|

Marietta

(Minerd) Crosby |

|

Lewis and Marietta |

Marietta (Minerd) Crosby was born in Feb. 1870 in Bridgeport, near Mount Pleasant, Westmoreland County, PA, the daughter of Eli and Mary Ann (Baer) Minerd.

On Feb. 15, 1887, when she was age 18, Marietta traveled to Scottdale, Westmoreland County, to marry her beau, 21-year-old Lewis G. Crosby (Sept. 8, 1867-1931), the son of Hiram and Delilah (Boyer) Crosby.

Marietta's dark wedding dress, fashionable in its day, is seen here.

|

Marietta's wedding dress |

The Crosbys made their residence near Bridgeport and in the coal mining town of Buckeye over the years.

The couple produced a family of eight known children -- Lucinda Kelly, Lloyd M. Crosby, Maria "Mattie" Bowman, James Crosby, Alice Fehr, Richard Eli Crosby, Eathol M. Crosby and Francis Yelaine Crosby. There was a 22-year difference between the oldest and youngest.

Lewis worked as a master mechanic for more than four decades at the Buckeye and Morewood coal mines of the H.C. Frick Coke Co., part of the Carnegie Steel Company, later merged into U.S. Steel Corporation. His son Francis once said, "All Dad knew was eat, sleep, work."

Located near Mount Pleasant, the Morewood Mine frequently was the scene of sometimes deadly violence in disputes between management and labor over wages and, ultimately, the right of unions to organize at the works. Morewood made national news in April 1891 due to labor unrest, with the company pitting Welsh and Irish against Hungarian and Slav as replacement workers in a strike. Lewis would have been age 21 at the time, and in his sixth year of Frick employment.

|

Frank Leslie's Illustrated, 1891 |

Reported Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, the "mines, dwellings, coke-ovens and company property are situated in a narrow valley not more than 1,000 feet wide, with rolling hills on either side. These works were the first to introduce Hungarian and Slav coal miners into Pennsylvania, and difficulties between the employers and employés have frequently occurred." Continuing, reported Leslie's:

The

recent troubles in the coke regions of Westmoreland County, Pa., were the

natural results of the presence in that district of about five hundred Hungarian

and Slav coal miners, coke drivers, and other employés , who have been drawn

thither from time to time until the Welsh and Irish have been almost entirely

driven out... The striking employés of the Frick Company's works discharged

themselves, and the owners of the works thereupon employed other men to take

their places. Then the strikers undertook to drive these men away and to destroy

the property of their employers. In pursuance of their purpose they marched in

large numbers, in the darkness of the night, against the company's works, many

of them being armed with guns and pistols, while others carried sticks and

various weapons. Upon their approach they were warned to desist from their

aggressive purpose, but pushing forward, they were met with a sharp volley from

a body of deputy sheriffs armed with Winchester rifles. The result of this was

that seven of the rioters were instantly killed and a large number wounded.

Three of the latter subsequently died. The killing of the assailants produced a

profound sensation among the working people of the district, and it was found

necessary to call out two regiments of militia, the Governor of the State very

properly maintaining that he had nothing whatever to do with the merits ... but

that it was his duty to maintain and enforce the laws of the State at all

hazards.

For a day or so the coke region presented a very

warlike appearance, and all manner of wild, incendiary talk was indulged in, but

the rioters were ultimately convinced of the utter folly and uselessness of

their course and quiet was restored... The dead foreigners were buried with much

pomp and ceremony, five thousand sympathizers following their coffins to their

graves.

|

Frank Leslie's Illustrated, 1891 |

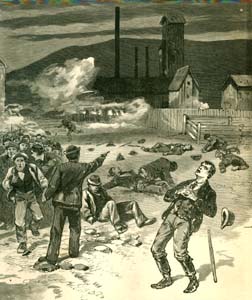

An artist's sketch of the exchange of gunfire at Morewood is seen here.

The violence at Morewood was just a prelude to the following year's much-better known "Homestead Strike of 1892" where 35 men were killed and at least 400 injured in the "bloodiest and most crucial labor conflict in American history," wrote Leon Wolff in his 1965 book, Lockout. It involved a battle in Pittsburgh between 13,000 workers affiliated with the fledgling Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, and Pinkerton National Detective Agency security teams hired by Carnegie Steel to protect the massive Homestead works. Wrote Wolff: "The mill owners were led by Henry Clay Frick, the iron-willed coke king. Although the surface issue was wages, the basic issue was Frick's determination to break the union and run the mill as an open shop."

