|

|

Jemima

(Minerd) Burditt |

|

Jemima Burditt |

Jemima "Mime" (Minerd) Burditt was born in March 1839 in New Rumley, Harrison County, OH, the daughter of Samuel and Susanna (Hueston) Minerd.

She is acknowledged as one the earliest settlers of Wood County, OH, and her husband was a Civil War veteran who was both wounded in action and a prisoner of war.

As a girl, Jemima moved with her family from Harrison County to Tontogany, Wood County. During the winter of 1859-1860, Jemima met her future husband, William J. Burditt (1838-1911). He stood 5 feet 6 inches tall and had a light complexion. They courted for nearly two years before marrying.

Jemima

is seen in the oval portrait here as a young woman

In young womanhood

On Aug. 18, 1862, at her parents’ home, Jemima and William were married, by the hand of justice of the peace Edwin Fuller. Fuller later recalled that the ceremony was marred by the poor behavior of Jemima's mentally ill brother, Alpheus Minerd. Just before the ceremony was to begin, with Alpheus missing, his:

… father and some of the others present went out to find Alpheus … and to call him in to witness the marriage…. The father and the others returned without Alpheus, who was in an out-building, and who refused to come in. The father’s troubled face caused me to ask him what the trouble was. He, the father answered me that Alpheus refused to come into the house and was secreted. I asked the father what was the matter of the boy. The father said that the boy was not right in his mind, that he had spells of insanity, that he was deranged, that he, the boy, caused the family a great deal of trouble, that he often hid himself away, that it was often difficult to find him, that they often feared him.

The Burditts went on to have three children – William J. Burditt Jr., Isabelle "Belle" Robinson and John Minard Burditt.

Just four days after his wedding, with the Civil War raging, William enlisted in the Union Army at Monroeville, OH on Aug. 22, 1862. He was assigned to Company D of the 123rd Ohio Infantry.

|

2nd Winchester battlefield |

William and the 123rd Ohio fought in the Second Battle of Winchester, VA, which lasted three days. On the second day, his hearing was damaged by the explosion of a shell during a heavy Confederate bombardment, which occurred on a farm called Glen Burnie. (The battlefield, still privately owned, is seen here circa 1989.) At about 4 pm that day, Union General Robert H. Milroy ordered the 123rd Ohio, along with the 122nd Ohio and 12th West Virginia Infantries, to launch an attack. However, the enemy gunfire was so heavy that the regiments could not advance, and Milroy ordered them to retreat and march into Fort Milroy, near the town.

Thomas H. Maloney, a private with the 123rd Ohio, later wrote that "When the enemy made a charge on our line and they shelled us at the same time one shell lit close to [Burditt] and burst, causing him to be varry hard of hearing." George D. Acker, a second lieutenant with the regiment, reported that:

...the enemy commenced to shell us from different points, about 3 or 4 o’clock p.m. While marching to the fort a shell exploded on the ground near the right flank of the company, so near that it threw dirt over the boys in the vicinity of the explosion…. The fight lasted all night …

The townspeople of Winchester, who largely sympathized with the Confederacy, watched the bloody battle with mixed feelings. One resident, Cornelia McDonald, kept a diary and wrote:

It seemed as if shells and cannon balls poured from every direction at once. One battery from the hill opposite our house rushed down and through our yard, their horses wounded and bleeding, the men wounded also, and pale with fright. ... Ambulances were backed up to let out their loads of wounded, and horses reared frantic with pain from their bleeding wounds, Some were streaming with blood, and looking wild, and their poor eyes stretched wide with pain and fright .... All the while the batteries thundered, the booming of cannon, the screaming of shells (who that has ever heard that scream can ever forget it?)

Overnight, Milroy decided to evacuate his troops from town. In the wee hours of the morning of June 15, 1863, the 123rd Ohio and many other regiments tried to escape via a ravine north of town, only to be cut off and captured en masse at Stephenson's Depot by Confederate cavalry.

William and 3,300 fellow prisoners of war were forced to parade through the streets before beginning their long march to Richmond, VA. Mary Lee, another local diary keeper, walked beside the long blue column, observing that the hated Yankees were "driven like a flock of sheep ... through the streets they had profaned with their presence & before the citizens whose lives they had made a burden.... Some few of the most impudent of [them] ventured to call out that they would be back soon."

After arriving in Richmond, a 95-mile march, the prisoners were first held at Libby Prison. They then moved to a prison on nearby Belle Isle, where they stayed about a month. Conditions in the Richmond prisons were deplorable. In William's own words, he became ill when he "incured sunstroke by being overcome with heat and over exertion." Comrades J.J. Bowman and C.A. Doe later testified that "We were close by and seen [William] fall to the ground and carried into the enclosure...."

|

|

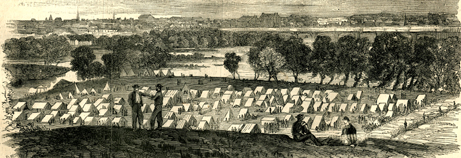

Union POW prison tents at Belle Isle on the marshy falls of James River, the Confederacy's largest military prison, surrounded by a stockade |

He was paroled at City Point, VA on July 14 and then reported at Camp Parole, MD a day later. In Sept. 5 of that year, he was at Camp Chase, OH. The following year, when the regiment was stationed in Sandy Hook, MD and Little York, PA, on July 8, 1864, William was treated for illness.

|

Surgeon's sketch of William's battle wound |

On April 7, 1865, just two days before the war ended, William was shot in the thigh after being captured in a battle south of Farmville, VA. He and the 123rd were sent from Berksville Junction to destroy High Bridge over the Appomattox River. According to a report, "before reaching there was attacked by the enemy and after 2 hours fighting was forced to surrender…" In his own words: "I was taken a prisoner on the eve of the 6th of April 1865 … and while the enemy were on the retreat through Farmville and just after passing through the town the enemy made a halt and then and there received said wound… [a gunshot] in right thigh ball passing through the thigh bone."

