|

Dr. James

'Weston'

Minerd |

|

Carson City Cemetery, Michigan |

Dr. James "Weston" Minerd was born the day after Christmas 1856, in Van Wert County, OH, the son of Uriah and Matilda (Bodle) Minerd.

Once a dentist, but forced by poor eyesight to return to a livelihood in agriculture, he was considered by one Michigan history book as "a progressive and energetic farmer" of Montcalm County, MI.

Weston's first wife, a talented writer and editor, divorced him in the 1890s, then went to Texas and became a pioneering reporter, reformer and columnist under the pen name of "Pauline Periwinkle" for the Dallas Morning News.

When he was age seven, in about 1864, Weston migrated from Ohio to Michigan with his parents and siblings, settling near Carson City, Montcalm County, MI. As a teen he proved to be an "invaluable assistant to his father in the strenuous labors connected with the clearing of the forest and rendering habitable the then wilderness," said the 1916 book, History of Montcalm County, Michigan, authored by John W. Sadef. As a young adult, Weston used the "d" in his surname, but later went by the simpler form of "Miner."

|

|

|

Weston's profile in the 1916 History of Montcalm County |

|

| Adventist Tabernacle in Battle Creek |

After Weston and his brother Perry heard preaching by a local exhorter of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, they began attending services regularly and became converts to this branch of Christianity. Their interest led to their parents and sister becoming curious and then accepting the teachings of the church. Their conversion story was told many years later, in 1935, in a series of memoirs by the sister of their brother in law Benjamin Franklin "Frank" Ayars, in the church newspaper, The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald:

One Sabbath, Elder Burrill announced a business meeting at a church member's

house for a week day. We all brought our lunches, and planned to spend the day.

When we arrived, there were these two boys. After we had had our morning

session, and our dinner was all spread out on a long table, we looked around for

those boys, to invite them to have something to eat with us. But we could not

see them anywhere. Finally I went out on the veranda, and spied them sitting

down by the house, in the sun, eating the lunch which they had brought. I

decided I would find out something about them, so I went out and spoke to them.

I found that their name was Miner. After talking about the weather for a few

minutes, I inquired, "Did you ever attend any Adventist services before

this?" Yes, they replied, "a Mr. Brackett held some meetings in our

schoolhouse, and we attended those. And when we heard there were meetings here,

we came on over."

The older of these two boys, James Weston Miner, later went to

Battle Creek and worked in the Review and Herald office. The boys had a sister,

also, who, during the time they were going to church, had been away. But when

she came home and learned about the true Sabbath, she accepted it.

Weston is known in 1875 to have subscribed to the official church newspaper, The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, for the sum of one dollar per year. He also donated $3.75 for church publications in 1875. Seen here is the Adventist Tabernacle in Battle Creek, a site Weston would have known very well.

After graduating from the high school in Ithaca, Gratiot County, MI, he attended college at Battle Creek, Calhoun County, MI, and completed his studies in 1881, at the age of 24. He then taught school for three years, from 1881 to 1884, in Montcalm and Gratiot Counties. In 1884, Weston accepted a position in the publishing office of the Review and Herald in Battle Creek and was employed there for 14 years as an electrotyper. During this time, he became attracted to his future wife, co-worker Sara "Isadore" Sutherland (1863-1916).

|

Isadore Miner |

~ Weston's First Wife, Sara "Isadore" Sutherland ~

On Sept. 4, 1884, at the age of 27, Weston married 21-year-old Isadore, by the hand of Rev. M.B. Miller of Battle Creek. Isadore who shared his professional publishing interests as well as his Seventh-day Adventist beliefs. She was a native of Battle Creek, Calhoun County, MI, and the daughter of Mason Montgomery and Maria L. (Tripp) Sutherland. Attending the ceremony as witnesses were Daniel M. Sutherland and R. Belle Warner.

Isadore was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), as her mother was a direct descendant of Revolutionary War soldier Jabez Chadsey, of Rhode Island, who drowned while defending the town of Newport, RI. She also was a great grand-niece of Gen. Nathaniel Green who made fame during the Revolution. Her father died during the Civil War, and she grew up without the presence of a stable father figure.

Isadore's years as a young girl were "more or less unsettled, being passed among relatives in various Michigan towns," said one biography. "Her school life was necessarily irregular, and was continuous only after the age of 11 years." During this time, said the Literary Century:

She had always shown a predilection for writing both verse and prose, and when at school had always been the one chosen for any part out of the ordinary in this line. She was chosen class poet, and also wrote the poem for the alumni association for that year. Her first efforts in writing for the press were for the Little Corporal magazine, when she was 9 years old, and at that age and a year later she carried off the prizes offered by the Detroit Commercial Advertiser for best compositions by children. Her first poems followed shortly after and won considerable editorial notice because of the unusually good character of the verse for one so young.

