|

Catherine

(Miner) Hanshaw |

|

Union Cemetery, Newburg |

Catherine (Miner) Hanshaw was born on Sept. 10, 1814, near Kingwood, Preston County, WV, the daughter of Burket and Frances (Skinner) Minerd. She and her husband were popular hotel keepers of Preston County. Tragically, and he and two of their sons are thought to have been killed in railroad accidents.

Catherine's grave marker, seen here, was nearly illegible when photographed in August 1997.

Catherine was united in the bonds of holy matrimony Hiram B. Hanshaw (1810-1870), who had migrated to Kingwood in about 1830, according to a local history.

We are researching whether Hiram might have been from Bunker Hill, Berkeley County, WV, and possibly the son of either Levi or Hiram Hanshaw, who both were military officers during the War of 1812. Hiram may be the same "Hiram Henshaw" enumerated in the federal census of 1840 in Berkeley County, WV, living in the vicinity of James Henshaw and Joseph Henshaw, but his exact origins are not known. He was referred to as "Captain," but any military service he may have rendered has not been verified.

The Hanshaws together produced a brood of 15 children -- Sarah F. Overfield, James E. Hanshaw, Ruhama Menefee, Dr. Guy R.C.A. Hanshaw, Jane "Jennie" Huggins, George Walters Henshaw, William H. Hanshaw, Matilda E. Purinton, Margaret E. Hanshaw, Agnes Hoge, Charles F.W. Hanshaw, Robert Moses Hanshaw, Julia M. Fawcett, Helen M. Hanshaw and Apalona Hanshaw.

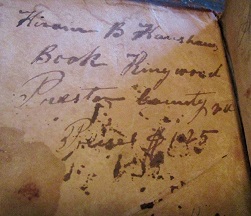

He is believed to have been a relative of George W. Hanshaw whose father-in-law, Jesse Hughes, was a widely known Indian scout in what today is the Clarksburg area of West Virginia. In fact, Hiram purchased and signed a copy of a book about Hughes and the era, entitled Chronicles of Border Warfare, or History of the Settlement By the Whites, of North-western Virginia and of the Indian Wars and Massacres in that Section of the State. The volume was published in Clarksburg in 1831 by Joseph Israel.

|

Hiram's inscribed copy of Chronicles of Border Warfare, 1831 |

|

Booklet naming the Hanshaws |

In 1842, Catherine and her married sister Rebecca Murdock were members of the Kingwood Methodist Church at the time the congregation erected a new, brick building. In a 1950 history of the church, seen here, and entitled Through the Years: A History of Methodism in Kingwood, West Virginia, author Ethel Peaslee Beerbower writes the following:

For several years the young and rising church felt the growing need of a house of worship which they might call their own, and eventually became convinced that they would enjoy a larger measure of divine blessing if they would erect a house for the Lord. In 1841, the bricks were made and in the fall of 1842 the present (1874) church was dedicated by Reverend William Hunter, then Presiding Elder of the District, at a Quarterly Meeting held by him," says a history of the church. "At that time the church was not yet plastered and the seats had not yet been made. The congregation was seated on planks supported by blocks of wood. The pulpit, an elevated box in the style of the day, was the only part of the interior which was completed. As soon as possible, in 1844, the church was plastered and the seats were completed in 1849.

The names of Catherine and Rebecca, among 43 members of the church at the time of the brick building project, were part of a list compiled some years later by Persis Hagans McGrew, who "had to rely entirely upon her memory." In this list, Catherine's last name is spelled "Handshaw." A copy of this very rare booklet today is preserved in the Minerd-Minard-Miner-Minor Archives.

