|

Edward Harlan McReynolds |

|

E.H. McReynolds |

Edward Harlan "E.H." McReynolds (1890-1937) was born on Oct. 18, 1888 near Butler, Bates County, MO, the son of George E. and Anna (Swearingen) McReynolds.

He was an early Missouri newspaperman who while in the Army convinced heavyweight boxer Gene Tunney that he could beat champion Jack Dempsey. Later, he rose to become a prominent railroad official in St. Louis in the 1920s and '30s, and was chairman of a prestigious national advertising association, before a financial scandal wrecked his career and led to his tragic demise.

Edward's first few years were spent in Butler and then in the mid-1890s for two years at Sprague, MO. Then in 1896, he and the family made a move to Rich Hill which became their permanent home.

He showed an early interest in reading, books and theatre. In October 1907, at the age of 19, he was elected vice president of the Athenian Literary Society, which was organized at the Bryant School. Said the Rich Hill Tribune, "This society enjoys an enviable reputation and starts out this year with a good membership." In May 1908, at age 20, he graduated from Rich Hill High School with exercises held at the school building, which "was beautifully decorated with school colors and pennants," reported the Tribune. Edward performed in a comedy that day, along with Marie Stebbins, Howell Heck and Naomi Davis.

|

|

|

Edward in 1928 in Mexico and as a boy of age three, as published in the Mo-Pac magazine |

Upon graduation, Edward was hired on the Tribune staff. He nearly had a finger amputated in a freak accident in January 1909, as reported by his employer: "Ed McReynolds, one of the Tribune force, caught his thumb in a press Saturday and had a narrow escape of losing that member, the machine just missing the middle joint. The injury was not serious."

He served with the U.S. Marines during World War I, and was stationed overseas in 1918 when his mother died. He apparently was unable to get home for her funeral.

~ A Momentous Meeting with Boxer Gene Tunney ~

Early in his career, Edward was a reporter for his hometown newspaper, the Bates County Democrat, and then moved on to reporting assignments in Joplin, St. Joseph and Jefferson City, MO. In covering sports, he had an opportunity to attend boxing matches where he got to see heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey in action.

|

|

| Gene Tunney, above left, as world heavyweight champion, and as a doughboy in the Army during World War I (Pathe Photo). |

When Edward went to France in the Army, said the St. Louis Globe Democrat, Edward "managed the boxing tournament in which Gene Tunney got his start as a pugilist. Tunney later credited McReynolds with giving him the idea he could defeat Jack Dempsey."

Apparently the two met when Tunney, a member of the United States Marine Corps, fought in exhibition matches in Germany to entertain the troops, wearing his mantle as light heavyweight champion of the American Expedition Force (AEF). Calling Edward "a brainy peacetime sports writer," Tunney asked for an opinion. Edward countered by saying Dempsey was a bruising puncher and could be beaten by someone "fast, shifty, hard-hitting, a killer." Tunney made up his mind that he could beat Dempsey using a similar approach, and gave Edward credit for the idea.

|

|

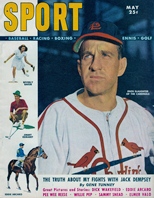

| Published accounts of Edward's conversations with Tunney in Sport Magazine and Reader's Digest, and below, Twentieth Century Treasury of Sports, When Dempsey Fought Tunney and At the Fights: American Writers on Boxing. |

|

|

The story originally mentioning Edward was told on the pages of Sport Magazine (May 1949), reprinted later that year in Reader's Digest (August 1949) as part of the advance publicity for the book The Aspirin Age: 1919-1941: The Essential Events of American Life in the Chaotic Years Between the Two World Wars by Isabel Leighton (Simon & Schuster, 1949). It was republished in At the Fights: American Writers on Boxing, edited by George Kimball and John Schulian (Library of America, 2011).

Later, it was excerpted in such books as The Twentieth Century Treasury of Sports (Viking Penguin, 1992) by Al Silverman and Brian Silverman); Tunney: Boxing's Brainiest Champ and His Upset of the Great Jack Dempsey by Jack Cavanaugh (Ballantine Books); When Dempsey Fought Tunney: Heroes, Hokum, and Storytelling in the Jazz Age, by Bruce J. Evensen (University of Tennessee Press, 1996); and Jack Dempsey: The Manssa Mauler by Randy Roberts (Louisiana State University, 1979). The irony is that in When Dempsey Fought Tunney, Edward's name was incorrectly stated as "Edwin;" in Tunney: Boxing's Brainiest Champ, his name errantly was printed as "Jack;" and in Jack Dempsey, the Manassa Mauler, he was called "James."