When her mother relocated to Dallas, TX to recover from poor health, Isadore remained behind in Michigan. She moved into the household of an aunt, Mrs. R.A. Worden, of St. Clair. Her mother later married again, to M.L. LaMoreaux, also known as "Franklin" LaMoreaux.

Upon her marriage to Weston in 1884, Isadore stepped away from teaching and went to work at the Review and Herald in Battle Creek with her new husband. She is known to have set type for music and proofread printer's proofs, and honed her ability to write. Later, she claimed she had supported herself entirely by herself during her marriage by "her own efforts in a literary way." During their first winter together, they made their home in the residence of Rev. Miller, who had married them, and his wife Ann.

|

|

|

Jefferson Avenue North in Battle Creek |

Reflecting the growth in her popularity, she was featured in a biographical profile in the May 1893 edition of The Literary Century magazine ("Columbian Souvenir Number"). Reported the Literary Century:

During her engagement with the Review and herald she wrote as the spirit moved for the various publications of the house, and afterward, at their solicitation, collaborated with Miss Myrta B. Castle on a series of children's books, chief among which are "Cats and Dogs," "All Sorts for Children" and "In Every Land." These books were hardly from the press before she accepted an association with Miss Emma L. Shaw, to assist Dr. and Mrs. J.H. Kellogg on their magazine, Good Health. The two years of Mrs. Miner's desk-mating with Miss Shaw were of inestimable value. This association with one whose pen was so trenchant, whose criticisms were so just and kindly, and whose insight into the field of letters was so keen, meant much to the younger woman. It was as when the master hand sweeps the keys and the whole instrument vibrates; for it was the first arousing of an ambition. As she became able to judge dispassionately and weigh her own abilities, Mrs. Miner became convinced that she was best suited to active journalism.

|

|

Dr. J.H. Kellogg's |

Her Literary Century profile went on to quote Isadore asking: "It is easier to hold an audience whose immensity precludes addressing any individual, and what audience so large as that reached by the newspaper? and what field affords greater possibilities? I consider newspaper work pre-eminently adapted to woman's talents."

|

|

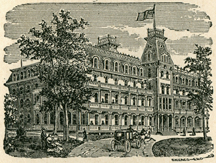

Battle Creek Sanitarium |

The Good Health publication -- which she joined in 1888 and was appointed associate editor in 1889 -- was a project of the innovator and entrepreneur Dr. John Harvey Kellogg. Isadore's name appears in the table of contents for the publication from December 1888 to October 1889, and perhaps longer. Among the titles of her writings for the influential magazine was the ongoing column "A Dear Experience" devoted to "temperance, mental and moral culture, home cultural, natural history and other interesting topics conducted by Mrs. E.E. Kellogg. Her byline also appeared under the headlines of her articles, giving her national exposure.

Isadore's boss Kellogg was a fellow Adventist, alumnus of a local publishing house and medical officer of the Adventist Church's Battle Creek Sanitarium. (The sanitarium building is seen here.) His sanitarium facility promoted a health regimen featuring vigorous exercise, a vegetarian whole-grain diet, abstinence from smoking and alcohol, limited sexual relations even among married couples and regular cleansing of the bowels. During this time working with the Kellogg family, Isadore became acutely aware of the need for improved health conditions for women and children, which undoubtedly shaped her outlook for the rest of her career. She remained at Good Health for two years.

[Kellogg and his brother may be best known for creating in 1906 the Kellogg Company, which later produced what became world-famous "Kellogg's Corn Flakes." One employee, Charles William Post, later defected from the concern and began producing a rival brand of cereals under the Post Cereals brand. Kellogg was portrayed by actor Anthony Hopkins in the 1994 Columbia Pictures film, The Road to Wellville, also starring Matthew Broderick, Bridget Fonda and Dana Carvey.]

|

|

|

Isadore's publishing boss John Harvey Kellogg, who later invented Kellogg's Corn Flakes; and as portrayed by Anthony Hopkins in the film, The Road to Wellville. |