Thomas G. Carlisle, of the regiment, recalled that William was shot when "a body of cavalry dashed up within a few rods of the Union prisoners then in the hands of the enemy."

A surgeon's sketch of the bullet hole is seen here, looking from behind. He was “first treated by Reble Surgeon and then fell into the hands of our men and sent to [Point of Rocks Hospital] without ever seeing any of my regimental surgeons.” He was held until the evening of the 9th. He remained in the hospital for several weeks until the end of the month, when he was transferred to the US Hospital at Portsmouth, near Norfolk, VA, remaining there until he was discharged on June 17, 1865.

When the war ended, William returned home to Fostoria, Seneca County, OH. His sister, Hannahretta G. (Burditt) Flint, who later lived at Kinderhook, MI, recalled that “I was at home with our parents when he came home from the war. I take the date from an old diary. He came home on crutches…” Sister Phebe A. (Burditt) Dale, of Lake City, MN, verified the story, adding that he “was partially deaf, putting his hand to his ear while in conversation…”

Immediately upon being discharged from the Army, William began receiving a small military pension of $6 a month in compensation for his wound.

In the fall of 1865, the William and Jemima relocated to Branch County, MI. Daughter Belle was born there in 1866. Then, in 1867, they moved to near Tontogany. For a short period circa 1879, the Burditts returned to Fostoria, about 30 miles from Tontogany, where William was employed in “milling.” Around that time, he fell from a scaffold and injured his left arm.

|

Gordon’s 1886 Atlas of Wood County |

In 1871, William and his brother in law Jacob Minerd jointly purchased a 20 acre tract, two miles north of Tontogany, from father-in-law Samuel Minerd. The Burditts are thought to have remained on this farm for many years. The farms are clearly marked in Griffing, Gordon’s 1886 Atlas of Wood County, Ohio.

Among the Burditts' neighbors in Tontogany was Nevin J. Custer, brother of famed and ill-fated General George Armstrong Custer, who was killed at the Battle of Little Big Horn. In fact, Jemima's sister Rebecca, and Custer's brother Thomas, produced a child out of wedlock, Thomas C. "Tommy" Custer. One of Nevin Custer's farms can be seen in the lower right-hand corner of the 1886 map.

In addition to milling, William was a local bridge builder. The Index to Commissioners Journal of Wood County lists many contracts that he and Jacob Minerd received over the years. They built simple-span structures over local creeks as well as large man-made ditches that drained surface water from the flat farm fields. These included bridges in the towns or townships of Tontogany, Freedom, Pemberville, Milton, Weston, Bloom, Jackson and Washington. The Index covers the years 1895 to 1901.

Wood County Fair |

Jemima gave birth to her first two children early in the marriage, in 1862 and 1866. Then, in 1876, when she was 37, she bore her last son, 15 years after her first.

She was a skilled seamstress. In March 1901, she is known to have received a request from Clara Streeter Bobel to weave a carpet.

By 1901, a family member observed, the Burditt farm was "managed and worked by his son." While it's not known whether the Burditts actually attended, the Wood County Fair (seen here in a rare old postcard view, circa 1908), must have been a major annual draw for local farming families.

As he aged, William suffered from heart trouble and pain in his left side. He also had varicose veins in his wounded leg, as thick as a pencil. Friends considered him two-thirds disabled from being able to labor for a living. He once wrote:

I have a great deal of pain in my leg from wound. I suffer the most however from pain in the head, especially when in a warm room or during hot weather. My heart also troubles me greatly. I can’t take any exercise without becoming very “short of breath.” I can do but little labor of any kind.

|

|

Tontogany's East Main Street -- note "Lumber and Coal Office" |

|

Jemima, daugher Belle and grandson Ross |

Jemima is seen at here in a three-generation photo of that era, with daughter Belle Robinson and grandson Ross Robinson.

Neighbor Thomas Stone said that "He worked for me or tride to work but was overcom with the heat and had to go home." He also is known to have labored on the farms of Alexander McCombs and George Vollmar. During a medical examination in 1893, a physician wrote: "This man appears anemic and very poorly nourished."

In 1908, desiring to obtain an increase in her husband's pension, Jemima asked Tontogany Mayor Dr. A. Eddmon to assist. In his correspondence, the Mayor sympathetically referred to her as “this poor invalid lady…” He also examined the Burditt family Bible, and wrote this summary of it for the government, to prove William's age:

Said Bible was published by Phinney & Co. at Buffalo N.Y. in the year of 1853. I find a Birth Record in the said Bible and the first one is the soldier’s father who was born in 1806, I find the name of [the soldier] as William James Burditt born on the 27th day of March 1838… No erasures appears in the said records.

|

Bowling Green Sentinel |

William died on April 28, 1911, at the age of 73. The details of his death are not known.

Jemima lived for another three years, and passed away at age 75 on July 27, 1914. Her obituary in the Bowling Green Daily Sentinel Tribune said that she suffered from hardening of the arteries and had been in a coma for several days.

William is mentioned in Volume 2 of the 1998 book, Wood County's Role in the Civil War, published by the Wood County Chapter of the Ohio Genealogical Society.

~ More on the Second Battle of Winchester ~

McDonald, Cornelia. A Diary with Reminiscences of the War and Refugee Life. Nashville: Cullom & Gertner Co., 1934.

Lee, Mrs. Hugh H. Diary, Typescript. Handley Library, Winchester, VA.

Miner, Mark A. "First Fight, First Blood." Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society Journal (Volume IV, 1989).

Copyright © 2002, 2006, 2010-2011 Mark A. Miner