~ Marriage to Augusta B. Clay ~

At the age of 21, Edward married 18-year-old Augusta B. Clay (1891-1970) of Butler. The marriage license was filed in September 1909, in Kansas City, Jackson County, and presumably they were wed shortly thereafter. They had no children.

The McReynoldses lived at many places, but the first known one was the year after marriage, when they made their home in El Dorado, Butler County, KS, as shown on the 1910 census. That year, Edward worked as a printer at the Times office, and they boarded with the family of Cal and May Fish on Mechanic Avenue. Later dwelling places in St. Louis were at 5540 Delaware Boulevard and an apartment at 418 Clara Avenue in St. Louis, MO.

During World War I, Edward and Augusta lived in Joplin, MO, where he worked as a telegraph editor for the Joplin Globe newspaper. Their home was at 919 Jackson Avenue. When registering for the military draft, in June 1917, he was described as tall and of medium build, with light brown eyes and dark brown hair.

As a journalist, Edward undoubtedly covered the business of the railroads which were such a significant part of the Kansas City and Northwest Missouri economy at the time. Among these would have been the Missouri Pacific Railroad ("Mo-Pac"), and his abilities as a writer must have caught the attention of top railroad officials, such as Missouri Pacific president Lewis W. Baldwin. The Mo-Pac was based in St. Louis with a major operation in Houston, TX.

|

|

MOPAC President L.W. Baldwin |

~ Joining the Mighty Missouri Pacific ~

|

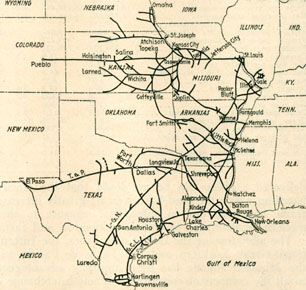

In 1923, at the age of 35, Edward was hired by Baldwin to fill a public relations position with the Missouri Pacific, based in St. Louis. Over the sweep of 13 years, he rose to become assistant to the president and director of publicity-advertising for the railroad as it executed a broad expansion strategy. Said the Globe-Democrat, "He was widely known as a spokesman for the company."

Baldwin hired Edward at a time when the Mo-Pac was making significant expansions into Texas and Louisiana with the acquisition of the Gulf Coast Lines, International Great Northern and San Antonio, Uvalde & Gulf Railroad. Edward later wrote that they worked to unite the company culture in a "spirit of wonderful cooperation that helped President Baldwin to accomplish the almost miraculous achievements of those years from 1923 to 1930 when the Missouri Pacific Lines was brought from far back in the list of great railroads to away out in front."

How Baldwin and Edward met is unknown, but possibly could have been a result of a newspaper interview Edward needed for a story.

|

|

|

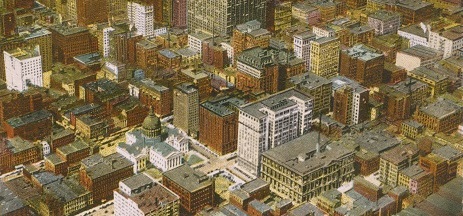

Bird's-eye view of downtown St. Louis of Edward's era |

|

MOPAC headquarters |

Edward and Augusta thus moved across state to St. Louis to begin their new phase of life. Edward was given the title "Assistant to the President," and he began to build what likely have been the Mo-Pac's first specific public affairs position.

He thus undertook what appears by any measure to have been an aggressive and high profile body of work over the next 15 or more years, working in close coordination with his boss, whom he admired highly.

Edward hit the ground running in his new role, operating from the Missouri Pacific's 22-story corporate headquarters building in downtown St. Louis. He was named in a January 1925 article in The Frisco Employes' Magazine as a member of the Conference of Railway Editors, serving on a committee to prepare a new constitution and by-laws. Other members of the committee were Floyd L. Bell of the Frisco (St. Louis-San Francisco Railway) magazine, Hugh L. Moore of the M.K.T. Magazine and Ray D. Casey of the Pennsylvania News.