Supporting her Seventh-day Adventist faith, Isadore donated $20 in early 1887 to a missionary effort to her ancestral homeland, Scotland. She also wrote essays for the church's Review and Herald including a series in 1885 on "Brief Biographies of Eminent Men" who had been instrumental in the Reformation, such as Eusebius, Martin Bucer, Paul Fagius, Peter Viret, Henry Bullinger, Patrick Hamilton and John Knox, among others. She also wrote poetry such as "Life's Questions (1885) and "Which Was the Taller?" (unknown date). On Christmas 1886, at services at the Adventist Tabernacle, said the Review and Herald, "An original poem by sister Isadore Miner, emphasizing the fact that the same Jesus who once appeared as a babe in Bethlehem, is again coming, and that soon, in power and glory, as Lord of lords and King of kings, completed the program."

|

|

| Poets of America book |

|

|

| Poets of America entry |

Three of Isadore's poems -- "Old Scores Repaid, or Tragedy Reversed" -- "The Little Young Man in Gold" -- and "I Don't Want to Go to Bed" -- appeared in the 1890 book, Local and National Poets of America, compiled by Thomas W. Herringshaw, seen here. Certainly unknown to her was that poems by two of her husband's distant cousins also were published in the same volume, Allen Edward Harbaugh, a cobbler living at Mill Run, PA, and Isham Gaylord Davidson, an insurance agent in Springfield, IL. In a brief profile of Isadore in the book, Herringshaw writes:

Graduating at the age of seventeen, this lady then took up the avocation of school teaching until her marriage in 1884 to J. Weston Miner. Her husband being connected with the Battle Creek Review and Herald publishing house, Mrs. Miner was engaged as a proof-reader, and finally as a writer, editing a large share of the work on a series of children's books issued from that office. Her poems have been widely published in St. Nicholas, Wide Awake, and the periodical press generally. She still follows the profession of editor and writer at Battle Creek, Mich., and is connected with the Good Health Publishing Company of that city.

Isadore's poem "The Little Young Man in Gold" was printed in the June 1889 edition of St. Nicholas, billed as "an illustrated magazine for young folks," published by Mary Mapes Dodge. She is alleged to have written all the stories and poems, and creating the page layouts, for two children's books produced in 1890 by Review and Herald Publishing. The titles are not known, and she may not have received any sort of byline credit.

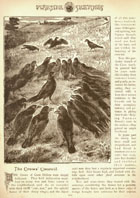

In 1890, some of Isadore's poetry was published on five different pages of the volume Fireside Sketches of Scenery and Travel. Some of the titles include "Crow's Council," "A Dip in the Brook," "What Next?" and "Our Pearl." Most of her works in this book were liberally illustrated with pen and ink drawings, but the artist's name seems to be lost to history. An original copy of this volume is preserved today in the Minerd.com Archives.

|

|

|

Isadore's liberally illustrated poems published in Fireside Sketches of Scenery and Travel -- "Crow's Council" - "A Dip in the Brook" - "What Next?" - "Our Pearl." Below: "Dodo's Recognition" printed in Wide Awake, February 1891. |

|

|

~Carson City's "Other" Miner Family ~

At the time Weston and his family lived in Carson City, another family of Miner, not related to our group, also made its home there. Originating with Anderson and Delilah Miner, came from Geneva County, New York State, having been granted a U.S. government deed in 1851. This no doubt created much confusion over which family was which. While Weston's parents and brothers generally used the "Miner" spelling, Weston and his sons may have continued the old Pennsylvania German "Minerd" spelling as a point of differentiation.

|

|

Carson City's |

Miner Road, a north-south road in Bloomer Township, is believed to be named for this "other" family of Miner. As well, "Miner's Addition" to the town is thought to be attributed to them.

Anderson and Delilah Miner had at least one son, Martin J. Miner (1837- ? ), who married Lucinda Hawley; and at least two grandchildren -- George H. Miner ( ? -1908), who in 1874 wed Martha Annette Yates; and Lucena Miner, who married T.C. Frushour. George and Martha's son, M. Jay Miner, is profiled in Dasef's history of Montcalm County. M. Jay Miner married Ola Thayer in 1906 and had five children -- Martha Louise Miner, Veneva Leone Miner, Velma Elizabeth Miner, George William Miner and Irma Lucille Miner (who died at age seven weeks). Dasef wrote that M. Jay was "one of the favorably known men of Bloomer township, ... being foremost in those things having for their object the advancement of the community's interest and being a citizen who lends freely of his time and effort for the promotion of various projects dealing with scientific agriculture and the betterment of general local conditions."

