myra (Jordan) Miner. She was a pioneer settler of Illinois, and her husband was a prominent newspaper editor who knew Abraham Lincoln, contributed significantly to his region's economic development, and was harshly ridiculed in Edgar Lee Masters' famed book of poems, Spoon River Anthology.

When Lucinda was a young woman in 1854 and 1855, her mother and two sisters died in Columbus, and were buried there. The grieving father and remaining sisters then migrated to Illinois, settling in or near Lewistown, Fulton County.

|

|

|

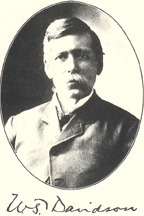

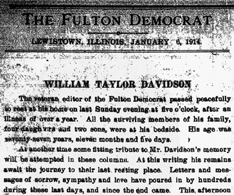

William Taylor Davidson |

On Jan. 24, 1860, in Fulton County, Lucinda married local newspaperman William Taylor Davidson (1837-1915), the son of Isham Gaylord and Sarah Ann (Springer) Davidson, and a native of Petersburg, Menard County, IL.

They had seven children -- Harold Lee Davidson, Mabel Davidson, Bertha B. Davidson, Frances M. Davidson, Lulu Martha Davidson, Nellie Davidson and Maude Davidson. Sadly, daughters Mabel and Nellie died in infancy, and were the first burials in what became the Davidson plot at Oak Hill Cemetery in Lewistown.

William's father was employed as a "minor official" in the Fulton County Courthouse. Much later in life, William said that "As a frail little chap I was much with him during court and from my fifth year was permitted very often to stand or sit near the presiding judge, the first of whom was Judge Stephen A. Douglas. From childhood I was thrilled by oratory rather than music or painting; so I ever haunted the court house to hear the mighty men of the Illinois bar who traveled the circuit sixty to seventy years ago."

At the time of marriage, William was the sole owner and editor of the Fulton Democrat, and with Lewistown as his base, was beginning to make a name for himself statewide in the journalism field. A biographical portrait of William in a local history book said that:

At the age of twelve he had to go to work to keep the "wolf of want" from the log cabin door. From the age of twelve to seventeen he drove his father's team, hauling produce to the Illinois River, either to Havana or Liverpool, with merchandise for his return trips, or hauling building stone and sand to town from adjacent quarries or banks, or hauling coal from nearby mines and wood from the great forests. Little lads of his age in these days can hardly comprehend the bitter cold, the frightful storms, the hardships and dangers this slight boy encountered in these five years. A withered arm and frail physique led him at the age of seventeen (April 3, 1853) to become an apprentice to the printer's trade in Hugh Lamaster's "Fulton Republican" office in Lewistown.

|

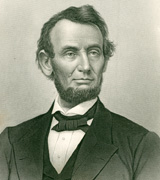

William knew both Abraham Lincoln (left) and Stephen A. Douglas and covered their famed debates in 1860. |

|

|

|

William's bio - Fulton County history |

William's mother, Sarah (Springer) Davidson, was well acquainted with many of the political and religious leaders in Illinois during the time William would have been reaching adulthood. According to one newspaper article, "she became well acquainted with Peter Cartwright and many other notable divines of the Methodist church, who made their home when visiting the circuit. She has often entertained both Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas at her hospital board." The article, circa 1888, claimed that she was "probably the oldest living settler" in the county. William himself directly was involved in writing the news coverage of the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates.

Among the notables William came into contact with during his boyhood and adult years included the following -- he once identified them in a speech on "Famous Men I Have Known in the Military Tract," though many of the names are forgotten today -- Edward Dickinson Baker ("Ned" Baker), James Shields, Peter Cartwright, Hezekiah M. Wead, William Kellogg, Col. Lewis W. Ross, Gen. Leonard F. Ross, William C. Goudy, William Pitt Kellogg, Col. Robert G. Ingersoll, Judge Chauncey L. Higbee, S.S. Brooks and Austin Brooks.

|

|

William's speech, "Famous Men I Have Known in the Military Tract," reprinted in Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society for the Year 1908. |

|

Political cartoon, 1862 |

Of knowing Lincoln and Douglas (whom he preferred of the two), William said: "I would not take one star from the deathless diadem of Abraham Lincoln. He was the gentlest, sweetest, truest soul the earth has known since Christ. His fame fills all civilized lands and grows brighter with the fleeting years. I am only courteously asking [you] to grant to the dead Douglas the fair play and justice he implored in vain..."