Another article in the same issue of the Frisco Magazine praised how Edward and his field editor Ike Brown filled the Mo-Pac magazine with "interesting stories of men and women along the lines. The field notes of this magazine have proven unusually entertaining and profitable to its readers."

During his 14 years with the company, Edward made thousands of personal friends among employees in virtually every division and department. Especially among them, he noted, were the officers of the traffic and operating departments who "always eagerly responded" to his every call and suggestion.

|

|

|

~ Highlights of Edward's Missouri Pacific Lines Career ~ |

|

|

Early Missouri Pacific locomotive and coal car |

| 1923 | June - Joined the company. The Washington (MO) Citizen reported on June 29 that he was "an experienced publisher and editor [and] has been employed to manage the magazine. An organization of division editors and correspondents with representatives at all division point and other important centers on the road is to be built up at once. The magazine is the outgrowth of plans entertained by Mr. Baldwin and other general officers of the Missouri Pacific. Through it, employes will be made better acquainted with each other and with the system and their mutual necessities." |

| July - The first edition of The Missouri Pacific Magazine was printed, priced at $1.00 per year or 10 cents per copy. | |

| 1926 |

July

4-11 - Served on executive committee and as toast master for the Mo-Pac's

75th anniversary, a sweeping "Pageant of Progress" theatrical

performance telling the story of Western explorers and railroad pioneers,

involving hundreds of employee musicians, singers, actors and historical

re-enactors, held at Washington University Stadium in St. Louis. The

booklet contains the extensive agenda and names of

hundreds of employees. July

4-11 - Served on executive committee and as toast master for the Mo-Pac's

75th anniversary, a sweeping "Pageant of Progress" theatrical

performance telling the story of Western explorers and railroad pioneers,

involving hundreds of employee musicians, singers, actors and historical

re-enactors, held at Washington University Stadium in St. Louis. The

booklet contains the extensive agenda and names of

hundreds of employees. |

|

|

|

Employees and officers in pageant costumes for the Mo-Pac's 75th anniversary (Railway Age, July 17, 1926) |

| 1926 |

Gave a speech on "What Motion Pictures Have Done for Railroads" - referenced in The Educational Screen, Vol. 5. |

| 1927 |

March - Hosted the Third International

Tour of the American Agricultural Editors Association, traveling from St. Louis

to Mexico City, where they met with President of Mexico Plutarco Elias Calles.

The tour was summarized by George Mertz Slocum in his 1927 book, Where Tex Meets

Mex: A Report of Recent

Ramblings on Both Sides of the Rio Grande. Mertz said the railroad "has

fostered a system of agricultural development which is probably unmatched

anywhere else in America. Competent agricultural advisors under pay of this

railroad, are located at all strategic points along its route and give their

full time and energy to helping the farmer and planter succeed in his attempt to

'get away from cotton'." March - Hosted the Third International

Tour of the American Agricultural Editors Association, traveling from St. Louis

to Mexico City, where they met with President of Mexico Plutarco Elias Calles.

The tour was summarized by George Mertz Slocum in his 1927 book, Where Tex Meets

Mex: A Report of Recent

Ramblings on Both Sides of the Rio Grande. Mertz said the railroad "has

fostered a system of agricultural development which is probably unmatched

anywhere else in America. Competent agricultural advisors under pay of this

railroad, are located at all strategic points along its route and give their

full time and energy to helping the farmer and planter succeed in his attempt to

'get away from cotton'." |

|

|

| Edward (blue dot) and members of the American Agricultural Editors Association meet President of Mexico Calles (red dot) during their 1927 tour |

| 1928 |

May

- Helped lead a 50-person delegation from the American Agricultural Editors

Association, including wives and children, on a three-week, 8,000 mile journey

over company rail lines and connections "to gain knowledge of farm

conditions and farm problems." The journals represented on the trip

"literally blanket the farm populations of the Middle West and South,"

with a combined circulation of nearly 50 million readers. The journalists voted

it their "best ever" trip. May

- Helped lead a 50-person delegation from the American Agricultural Editors

Association, including wives and children, on a three-week, 8,000 mile journey

over company rail lines and connections "to gain knowledge of farm

conditions and farm problems." The journals represented on the trip

"literally blanket the farm populations of the Middle West and South,"

with a combined circulation of nearly 50 million readers. The journalists voted

it their "best ever" trip. |

| 1928 | Made a "tremendously interesting" speech on how the Mo-Pac used publicity to "sell" the railroad to employees and making each one an ambassador, published in the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company's Industrial Bulletin, 1928. |