~ A Marital Separation ~

Isadore's years in Battle Creek honed her for her future work. She increasingly was recognized for her emerging views on women's rights, and was named the first corresponding secretary of the Michigan Woman's Press Association. She was talented, ambitious and eager to continue building her professional career, and growing ever disenchanted with her marriage.

During her years with Weston, she alleged, he refused to provide for her, and only purchased one dress for her over all of that time, valued at between $12 and $15. He also was envious of her friends, including other women whom he apparently believed exerted too much influence. She wrote that he "does fail and neglect to support and maintain her..."

In February 1891, ready to break her marital ties, Isadore accepted a post on the Toledo (OH) Commercial, which meant a move to a city some 120 to 130 miles away. Of this major transition, longtime friend Fannie Segur Foster later knowingly wrote: "Her talents were too brilliant to be hidden in a country village." While at the Commercial, over the span of two years, she wrote news stories.

|

|

|

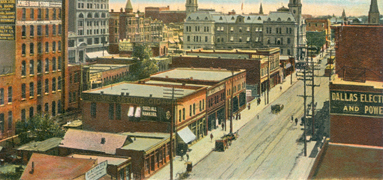

Bird's-eye view of Dallas -- Isadore's new home -- early 1900s |

|

Weston and Isadore's |

In 1893, still legally married, but living apart from her estranged husband, Isadore made a final and complete break when she accepted a more prominent reporting position in Texas. The offer came from the Dallas News and Galveston News, "two of the best known of metropolitan newspapers in the southwest" and operated by the same owner. Her specific responsibilities were as society and literary editor of the Dallas News, and woman's and children's editor of the News in Dallas and Galveston. Circa 1893, when the Literary Century profile was published, she was praised as having "placed herself in the front rank of women journalists in the south."

Isadore's mother was living in Dallas at the time, and after her step-father was brutally injured during a robbery, Isadore likely was drawn there to help provide support.

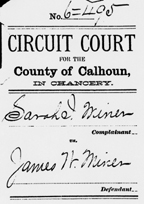

To deflect uncomfortable questions about her marital status in her early years in Dallas, Isadore told friends and colleagues that she was a widow when in fact she was still married. She filed for divorce in Michigan in July 1894, with the case assigned the official number 6-495. The papers are still referenced today in the Calhoun County Circuit Court, with the originals on microfilm at the Archives and Regional History unit of Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo.

Isadore filed her legal complaint on July 24, 1894, and a subpoena was served on Weston two days later. He failed to respond within the proscribed 20 days, and so seemed to be consent to allow the divorce to proceed. Among the witnesses testifying in court on Isadore's behalf were Anna Miller, wife of the minister who had performed the ceremony; Myrta Castle, who worked with Isadore a a proofreader and writer; and Emma L. Shaw, associate editor and proofreader of the Good Health publication.

~ Weston's Brief Dental Career ~

Now divorced, and pursuing his interest in a career in the medical field, Weston at the age of 41 graduated from the University of Michigan College of Dental Surgery in 1898. Following graduation, reported the university's Dental Journal, he "will devote his spare time during the summer vacation practicing in Battle Creek..." He was named in May 1897 to the board of editors of The Dental Journal of the Dental Society of the University of Michigan.

He enjoyed bicyling but suffered a casualty in early April 1897 "while taking a spin," said the Dental Journal. "He was run into by another wheelman and suffered a compound fracture of the outer third of the right clavicle. The forward wheel of his bike was simply comminuted." While he complimented his physicians Dr. Nancrede and White, who treated the fracture, and a Mr. Tucker who fixed the wheel, he admitted that it "almost tempts him to a repetition of the acrobatic feat, but as he still carries his arm in a sling, perhaps he has changed his mind."

The federal census of 1900 shows Weston as single and marked "divorced." He made his home that year with his brother and sister in law, John "Perry" and Sarah E. (McAllister) Miner, on Kendall Street North in Battle Creek. Also in the residence that year was Perry's father in law, William McAllister, a native of Ireland. Weston's occupation was listed "dentist" and Perry's as "packer (food factory)." Remarkably, the census taker made a point of spelling Weston's name as "Minerd" and Perry's as "Miner" in their side by side entry on the very same record.

Weston apparently was hired by the university in about 1901 to teach as a "Demonstrator of Operative Dentistry." His salary, as published in the Regents' Proceedings, was $400.

~ A Second Marriage, to Ola Hall ~

On July 25 or 31, 1901, in Battle Creek, Weston married his second wife, Ola J. Hall (1880- ? ). Rev. Erwin Evens, a minister of the Gospel, performed the ceremony. Elder Abbott also may have been involved in the wedding. Ola was a native of Iowa who was 24 years younger than Weston. She was the daughter of James M. and Flora (Murdock) Hall, who later lived on a farm near Chattanooga, Hamilton County, TN.