A political cartoon of the Democrat, published on April 5, 1862, a year after the outbreak of the Civil War, gloated as follows:

Lewistown

sends Greetings to the Democracy Everywhere!

We have met the enemy,

and they are in their holes!

Niggerism,

Mob-law-ism,

Dark-lantern-ism,

Secession-ism and all the

"isms,"

"cleaned out" most gloriously!

For Lucinda and William's wedding journey, "the pair went on an editors' excursion to the East, where they visited Washington and heard Senator Douglas deliver one of his impassioned, electrifying speeches in the United States Senate on topics then agitating the nation," reported the April 1915 issue of the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, by Supt. John R. Rowland. "In an interview with him afterwards, the 'Little Giant' took the young couple by the hands, warmly greeted them familiarly by their first names, as was his custom with acquaintances, and graciously wished them godspeed."

The book, Portrait and Biographical Album of Fulton County, published in 1890, when William was still active as "the well-known editor and proprietor of the Fulton Democrat, the leading paper of this county, has exercised a marked influence on the affairs of this section of Illinois, and even of the entire State, not only professionally, but as a progressive, public-spirited citizen, and has aided in guiding its political destiny, as well as in guarding and advancing its dearest interests materially, socially and morally."

|

|

Civil War era issues of the Democrat -- Aug. 10, 1861 (left) and April 5, 1862, the latter of which is lighter in density and smaller in width by 2½ inches, perhaps due to a scarcity of printer's ink and newsprint during the war. Below: William's name graces the masthead of the 1861 newspaper. Click for enlarged versions. |

|

|

Lewistown's North Street |

Lewistown's North Street, circa 1909, seen here.

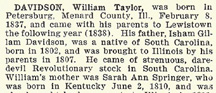

An online history of the Fulton Democrat states that William was "generally recognized as the master force behind the promotion and building of the Fulton County narrow gauge railway, which provided an important transportation link in the days before paved roads and automobiles. The sixty-one miles of three-foot-gauge railroad was popularly known as the 'Pavane' for its winding, twisting pike that extended south from Galesburg to West Havana."

In the shadow of a famous, accomplished husband, Lucinda "was a woman gifted and beautiful -- beautiful both in character and personality," said the Canton Weekly Register, which continued as follows:

Her disposition was of the sweetest and most cheerful. Her light laugh returns to those who knew her, like the memory of music. She was the ideal wife and mother, hopeful in time of trouble and helpful in time of need. Her energies were expended chiefly in the home circle, and at times as her husband's assistant in editorial work; but her sweet influence was as far reaching as it was beautiful and kindly.

|

|

|

Fancy stationery of the Fulton County Narrow Gauge Railway Company |

|

|

|

Lewistown High School |

Devoted to the values of public education, William "was elected Commissioner of Schools for Fulton county in 1863, and did much to rectify the prevailing abuses of school privileges," said the History of Fulton County, in a paragraph-long entry about him.

Seen here, the Lewistown high school building of the early 1900s.

In 1881, William lost an index finger in a freak accident with a cylinder power press, and Lucinda substituted for him in the office until he healed. Noted the Feb. 3, 1881 edition of the Carthage Republican, "The last issue of the [Democrat] paper affords no indication of the recent loss of an index finger from its editor's right hand, the editorials being dictated to, and some of them doubtlessly written by the editor's wife, a smart capable lady who is equal to an emergency calling for her prompt and brainful work. The Democrat is a marvel of county journalism."

The full text of the Republican and other related articles is on the IllinoisAncestors.com website.

~ Bitter Enemies ~

|

|

William (left) was skewered in Spoon River Anthology by his nemesis, the famed poet Edgar Lee Masters. |

|

First edition |

For as much as he was a powerful force for good in the community, William had his enemies, and bitter ones at that. One such antagonist was Hardin W. Masters, a local political activist and alcoholic imbiber who clashed with the anti-liquor William over temperance issues. William also is believed to have blocked Masters' nomination for Congress. Masters' son, Edgar Lee Masters, who grew up to become a world famous poet and author, savaged William in poetry and books.

|

|

|

From Spoon River Anthology |

John E. Hallwas of Western Illinois University, who has extensively studied and annotated Masters' writings, states that Masters' "first published poem, 'The Minotaur: Bill Davidson,' (1884) was a satirical attack on the man." As well, Masters describes the conflict between his father and William in the 1937 novel, The Tide of Time.