| 1928 | Welcomed joint convention to St. Louis of the Railway Car Department Officers' Association and Southeast Master Car Builders' and Supervisors' Association, saying "there is too great a tendency for railroad men to confine their efforts and attention solely to their respective departments, losing sight of the fact that only through close co-operation can the best results be secured." Published in Railway Locomotives and Cars, Vol. 102, 1928. |

| 1929 | Addressed a convention of the Passenger, Ticket and Freight Agents Association, about the dawn of opportunity that Texas held for railroad business. Published in the Stone & Webster Journal, Vol. 44, 1929. |

| 1929 | Directly involved with the railroad's purchase of a specially built three-place Travel Air biplane for business use, noted in Aeronautical Industry, 1929. |

| 1929 | Spoke on "The St. Louis Gateway and Its Relation to Transportation of the future" at a convention, reported in the Official Proceedings of the St. Louis Railway Club, Vols. 34-35, 1929. |

| 1930 | Promoted to Director of Publicity-Advertising for all departments of the Mo-Pac, as reported in Printer's Ink, Vol. 151, 1930. |

| 1931 |

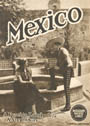

Aug. 10-14 - Served as director of

transportation for the regional meeting in Mexico City of the Press Congress of

the World. Other leaders of the event included field secretary Omar D. Gray of

the Sturgeon (MO) Leader and convention chairman Frank L. Martin,

associate dean of the School of Journalism at the University of Missouri. The New

York Times ran a short advance article on March 13. Seen here, a

Mo-Pac booklet touting Mexico as a tourism destination. Aug. 10-14 - Served as director of

transportation for the regional meeting in Mexico City of the Press Congress of

the World. Other leaders of the event included field secretary Omar D. Gray of

the Sturgeon (MO) Leader and convention chairman Frank L. Martin,

associate dean of the School of Journalism at the University of Missouri. The New

York Times ran a short advance article on March 13. Seen here, a

Mo-Pac booklet touting Mexico as a tourism destination. |

| 1932 | Gave address on "The Transportation Situation" at the annual convention of the Southeast Missouri Retail Lumber Dealers Association at the Hotel Marquette in Cape Girardeau, MO. |

| 1933 | Served on the "Location and Design of Airports in Co-ordination with Railway Facilities" subcommittee of the American Railway Engineering Association, reported in the association's Proceedings, Vol. 34, 1933. |

| 1933 | Gave address, "A New Deal for Transportation," to the Traffic Club of Kansas City and the Trans-Missouri-Kansas Shippers Board. The speech later was reprinted in a 28-page booklet. |

| 1935 | Testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Interstate Commerce on how the Transportation Association of America "can be of assistance in combating government ownership of railroads..." as reported in Investigation of Railroads, Holding Companies, Affiliated Companies, Part 23, 1937. |

| 1935 | As a member of the Western Association of Railroads, helped organize Railroad Week which "helped put Western Railroads definitely on the map and into the minds of the public," reported The Milwaukee Magazine of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad. |

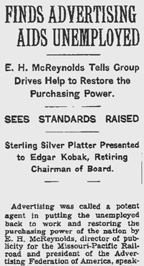

| 1936 | July 1 - Elected president of the Advertising Federation of America (today the American Advertising Federation), for a one-year term, noted in the New York Times and Nation's Business magazine (Vol. 24, 1936). |

| 1936 | Oct. 29 - Gave an address to the Chicago Federated Advertising Clubs, covered by the New York Times, urging "continued self-regulation of advertising" rather than government intervention, and citing how the Better Business Bureau as well as newspapers and other media "have done a magnificent job of self-censorship. It is almost impossible to find a questionable advertisement and nostrums, quacks and fakes are fought consistently." |

| 1936 | Dec. 10 - Spoke on "Advertising at the Crossroads" at the Advertising Club of New York, broadcast on WOR-AM Radio and covered by the New York Times. |

| 1937 | Served as national president of Alpha Delta Sigma, an honor society recognizing and encouraging scholastic achievement in advertising scholastics, sponsored by the American Advertising Federation. |

| 1937 | Presented a "vocafilm" to the Association of American Railroads entitled All Aboard, referenced in the association's Proceedings, Vol. 17, 1937. |