|

|

View at the top of Cheat Mountain, two miles west of Aurora, along what is now Route 50. Elevation above sea level: 2,750 feet. |

|

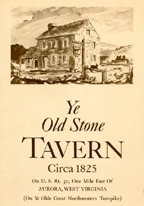

Booklet naming Hiram |

Hiram was an early tavern and hotel keeper throughout his lifetime. The first known record of his work was at the "Old Stone Tavern" near Aurora, Preston County, WV, just a few miles from the Maryland border. The tavern had been built in 1825 but was not operated as a tavern until 1841. He followed George G. Houser, and was succeeded by William H. Grimes, sometime after 1841. Hiram and the tavern are mentioned in a booklet, Aurora Community, published in 1950 by the Aurora Community of Preston County. Referring to the tavern, said the book, "Later it became the residence of Christian Selders and is now the home of Clinton Wotring, whose wife is a granddaughter of Mr. Selders," According to a state of West Virginia historical marker erected at the site, it was the first tavern in the Union District on the Northwestern Turnpike (today's Route 50). The marker was erected in 1987 by the West Virginia Department of Culture and History. Today the site is at the northern tip of the 919,000-acre Monongahela National Forest.

The federal census of 1850 shows the family residing in Barbour County, WV. Catherine is shown as head of the household, at age 36, and Hiram's whereabouts are not shown. Son James, age 18, is listed as a farmer. At some point the family moved again, to nearby Preston County.

By 1855, Hiram had been appointed by the federal government as postmaster for the town of Evansville, Preston County. This fact and his name are recorded in the 1855 government publication, List of Post Offices in the United States, compiled by D.D.T. Leech.

The Hanshaws moved to Evansville, and later went on to reside in the small towns of Independence and Newburg, Preston County. Hiram gave up the post office work, and became well known for running "ordinaries," or eating establishments, as well as hotels, including the "Gordon House" at Evansville and the "Hanshaw House" at Independence.

|

|

Old Stone Tavern and West Virginia historical marker, photographed in 2009. See enlarged version, our Oct. 2009 "Photo of the Month." |

|

Son William's grave, 1855 |

Heartache rocked the family in 1855. That year, on April 12, their 15-year-old son William died of typhoid fever. He was laid to rest in the cemetery of the United Methodist Church in Evansville. Seen here, William's grave marker still stands, and is fairly legible, photographed during a visit in August 2004. The fate of daughter Apalona Hanshaw (1848- ? ) is unknown.

A year later, on Oct. 18, 1856, one-year-old daughter Margaret died of tuberculosis, or "consumption" as it was then known. Her burial site is unknown.

According to the 1979 book, Preston County West Virginia History:

In the 1800s Evansville was a flourishing town. Its growth was due to the building of the Northwestern Turnpike (now U.S. 50). Its growth stopped with the coming of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

At Independence, the Hanshaws owned two houses, one of which was their residence, and the other a hotel. The hotel was painted yellow, presumably to attract attention in the bustling railroad town. The two structures were located near the juncture of what is now Route 33, Route 31 and Hollow Road; the CSX and Baltimore & Ohio Railroad tracks; and Cooks Run (the north fork of Raccoon Creek). One of the buildings stands today, as a private residence, though part of it was removed at one point in time. The structure later was sold to George Weaver.

|

Rare photo of Independence promoting the 16th annual "Melon Sales Day" in 1908. Click to enlarge. |

During the Civil War, as with many families of that era, the Hanshaws must have agonized when son Guy and son in law Eugene Huggins and Thomas Purinton joined the Union Army. In fact, son Guy was wounded while serving as a surgeon for Union regiments.

In October of 1870, tragedy struck when son James was killed in a railroad accident, having "driven a hog from the track and was in the act of mounting the platform," said the Preston County Journal. Another son was killed "on the railroad" at another time, but his identity is not known.

Later that year, Hiram himself died, on Dec. 4, 1870. He also allegedly was killed in a railroad accident. Almost 40 years later, the obituary of son Guy stated that Hiram died in such a way, but no confirming proof has been found. A search of the Journal has found no articles about Hiram's death, railroad-related or otherwise. The only other known fact is that family friend R.W. Monroe later said: "I recollect the circumstances of [Hiram's] death very distinctly, was at his house at the time, I remember the season of the year also very distinctly."