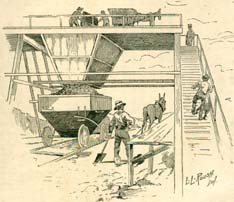

One of the coal loading facilities in the Mount Pleasant region, at which Lewis no doubt would have worked, is seen here.

|

Mount Pleasant coal works |

How Lewis and Marietta were involved or coped with the anxiety of such a violent community environment is not known, but can only be imagined. There is no question, though, that they would have had to have been very strong to live with that natural fear always in the back of their minds.

~ Marietta's Declining Health ~

As her family got larger almost every year, Marietta was sickly and often unable to provide proper care. Her eldest daughter Lucinda carried much of the responsibility for raising the children.

In May 1912, the Crosbys moved to a new home in Stauffer, near Mt. Pleasant. Eldest daughter Lucinda, in a penny postcard to her cousin Lula (Stairs) Swift, wrote: "

Mama is sick to day. Her heart is so bad. Lulu you will have to excuse this dirty card. I am run out of cards. Will you and Bessie send James a card Sat June 10. He will be 14 year old.

On Feb. 1, 1911, Lucinda wrote: "Mama isn't any better." On March 7, 1912, Lucinda wrote: "Mama is better and so are the kids and I am glad of it. I am washing today and I haven't a very nice day for it."

Sometime in the early 1900s, Lewis and Marietta attended a Crosby reunion at Iron Bridge, near Mt. Pleasant along with Marietta's sister Mattie Stairs in the center. A photograph of the three sitting together shows that Marietta had streaks of premature grey in her hair.

|

|

|

Crosby Reunion at Iron Bridge near Mt. Pleasant, PA |

|

L-R: Lewis, Mattie Stairs, Marietta |

Marietta knew how to sew, and used her talent to make inexpensive but thoughtful gifts for the family. Just after Christmas 1911, she made a doll's hood for the young daughter of her niece Lula Swift. It was to be Marietta's last Christmas.

As Marietta's eldest daughter, Lucinda bore a heavy responsibility in managing household duties and watching the younger children. Writing in June 1911, Lucinda confided to her cousin Lula that "Mama is sick to day. Her heart is so bad." On March 7, 1912, Lucinda wrote: "Mama is better and so are the kids and I am glad of it." Then on May 6, 1912, after the family apparently relocated to a new house in Buckeye, Lucinda wrote again to Lula, saying "We got moved last Wednesday but we have got lots of work to do. We have such a dirty house and every room has to be papered and painted and I am tired."

For her final six months in 1912, Marietta lay deathly ill in her home, suffering from tuberculosis and abscess of the lungs, coughing violently. Her son recalled that "They said you could hear her out on the road." She succumbed to her illness at the age of 43 on Aug. 8, 1912. She was laid to rest at Greenlick Cemetery near Bridgeport.

|

Greenlick Cemetery |

~ Lewis's Final Years ~

Lewis may have married again, to Lucinda (?), as evidenced by the 1920 census listing of Westmoreland County.

After a fall at the Morewood Mines, Lewis retired from his work as a master mechanic in March 1931, having completed 46 years of service. A newspaper article noted that at the time of retirement, he had been "in very poor health for the past five months."

Suffering from cancer of the stomach, Lewis only lived for six more months. He is known to have undergone a laparotomy, an incision in the cancerous area so physicians could examine the extent. He died just three days shy of his 64th birthday on Sept. 6, 1931. In an obituary, the Connellsville Courier said he had been ill ever since he had received his pension. Daughter Lucinda was the informant for the official Pennsylvania certificate of death.

Marietta and Lewis sleep side by side for all time at Greenlick Cemetery.

|

Copyright © 2000-2001, 2005, 2010, 2017, 2020 Mark A. Miner |

|

Sketches of the Morewood Mine shooting (by M. De Lipman) and coal loader (by L. L Roush) originally published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, April 18, 1891. |