| 1937 | June 21 - Spoke at the Advertising Federation of America annual convention in New York City, making remarks on "reselling the American ideals back to the people," reported the New York Times in a story that carried his photograph. He called on the AFA to make "a serious study and an attempt to find the answer of the problem of a wider education of every man, woman and child in America with regard to the inter-related interests of producers and consumers, capital and labor, the entire public and governmental agencies -- and between each and all of these with each other -- and the part advertising has played ... kin this vast and complicated economic problem." |

|

Cornelius Vanderbilt IV |

~ Friendship with Cornelius "Neil" Vanderbilt IV ~

In the late 1920s or early '30s, Edward was introduced to a prominent new friend and wealthy railroad heir Cornelius "Neil" Vanderbilt IV. The son of Cornelius and Grace (Wilson) Vanderbilt, III he came from a branch of the ultra-wealthy family that was known for publicity-seeking. As the namesake and great-grandson of a shipping and railroad magnate, Neil had been a newspaper reporter with the New York Herald and later the New York Times before going to work for publisher William Randolph Hearst and writing by-lined articles under the name "Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr." He went on to found ill-fated newspapers such as the Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News, San Francisco Illustrated Daily Herald and Miami Tab.

|

Edward's letter to Vanderbilt |

Thus, with common interests in railroads and journalism, Neil's friendship would have been of natural appeal to Edward. Neil was married at that time to the second of his seven wives, Mary Weir Logan, whom he had wed in 1928.

As evidence of their friendship, Edward wrote Neil a letter on Missouri Pacific letterhead dated June 5, 1931, seen here, with the original preserved today in the Minerd.com Archives. It was addressed to Neil at a hotel in Reno, NV, and was a reply to an earlier letter from Neil. Edward's letter stated in full:

Dear

Neil:

Hope the legal complications mentioned in your letter

are not of serious consequence and that your stay in Reno will not last too

long.

For the next few weeks most of my time will need to be

spent in Texas and the Southwest. I expect to get west sometime in July and if

you should still be out that way I will try to locate you somewhere. In the

meantime, if you should come east, it is possible your itinerary will bring you

by way of St. Louis. I hope so.

By the way, the information I have is to the effect

that it won't be long until the Mexican Government probably can set a date for

the official opening of the highway to Mexico City, at which time I suppose you

will want to revive your plan of offering a trophy for an automobile road race

under certain conditions and restrictions. If we can be of any help in

connection with that matter at any time, please feel free to call on us.

Hope Mrs. Vanderbilt's health has greatly improved.

Mrs. McReynolds joins me in the best of wishes.

~ Editorship of the Missouri Pacific Lines Magazine ~

|

|

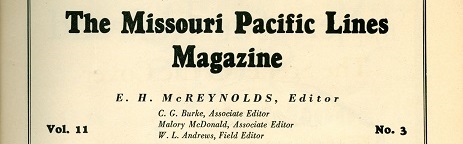

| Edward's name on the title page of the Mo-Pac magazine, 1934 |

|

| May 1934 |

Among Edward's responsibilities was producing the monthly Missouri Pacific Lines Magazine over the span of 14-plus years. Of that time, he later wrote of his gratification in the "continuous publication of what has come to be widely acclaimed as one of the outstanding employe magazines in America."

The May 1934 and the February-March 1937 editions are here. Click to see a summary of all the original editions preserved today in the Minerd.com Archives.

|

|

Feb-March 1937 |

The May 1934 issue was an extensive undertaking containing 84 pages, including wraps. The cover painting shows the "world famous Royal Gorge of the Colorado Rockies, through which the Scenic Limited winds its way between St. Louis and the Pacific Coast."

While Edward's name always was prominently printed on the magazine's title page masthead, he was careful not to insert himself into the magazine's editorial coverage. In fact, in his farewell message printed in the June-July 1937 edition, he said "we have definitely tried for fourteen years to keep our own personalities out of the column of the Magazine."

Articles submitted by employees all across the country highlighted the Mo-Pac's booster clubs, safety, agriculture, new technology, sports, retirements. These ranged from the Texas-Louisiana Lines, Mechanical Department and Transportation Company to Mexican operations and Colored Employees, including full-page articles in Spanish. Edward was assisted in this work by associate editors C.G. Burke and Malory McDonald and field editor W.L. Andrews.