The Miners had no children of their own, but adopted twin sons of the family of Frank and Ada Dunn -- John Dunn and Robert Dunn -- born in either Georgia or Tennessee. (Robert later claimed it was "Tennessee.") Their father was dead, allegedly a victim of World War I, and the Minerds received $9 per month in pension payments for their support. John was re-named as "John Dunn Minerd" and then later as "Herbert Weston Minerd," while Robert was renamed as "Robert Dunn Minerd" and later as "Robert Milton Minerd."

Circa 1904, Weston maintained his "dental parlor" in his home at 229 Main Street in Battle Creek. He is listed in that year's edition of the Battle Creek Business Men's Commercial Reports. He was credit-rated by two fellow merchants as prompt in paying his bills in moderate amounts.

Unfortunately for Weston, his eyesight began to fail in 1904, just a few years into his dentistry career. Abandoning the practice which he had been building, he and Ola moved for a brief period to Chattanooga to be near Ola's parents. Said the History of Montcalm County:

He then went to Chicago, where for five years he was actively connected with the great publishing house of Rand McNally & Company. At the end of that time, in April, 1909, he returned to his old home in this county and, in order to relieve his father of the cares of the farm, advancing years by that time having begun to leave their trace upon the robust figure of his pioneer father, bought the old home place and has since that time been very successfully operating the same, making his home there... Doctor and Mrs. Miner take a proper part in the social activities of their home neighborhood and are held in high regard thereabout.

When the federal census was taken in 1910, Weston and Ola resided on the 80-acre farm of his parents along Rural Route 2, with Weston working as a farmer. A local rural directory of the era shows that they owned four horses and five head of cattle.

|

|

Typical Carson City farm scene, early 1900s |

Seen here is a typical Carson City farm scene, with a cow grazing along a nearby creek. Circa 1910, a total of 4,678 farms were operating within the 724 square mile Montcalm County. The largest single local crop was potatoes -- in 1910 more than 2.2 million bushels were produced. Other vital crops produced in the region were corn, oats and wheat.

The living arrangement was disastrous as Ola often clashed with her husband and his sister and mother in law. She claimed that they refused to let neighbors into the home to visit with her, even when she was sick. Weston stopped taking her to worship services after two years, complained about her behavior in church and forbade her to go to town without stopping at his mother's home first.

Later, when suing for divorce, Ola claimed that Weston was violent and had an "ungovernable temper" but that her husband's mother:

... told [Ola] she was too young for Weston ... that had she know of it the wedding would not have taken place, she accused [Ola] of having a baby before her marriage, accused her of lying, accused her of holding her head too high, circulated false statements about her among the neighbors, disliked to have her meet the neighbors, told [Ola] the neighbors did not want to see her, told her to keep her mouth shut, the sister [Sarah Caroline Ayars] openly boasted that the mother and she had got Weston ... to do as they wanted him to do, notwithstanding that [Ola] continued to work and slave for the family and help furnish the home and aid her to gain a competence she was treated as a menial and not accorded her proper place in the home by [Weston] or his family whom he failed to reproach for their inhuman conduct toward [her].

By 1920, the census shows the family in Bloomer Township near Carson City, Montcalm County, with Weston again engaged in farming. Their homeplace was along Red Bridge Road.

Faced with an unsafe home environment and crumbling marriage, Ola moved out of the Minerd home on June 26, 1924, and sued for divorce. Having heard arguments from both sides, the court ruled that Ola's allegations were materially true, and that Weston was unsuitable to raise their children. The marriage was dissolved by court order on Nov. 12, 1924. She was given possession of all rugs, dishes and carpets; dining room linoleum; rocking chair; bed with mattress and springs; all cans and fruit jars; one washing machine; one wash tub; and one-half of the bed quilts. Weston also agreed to provide Ola with an IOU for $1,000, payable within four months, that would release him from all future legal claims she might file.

Ola is known to have married a second time, on Jan. 12, 1925, to W.F. Keith (1860- ? ) of Carson City. They moved to Flint, Genesee County, MI. By 1938, Ola is known to have been admitted to the psychopathic ward of Hurley Hospital in Flint. Her final fate is unknown.

|

| Carson City landmark today |

~ Weston's Final Years ~

When the federal census was taken in 1930, the twice-divorced, 73-year-old Weston made his home with his 94-year-old mother and 75-year-old widowed sister, Sarah Caroline "Carrie" Ayars, on Maple Street in Carson City, Montcalm County. The lot measured 154 ft. by 110 ft. in block 6 of Miners' Addition to the village.