Masters authored a classic book of American satire, Spoon River Anthology, published in 1915, which he used as a tool to criticize the myth of moral superiority in small town America. In this work, he questioned the motives of civic and business leaders such as William. One critic of the book has summarized it as a collection of dramatic monologues by several hundred townspeople, as if spoken from their graves, giving testimony to "shocking scandals and secret tragedies."

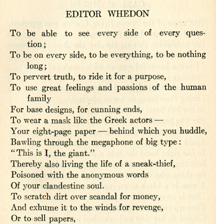

In the Anthology poem "Editor Whedon" (reprinted here), widely acknowledged to be a pseudonym for William, Masters writes of William's willingness "To scratch dirt over scandals for money, And exhume it to the winds for revenge, Or to sell papers, Crushing reputations, or bodies, if need be..."

Masters also subtly ties his criticism of William to the dirty imagery of sewage flowing from the village, empty cans and garbage dumps, and hidden abortions.

The manuscript of the Anthology cannot be had. Book collector bookseller and university librarian David A. Randall, writing in Dukedom Large Enough, says that he knew Masters and was a "great admirer" of the volume. "I once asked him about the manuscript and he replied that it simply didn't exist. Many of his poems had originally appeared in Reedy's Mirror, and the copy sent to the printer consisted mainly of clipped printed material."

|

|

Edgar Lee Masters' handsome home in Lewistown |

~ Lucinda's Untimely Passing ~

|

|

|

Canton Weekly Register, 1893 |

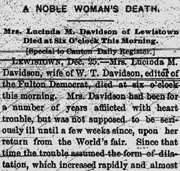

In December 1893, despite the fact that she had suffered with heart trouble for several years, Lucinda traveled with William to Chicago to attend the World's Fair. Upon returning home, she became seriously ill, and "the trouble assumed the form of dilatation, which increased rapidly and almost without interruption until death resulted," reported the rival Canton Weekly Register newspaper. "She died as a child going to sleep."

Lucinda passed away at the age of 50 on Christmas Day 1893. Her death was front-page news. She was laid to rest in Section E of the local cemetery. The Davidsons had been married for nearly 34 years.

Said Rowland in his 1915 Journal article, "Very often in later days Mr. Davidson referred with deep feeling to the unselfish love and loyal devotion of this blessed woman who uncomplainingly shared the struggles and triumphs of his earlier manhood, and continued his discreet counsellor, congenial companion, and faithful helpmeet till her departure left him desolate."

In an article headlined "A Noble Woman's Death," the rival Canton Weekly Register expressed that "earnest sympathy of all will go out to Editor Davidson and family in this, the dark hour of their affliction. Worlds have, perhaps, but an empty meaning under such circumstances, and yet who can doubt the earnest with which words of condolence are spoken?"

|

William's 2nd wife |

~ A Second Marriage ~

On April 3, 1895, after just a little more than 14 months alone, William married his second wife, Margaret Gilman George (1870-1897). She was the beautiful and talented daughter of Benjamin Y. and Adeline (Gilman) George of Elmwood, IL, who had been born in Columbus, Boone County, MO. The ceremony took place at the home of Margaret's grandmother in Dallas, TX.

William was 32 years older than his bride, and ironically, she had once been the companion of his hated rival, Edgar Lee Masters.

The Davidsons went on to have one son, William Gilman Davidson, born in 1896.

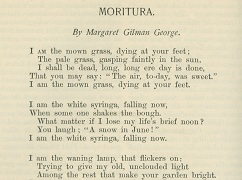

As the daughter of a prominent clergyman of Lewistown at the time, Margaret grew up in a home with a large library. Said biographer Rowland, she "was a woman of lovely individuality and brilliant intellectual endowments. A writer of exquisite verse, Miss George found ready acceptance of her poems by The Century Magazine, The Youth's Companion and other high-class periodicals." A publication written some three-plus decades after her death noted that:

From a little child Margaret showed a love for the beautiful that was most remarkable. As she grew up, her health was so uncertain, that she was unable to attend school regularly, so her father gave her training at home. She became a thorough scholar in the best of English Literature and was also a fine historian. Later, she spent two years specializing in Greek and Latin at the State University, living with her grandparents.... She developed such marked ability that she attended the fine Art School in Kansas City for several seasons.