Yet in the July 1928

edition, Edward's colleagues on the editing staff were involved in

"slipping one over" on him by publishing photographs of him -- without

his knowledge or consent -- as an adult and as a boy of age three in Butler,

wearing a fez. The headline read: "I Knew Him When---," and the

surprise was completed "with the help of Mrs. McReynolds," according

to the caption.

|

|

|

Collage of Mopac Lines Magazine covers, 1920s and 1930s |

~ Great Depression Slows Rail Transportation Business ~

During the seven year period between 1923 and 1930, Edward played a vital role in the Missouri Pacific's corporate communications at a time of continuous improvement. He later wrote that "It has been that spirit of friendliness and mutual help -- co-operation -- that has enabled the Missouri Pacific Lines to ... meet destructive competition; improve the physical properties of the system; improve the service, both freight and passenger; air condition the passenger train equipment; reduce rates and fares; and face the future with confidence and courage."

|

|

Mo-Pac's "Sunshine Special" |

Seen at right: the Mo-Pac's air-conditioned "Sunshine Special," billed as "It's 70° in 'The Sunshine' When It's 100° in the Shade" and covering the territory between St. Louis-Memphis and Louisiana, Texas, Mexico, Arizona and California.

But in 1933, with the nation in the grip of the Great Depression, the Mo-Pac's business declined to the point of insolvency. Edward wrote that the company had to "weather a depression such as never before was recorded." He gave a speech that year, "A New Deal for Transportation," delivered to the Traffic Club of Kansas City and the Trans-Missouri-Kansas Shippers Board. The speech was reprinted in a 28-page booklet. (A copy is held today in the John W. Barriger III Papers in the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library, a special collection of the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri St. Louis.)

The bankrupt company was reorganized in 1933 under the control of a federal court-appointed trustee, with President Baldwin continuing as chief executive. Edward and the executive team took significant pay cuts during the restructuring period. Fighting to keep the company solvent, Edward used press articles to emphasize the benefits that the Missouri Pacific provided to customers as well as its central role in the economy. As one example, a Dec. 1, 1934 feature article in Railway Age stated that the Mo-Pac was still:

-

the same great "service Institution" that they have been throughout their history...

-

performing an essential transportation task in the nine Southwestern states which they serve...

-

strategically located to function most efficiently for their patrons...

-

made up of well-maintained tracks, modern equipment and adequate auxiliary facilities...

-

In a word, the Missouri Pacific Lines still are, despite everything, the kind of railroads they long have been -- well-equipped, ably managed and ready to serve their patrons with transportation of the highest standards for themselves and their shipments.

|

|

|

Map of the Mo-Pac's rail routes, circa 1928 |

|

N.Y. Times, Dec. 10, 1936 |

With business continuing to linger in the doldrums midway through the 1930s, Edward took on more of a national persona, perhaps to meet prospective employers who could pay a higher salary. He served in 1934 as president of the Advertising Club of St. Louis, and in 1936 was elected president of the American Advertising Federation (AAF). In this role, he received extensive positive publicity, including many articles from the New York Times. Of course the Times had a natural vested interest in promoting the value and quality of advertising as a mechanism for helping turn around the nation's floundering economy.

He also served in 1937 as national president of Alpha Delta Sigma, an honor society recognizing and encouraging scholastic achievement in advertising scholastics, sponsored by the AAF.

In a speech to the Advertising Club of New York on Dec. 10, 1936, which was reported at length by the Times, Edward said that advertising was a "potent agent in putting the unemployed back to work and restoring the purchasing power of the nation." He was quoted directly in saying, "Just as advertising made possible the almost unbelievable widespread distribution of the products of business and industry in the past and enabled the automotive industry to whip the depression ahead of all others, so it will light the way out of our present difficulties."

~ Income Tax Problems and a Tragic Downfall ~

Edward's lofty position began to unravel in mid-1937 when it was alleged that he had failed to pay state income taxes. He resigned from the Mo-Pac on June 30, 1937, with the unfortunate news covered by the New York Times, among other publications. The reason for the change, said the Times, was to accept a new position as vice president of sales for the James Mulligan Printing and Publishing Company in St. Louis.