In his final years, Weston suffered from senility and from chronic cardio-vascular disease and kidney failure.

Weston passed away in the village of Carson City at the age of 89 on or about Dec. 14, 1945. If he had lived another 15 days, he would have celebrated his 90th birthday. He was laid to rest in the Carson City Cemetery.

An inventory of his possessions shows that he owned small carpentry tools and a vise, bed spring and mattress, dresser, book case, round table, rocking chair, books and one bed blanket. Financially, he held a note receivable from the Michigan Produce Company in Carson City valued at $1,890, and his town lot was worth $1,000.

Oddly, Weston's death certificate and probate papers, on file today in Montcalm County, state that he was the widower of "Isadore Minerd" and not of "Ola Minerd" or anyone else. As Ola's son Robert would have been the informant, this seems particularly unusual.

|

Her biography |

~

Isadore's Transformation into Pioneering

Dallas Journalist "Pauline Periwinkle" ~

After arriving in Dallas in about 1893, Isadore began to reinvent her life completely as a "writer, social welfare worker and club woman," said the Dallas Morning News. Before she appeared on the scene, "Texas newspapers offered only fashion and social news to their women readers," said a review by Texas A&M University Press. Writing under the pen name "Pauline Periwinkle," she penned a regular column that "changed all that, encouraging women to take part in the reform efforts of the Progressive Era."

Her accomplishments were so influential that more than a century later, her life was featured in a full-length biography, Pauline Periwinkle and Progressive Reform in Dallas, authored by Jacquelyn Masur McElhaney and published by Texas A&M University Press.

During her 23 years in Dallas, until her death in 1916, Isadore was sought for membership and leadership in myriad community, charitable and humanitarian causes. While she declined some -- citing potential conflict of interest with the objectivity of her role with the newspaper, she accepted many others. Among them were the Texas Woman's Press Association, Texas Equal Rights Association and Woman's Congress.

Elizabeth Brooks, writing in her book Prominent Women of Texas, said Isadore was the "only woman in Texas who has ever been honored by a temporary seat in the presidential chair of an assembly composed exclusively of men... The Texas Press Association was the source of this compliment, and her reading of an appreciated paper before that body was the occasion."

|

|

|

Isadore's profile in the 1896 book, Prominent Women of Texas |

|

|

|

Book naming Isadore |

At the invitation of the president of the Texas Federation of Women's Clubs, Isadore attended a meeting in April 1898 and provided advice on how to expand the organization's publicity, which "was to have an important bearing upon the progress of the federation, and opened up one of its greatest factors for success... [She] addressed the body regarding the publication of its official organ, and suggested that a club editor be appointed to collect and compile official club news, to be published through the great dailies of the state," said the 1919 book, History of the Texas Federation of Women's Clubs, authored by Stella L. Christian. "'A motion to reconsider the publication of the club monthly and adopt Mrs. Minor's [sic] suggestion was adopted.' Mrs. Kate Scurry Terrell, Dallas, was elected the first editor, and all power to act in regard to this matter, placed in the hands of the Executive Board."

|

|

Dallas Public Library, opened in 1901 |

Said McElhaney in Pauline Periwinkle, Isadore reported on and actively supported Dallas efforts to:

... secure a Carnegie Library, kindergartens for public schools, a juvenile court system for the city, parks for children, a local pure food law, police matrons, a garbage tax, and a pure water supply. Statewide efforts for such measures as a pure food and drug law, a women's college, and woman suffrage received her incisive coverage. Other columns would describe efforts by women's clubs in cities across the country, the difficulties endured by working women and children, the desirability of electing women to school boards, and the need for higher education for women.

Among her most lasting achievements was a collaboration with other civic leaders to attract Pittsburgh industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to donate funds for a Carnegie Public Library in Dallas. On March 30, 1899, two years before the library was built, she served as secretary of the inaugural public meeting of the Dallas Public Library Association. She is pictured in the library's official history, The Dallas Public Library, authored by Michael V. Hazel, and mentioned on several pages for the newspaper columns she wrote promoting the need for such a cultural resource. The impressive library building, as opened in 1901, is seen here.