One of her works, "Moritura," was printed in Scribners Magazine in October 1893 and is reproduced in An American Anthology, 1787-1900, edited by Edmund Clarence Stedman. Others were "The Looked-for Man" in The Century Magazine (March 1891), "Wind Wishes" in Wide Awake (November 1892) and "It's An Ill Wind" in Munsey's (May 1893). Included among her other poems were "Brief Biography" and "Paneled in Pine" as well as "Here I Lie" -- "Shrived" -- and "Prisoner." Her poem "Where Love Is Lord," printed in New Lippincott, was reprinted in the May 25, 1901 edition of The Corrector newspaper of Sag Harbor, New York.

|

|

Above: April 1, 1897 edition of The Youth's Companion, containing Margaret's poem "The Picture." (She died nearly seven months after this was published.) Below: the Aug. 4, 1894 issue of The Critic with her poem "Wakened." |

|

|

|

|

Bio of William's nemesis |

Ironically, Margaret's former beau, Masters, had broken off their romance in 1889, some six years before her marriage to William. This greatly added to Masters' harbored resentment. A fictional account of their doomed courtship is described as "Anne" in Masters' autobiography, Across Spoon River. He also is said to have fictionalized their love affair in his 1923 novel, Skeeters Kirby. Margaret is characterized in Masters' Spoon River Anthology poems entitled "Caroline Branson," Amelia Garrick," Julia Miller" and "Louise Smith."

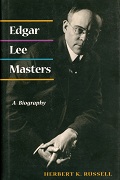

The intense rivalry between William and Masters, and the poet's lasting affection for Margaret, despite his own marriage to someone else, are described in the 2001 book, Edgar Lee Masters: A Biography, by Herbert K. Russell (University of Illinois Press).

She and William jointly authored a novel, The Yellow Rose: A Wilderness Honeymoon, a tale about Captain William Phelps and his wife Caroline of the 1830s. Phelps was a steamboat captain and early trading partner of Native Americans living in Eastern Iowa and Illinois. It first appeared on the pages of the Fulton Democrat in 1892. The volume was published in 1929 by C.A. Woodruff Publishing Company of Little Rock, AR, and in 1977 reprinted by the Amaquonsippi Chapter of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Minerd.com is in the process of compiling a bibliography and archive of her original published works of authorship, with the aspiration of being as comprehensive as possible.

Sadly, the second marriage only lasted a little more than two years, ending in Margaret's untimely death. She had long suffered from a heart condition resulting from a childhood illness. She passed away suddenly a year after giving birth, on Nov. 27, 1896.

|

|

Above: the March 15, 1890 edition of Good Housekeeping, containing Margaret's poem, "Midnight Musings." |

|

|

|

Above: "Moritura" in Scribner's Magazine, October 1893, later republished in Edmund Clarence Stedman's An American Anthology. |

|

|

"The Looked for Man," The Century Magazine, March 1891 |

|

Obit in William's own newspaper |

She is said to have been reading the Bible at the moment of her death. Her husband came home from work at lunch to find her lifeless, bearing a pleasant smile, and with the Holy Book resting in her lap. She was placed into eternal rest in the Davidson family plot in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Her passing at the tender age of 27 left William a widower for the second time in just four years, and a baby son who never knew her.

~ William's Final Years as a Widower ~

|

|

|

Oak Hill Cemetery |

William survived alone for nearly two decades. His daughter Frances worked without pay in the newspaper office during that time, although after his death, she collected $1,310 in back pay for five years and two months' worth of work, valued at $5.00 per week.

William passed away in Lewistown on June 3, 1915, at the age of 78. He was buried between his wives in Lewistown. He had served as editor of the Democrat for more than half a century at the time of his death, and was widely mourned in the community.

The news naturally was top of the headlines and the lead editorial in the Fulton County Democrat. Tributes poured in from all over the state.

In his will, William bequeathed his entire newspaper office and plant to his daughters Frances and Maude, "including all furniture, presses, types and all other fixtures, tools and implements, used in publishing the Fulton Democrat, together with its subscription lists, accounts and good will," he wrote.

Over the years, the newspaper faithfully was continued by daughters Bertha, Frances and Martha, and by son Gilman, who assumed the role of publisher and editor. It continues to be produced today by one of Gilman's nephews by marriage.

The full-text of William's biography in the Portrait Album is published online by RootsWeb.

|

|

Row of Davidson graves in Lewistown, with William between his wives at right |

~ Posthumous Honors ~

|

|

|

Booklet naming Margaret |

After Margaret's death, one of her poems -- "Moritura" -- was selected for inclusion in An American Anthology, 1787-1900, compiled by Edmund Clarence Stedman. A note in the book stated that at the time, William "has in view a memorial collection of her poems."