After Hiram's death, Catherine continued to operate the hotel in Independence, with the help of unmarried daughters Helen and Julia. Catherine remained close with her sister, Keziah (Miner) Martin, who had moved to Independence. Later, in about 1881, Keziah testified that:

…I have lived in Independence for about eleven years and during this time up to the death of [my sister], I was on very intimate terms with my said sister, often visiting each other often every week…. From personal observation I am well acquainted with how things were managed at the hotel which she kept during these said eleven years…. Especially from the time of the death of H.B. Hanshaw the two daughters [Helen and Julia] have managed and done most of the work to be done in the keeping of said hotel. In fact, from all that I could see and from what [my sister] would often say to me, I would say that it was really by the management and works of the two daughters … that all the real estate … was paid for, although I believe the purchase was made before her … husband's death. I know that these two daughters done all the house work about the said hotel except some of the cooking which was done by [my sister]….

[She] would often be up to my house and remain to near supper time when I would ask her to remain and I would get supper for and for her to stay for supper but she would always refuse and say that she must go home as there was no on e there but the girls … so that they could be free for awhile during the evening, as she wanted to give them a little pleasure so that hwy would still remain with her as she couldn't get along with out them. She would also say that she wanted everything to so work that she and the girls would get along well together as she couldn't get along without them and her interests should be theirs. She also would also often say to me, before she was taken with her last sickness, that these two girls … should be rewarded for the work and care they had done and given her.

Family friend Henry Fawcett also gave testimony that:

…A short time after the death of H.B. Hanshaw … [his widow Catherine] came over to my father's. My father was living in Independence, and wanted him to let me come and stay with her at the hotel. I went and remained there on and off the greater part of five years and from that time up to the date of Catherine Hanshaw's death I was there as a rule every week and often as much as four or five times in a week. During all this time I know from personal observation that Helen M. Hanshaw was at the head of the house … and did the business managing, as well as doing a part of the general housework there.

|

|

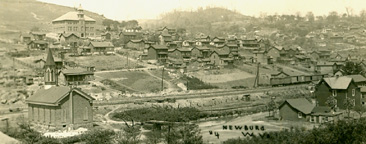

Bird's eye view of bustling Newburg |

Catherine passed away on Oct. 4, 1879, at the age of 65, at the home of her married daughter Jennie Huggins in Newburg. The Preston County Journal eulogized she "was one of the most aged and respected ladies of this country, and was loved and honored by all who knew her. Several months ago, she was prostrated with that dreaded enemy to the old Paralysis -- but improved somewhat, and was considered, at least, no worse until a short time previous to her death." The Journal added that:

…Her death will deeply grieve, although it will hardly surprise, the very large circle of intimate friends and aquaintances, who have been but too well aware for many weeks past that she could be spared to them but a short time…. She was an exemplary member of the M.E. Church, and universally esteemed for her kind and generous disposition. There are many beyond the limit of her relatives and immediate friends who will deeply sympathize with them and sincerely mourn her death.

|

Union Cemetery, Newburg |

Catherine was laid to rest at the Union Cemetery in Newburg. Her grave, near the large tree at upper right, went unmarked for many years. In 1884, when daughter Helen died, she bequeathed funds to purchase a marker. However, by 1910, the task had not yet been completed, and daughter Julia, who passed away that year, also left funds for this purpose, per the terms of her will.

(Also buried in this cemetery, according to the sign, were 21 men killed in the Newburg Mine explosion on New Year's Day, 1886.)

At the time of Catherine's death, she owed more than $1,500 to various creditors, including several of her adult children. Of the total, $95 was owed to Hanshaw & Bro. (the store run by her sons Charles and Robert in Grafton, WV), for debts accrued from 1876 to 1881. On credit, she had purchased such foodstuffs as sugar, ham, flour , coffee, syrup, beans, rice, apples, corn, salt, baking powder, peaches, pepper and bread, as well as such household items as shoes, calico, soap, slippery elm, buttons, gingham, slippers and cashmere. She also owed storekeeper G.A. Sickle $65.49 for many other cooking and household goods. The lists, found in the civil court records of Preston County, provide a view of what was needed to run the hotel business in the late 1870s. Copies are in the Minerd.com Archives.

After Catherine's death, the hotel property was sold at auction to her daughters, Helen and Julia, by a specially appointed commissioner, John H. Holt, of Preston County. The tract later was sold out of the family, to Thomas Herrington.

| Copyright © 2000-2004, 2006-2009, 2012, 2017-2018, 2021 Mark A. Miner |

Chronicles of Border Warfare images courtesy Matt Wilson |