In July 1900, after seven years in Dallas, Isadore married William Allen Callaway, a onetime journalist who had become successful in the insurance field. The ceremony took place in Washington, DC. From thence forward her professional name was "Isadore Miner Callaway." They spent their honeymoon in Europe, where Isadore visited her Sutherland ancestral home, and wrote dispatches back to her newspaper. Later they "established a beautiful home, where simple and cordial hospitality was the rule," said the Morning News.

|

|

|

Books mentioning Isadore's groundbreaking contributions to important public affairs -- 35,000 Days In Texas, by Sam Acheson; The Dallas Public Library, by Michael V. Hazel; and Women and the Creation of Urban Life, by Elizabeth York Enstam |

|

|

Isadore's photo,

Who's Who |

Isadore is seen here during her Dallas years, as published in the 1924 book, Who's Who of the Womanhood of Texas by the Texas Federation of Women's Clubs. She covered routine news for three years until offered her own weekly column, "The Woman's Century," the first of which appeared in print on April 15, 1896. The early days of Dallas life were challenging, as Isadore often had to travel to outlying towns and communities to gather her news. Wrote friend Foster: "Her sense of humor and her cheerful attitude toward life made even this work a pleasant game." She and colleagues were known for "wading through the mud of unpaved streets and frequently standing, soaked with rain, on a corner, waiting for the bell of the infrequent street car, then drawn by two sleek mules and stopping anywhere signaled, and for any length of time the patron needed or wished, for adieus of visits with the departing friend."

|

Book naming Isadore |

For scholars interested in reading her newspaper columns, a list of key dates in which she published columns dealing with women's rights and suffrage is listed in the book, Citizens At Last: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Texas, an essay by A. Elizabeth Taylor (1987: Ellen C. Temple, publisher).

Her articles often were reprinted in other, important journals. She also wrote on a freelance basis for such publications as Little Ones and the Nursery, as well as influential newspapers. "Some of her work has been copied abroad," said the Literary Century, "and one article in particular appeared in a leading German magazine, contributed by a well-known literateur of that country, and translated as 'the best specimen of pathos by recent American writers'."

Isadore died at the age of 53 on Aug. 10, 1916, triggering an outpouring of public affection and praise in local newspapers and the community at large. She was laid to rest in Oakland Cemetery.

The fate of her second husband W.A. Callaway is not yet known.

|

Isadore Miner Callaway's Known Writings In Other Journals |

| "Women's Work in Education," The School Journal, Aug. 18, 1906 | Texas Medical Journal, 1913, quoted |

| Kindergarten Magazine, Feb. 1897, quoted | "The Mental Divertisments of the Farmer's Wife, Farmer's National Congress, Nov. 10-13, 1896 |

| "Dodo's Recognition," Wide Awake Magazine, February 1891 (poem) |

~ Son Herbert Weston Minerd ~

Son Herbert Weston Minerd (1910-1982? ) was born on March 6, 1910 in Chattanooga, TN.

He stood 5 feet, 7 inches tall in adulthood and weighed 180 lbs. His eyes were blue, his hair brown and his complexion light, with a mole under his right eye. He wore false teeth.

At the age of 31, he was required to register for the military draft during World War II. At the time, he was married, unemployed, and their address was 801½ Newall Street in Flint, Genesee County, MI. He disclosed that his mother in law Grace Luxton would always know his location.

He resided at 725 Broadway in Flint in 1945.

Herbert is believed to have died on Christmas Eve 1982 in Flint, at the age of 72. His remains are at rest in Flint Memorial Park.

~ Son Robert Milton Minerd ~

Son Robert Milton Minerd (1912-1969) was born on March 6, 1910 or 1912 in Georgia or Tennessee. He grew up in Carson City, MI.

He lived circa 1930 in Washington Township, Gratiot County, MI, boarding as a farm laborer with the family of James and Mary Van Alstine.

He stood 5 feet, 9½ inches tall and weighed 210 lbs. His eyes were blue, his hair brown and his complexino ruddy. He spelled his name "Minerd" in adulthood.

Robert was joined in the bonds of wedlock with Donna C. Simons (1916-1985).

The couple produced three sons -- Ralph Lavern Minerd, James Weston Minerd and Robert "Gene" Minerd.

Circa 1940, when the federal census was taken, Robert and Donna made their home in Flint, Genesee County, with Robert employed as a laborer in a warehouse. When registering for the military draft during World War II, he disclosed that their address in Flint was 1003 Cedar Street and that their telephone number was 2-1754. At the time, he was employed by General Foundry on Hempfield Road in Genesee. He also stated that his brother-in-law Evan Simons would always know his whereabout.

|

|

|

Robert (2nd from right) with sons, L-R: Gene, Jim and Ralph |

Circa 1945, when his father died, Robert made his home in Carson City, and signed official papers related to the estate.