A related obituary in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine noted that Margaret's "poems have often appeared in Lippincott's.... She had a happy gift of verse, and her productions deserved to be more widely known. So far as we are aware, they have not been collected."

In 1932, a small figurine of Margaret was made by Minna (Moscherosch) Schmidt of Chicago among 129 similar miniatures of Illinois women who shaped Illinois history in "some special way." The figurines were "deposited in the Illinois State Historical Library, where they are on display at all times," reported the library. "They are dressed in the costumes of the periods which they represent, and attract much attention." A catalogue of the items was published, in soft brown covers, entitled Brief Biographies of the Figurines on Display in the Illinois State Historical Library. The whereabouts of the figurines today are unknown.

|

|

|

Gilman Davidson |

~ Continuing the Fulton County Democrat ~

William's only son from the second marriage, William "Gilman" Davidson (1896-1967), seen here, was born in 1896. He served as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army during World War I.

After the war, he returned home to Lewistown and worked with his sisters at the Fulton Democrat, and eventually became principal editor beginning in 1926.

On Oct. 25, 1945, in Greenville, MS, at the age of 49, Gilman married Neta Lyons (1905-1977), and they resided in Lewistown. The Davidsons had no children, but employed Neta's nephew, Robert L. Martin, to be its editor, with Gilman serving as associate editor.

Gilman died at the age of 71 on Sept. 4, 1967 at the Mason District Hospital in Havana, IL. In a front-page obituary about Gilman, the Democrat said:

He was one of the most forceful and irrepressible of all the editors of the state. His editorials were fearless and his paper reflected this characteristic of his nature. He was a prominent member of the Democratic party who fought the things that he regarded as wrong with virility and courage. He did not mince words. He was usually inclined to call a spade a spade. This made life interesting and picturesque in Fulton County. Gilman put a great deal of character into what he wrote. On the whole he stood for good ideals and a clean and friendly community. In many directions he was an influential power.

|

|

Gilman Davidson's obituary, Sept. 6, 1967 |

Neta outlived Gilman by

a decade, and passed away in 1977 at the age of 72. They are buried together in

the Davidson section of Oak Hill Cemetery in Lewistown.

Neta outlived Gilman by

a decade, and passed away in 1977 at the age of 72. They are buried together in

the Davidson section of Oak Hill Cemetery in Lewistown.

|

The Davidsons' legacy today |

Seen here, the Fulton Democrat building as photographed in October 2007. Today, the newspaper is published by Gilman Davidson's grand-nephew and niece, Robert and Wendy Martin.

Minerd.com wishes to express grateful appreciation to the Martins for their many kindnesses and gracious sharing of information.

~ For More Reading on William Taylor Davidson ~

-

The Spoon River Country, by Josephine Craven Chandler (1977), reprinted from the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 14, Nos. 3-4.

-

History of the Fulton County Narrow Gauge Railway, by E.W. Mureen (August 1943).

-

"William Taylor Davidson," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (April 1915), Vol. 8, No. 1, by Supt. John R. Rowland.

-

History of Fulton County, Illinois.

-

Portrait and Biographical Album of Fulton County (1890)

-

Illinois Family Newspapers - Celebrating Illinois History (2005), by the Illinois Press Association.

-

Robert Lee Masters: A Biography - by Herbert K. Russell, University of Illinois Press (2001).

-

Spoon River Anthology: An Annotated Edition, edited and with an introduction and annotations by John E. Hallwas, University of Illinois Press (1992).

-

The Tide of Time, by Edgar Lee Masters (1937).

-

Across Spoon River, An Autobiography, by Edgar Lee Masters ( ? ).

-

Skeeters Kirby, by Edgar Lee Masters (1923).

|

|

Two books of more recent vintage, mentioning William -- American Narrow Gauge Railroads (left) and Dime Novel Desperadoes. |

|

Copyright © 2006-2014, 2020 Mark A. Miner |

|

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln originally published in Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln (New York: North American Publishing Company, 1886), courtesy of the Heinz Bros. & Co. collection. Portrait of William A. Douglas originally published in Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1939), authored by Carl Sandburg. Spoon River Anthology manuscript reference from Dukedom Large Enough (New York : Random House, 1969, by David Anton Randall. |