As Edward prepared to leave the railroad's employ, he penned a full-page farewell column, printed in the June-July 1937 edition of the magazine. He announced that John F. Rector would rejoin the company and take his place, "one of the most popular and able men ever employed in the Magazine, Publicity and Advertising department." Rector previously had served the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad under president and board chairman M.S. Sloan.

|

Edward's farewell

column, mid-1937 |

In his goodbye, Edward wrote the following with a good deal of foreshadowing:

The railroad -- the Missouri Pacific-- and the Western and American railroads -- have been exceedingly good to me. They have afforded countless opportunities to do interesting and worth-while things. And, as a result of those opportunities, they have resulted in many honors coming my way. For all of which I will be eternally grateful. Always I will remember the opportunity and the privilege of working with the Missouri Pacific Boosters. That work, with one single exception, has been the happiest in my life. The splendid, inspiring men and women who make up this Missouri Pacific constitute, I know, the greatest organization in America. The single exception mentioned has been the privilege of knowing and working for the greatest railroad executive in the world -- and one of the greatest citizens. So long as I live, the Missouri Pacific will be "my" railroad. There never will come a time when it will not rank first in my affections... It is with a heavy heart and longing eyes cast backward that I go to what I hope will prove greater opportunities for me personally-- but which never can be happier -- and way, in parting: "Adios--hasta la vista."

When the Mulligan Printing arrangement did not work out, in early December 1937 Edward then joined the staff of the Republican State Committee to handle publicity. The following week, reported the Globe-Democrat, "he was among a group of St. Louisians sued by the Attorney General's office for delinquent state taxes. The state was seeking to collect from him $597.75 for the years 1930, 1931 and 1932, based on three years taxable income of $16,990."

In a state of deep depression, Edward allowed himself to be disturbingly moved by a quote from the comedy film Nothing Sacred which was then playing at local theatres, starring Carole Lombard and Fredric March:

I'll tell you briefly what I think of newspapermen. The hand of God reaching into the mire could not raise them to the depths of degradation. Up and down and back again.

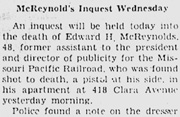

|

Missouri news story, 1937 |

Four days before Christmas 1937, Edward decided to end his life. While Augusta and her sister Mattie C. Daniels were having breakfast one morning in the kitchen of their home, Edward went into the bedroom and shot himself in the head. A note he left at the scene quoted the Nothing Sacred line. Distraught, Augusta called police, and Sergeant Wallace Schucart arrived to investigate.

Following a funeral service held at Alexander Chapel, Edward's remains were cremated at the Valhalla Cemetery. The final resting place for his ashes are not yet known.

The news was distributed nationwide by the Associated Press, making headlines in the New York Times as well as in St. Louis and Edward's hometown of Butler. His death also was covered in important national journals such as Business Week and Industry Week. A coroner's inquest was held but the results are not yet known.

~ Augusta's Decades as a Widow ~

|

|

Toward Professionalism

|

Augusta never re-married and remained Edward's widow for another 33 years.

She kept her home in St. Louis, where she was Matron of Tucan Chapter 68 of the Order of the Eastern Star, member of the Temple Club Scottish Rite Women's Club and President of the St. Louis Chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR).

At the age of 79, three days before Christmas 1970, Augusta died in St. Louis. Funeral services were held at the Alexander & Sons Crestwood Chapel. A brief obituary appearing in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted that she was the "wife of the late Edward H. McReynolds, sister of Martha C. Daniels, aunt of Naydeen C.D. Urquhart."

~ Edward's Legacy ~

Despite its many troubles, the Missouri Pacific remained in business for several decades after Edward's death. In 1980, suffering from the decline of passenger railroads, it was acquired by the Union Pacific Railroad, and its name and brand disappeared.

Edward's legacy in American popular culture has largely faded. But at rare times, he has received public credit for his accomplishments.

In 1969, he was pictured and named on several pages in a book published by Alpha Delta Sigma, Toward Professionalism in Advertising: The Story of Alpha Delta Sigma's Aid to Professionalize Advertising Through Advertising Education, 1913-1969. The book is authored by Donald G. Hileman of Southern Illinois University and Billy I. Ross of Texas Tech. A copy today is preserved in the Minerd.com Archives.

|

Copyright © 2000, 2002, 2008-2013, 2018, 2024 Mark A. Miner |

|

E.H. McReynolds portrait at the top of this biography courtesy of the American Advertising Federation |