He died at age 57, on Nov. 26, 1969, with burial in Carson City Cemetery. He is believed to rest in the same lot as his father, but the grave is not marked.

Donna survived him by 16 years. She passed away in September 1985, in Davidson, Genesee County. She was buried beside her son Ralph at Eastwood Colonial Memorial Gardens in Davidson, Genesee County.

Son James Weston Minerd (1935-2003) was born on Jan. 16, 1935 in or around Flint. He was a Navy retiree and Vietnam War veteran. He married Laura Jean Hutchinson ( ? - ? ) and resided in Santee, CA. At the age of 68, he died on July 14, 2003 in San Diego, CA. The obituary in the San Diego Union-Tribune named his children as Kim Floyd of Pendleton, KY; Ramona Shaw of Salt Lake City; Anthony Minerd of Rochester, WA; and James Minerd of Albuquerque.

-

Granddaughter Kim Floyd of Pendleton, KY

-

Granddaughter Ramona Shaw of Salt Lake City

-

Grandson Anthony Minerd of Rochester, WA

-

Grandson James Minerd of Albuquerque, NM

Son Robert Eugene "Gene" Minerd (1937-1990) was born on Oct. 30, 1937 in Flint, Genesee County. He was joined in the bonds of wedlock with Janetha Gayann "Gay" Wheatley (June 27, 1939-2020), daughter of Curtis and Genevieve (Miller) Wheatley of Flint. The couple lived in Mayville, MI and produced these offspring -- Dawn Valentina Minerd, Michell Minerd, Michael Minerd, John Minerd, Jeff Minerd and Coreena Minerd. Robert was in Arizona at the start of the year 1990. He suffered a massive heart attack and died on Jan. 13, 1990. Gay married again in October 1996 to Leo Graves ( ? -2004). He had been married previously and brought a number of children to the second union. Sadly, after eight years of marriage, Leo succumbed to death in August 2004. Gay spent her final years in Montrose, MI. She died at home at the age of 81 on July 18, 2020. Her remains were cremated.

-

Granddaughter Dawn Valentina Minerd

-

Granddaughter Michell Minerd was married to or a companion of Russ.

-

Grandson Michael Minerd married Denise.

-

Grandson John Minerd wedded Mattie

-

Grandson Jeff Minerd

-

Granddaughter Coreena Minerd

|

|

|

Ralph L. Minerd |

Son Ralph Lavern Minerd Sr. (1939-1980) was born on Oct. 19, 1939 near Flint, Genesee County. He married Phyllis Ann Filkins (1940-2013), daughter of Joseph and Hattie (Burks) Filkins, on May 19, 1962. They resided in Columbiaville, Richfield Township, Genesee County, and had a family of children -- among them Joseph "Joe" Minerd, Ralph Lavern Minerd Jr., Donna Minerd, Pam Minerd-Osgood and Debra Martinez. Circa 1980, Ralph was employed by Richfield Disposable as a dump truck driver. Tragedy struck three days into the new year at 2 a.m. on Jan. 3, 1980, when 40-year-old Ralph was driving his truck in the Saginaw area. He was one of two men killed in cold blood by a gang of three who were shooting out windows of vehicles, intent on harassing blacks. The blast from the shotgun fired by a 15-year-old assailant struck Ralph in the eye, killing him instantly, with the truck careening off the road. His remains were laid to rest at Eastwood Colonial Memorial Gardens. Numerous news reports about the shootings characterized the killings as "wanton," "homicidal craziness" and a "drunken 'spur-of-the-moment whim'."

|

Ralph and Phyllis, wedding day |

The underage shooter was apprehended and convicted. On Aug. 26, 1980, he was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole by the Saginaw County Circuit Court in the case Michigan vs. Richard Musselman. In a twist of the story today, Michigan legislators are attempting to change criminal law involving youths under age 17 who no longer would have to serve life in prison if convicted. With the possibility growing that Ralph's killer could be set free, one of Ralph's daughters has testified about her views before the Michigan Attorney General. The case may be heard by the Michigan Supreme Court. Phyllis later wed Clyde Coon. She made her home in Columbiaville. After suffering from diabetes, she passed away at the age of 72 on Feb. 13, 2013. Her obituary was published in the Flint Journal, which said she was survived by a dozen grandchildren.

-

Grandson Joseph "Joe" Minerd was joined in wedlock with Trenda.

-

Grandson Ralph Lavern Minerd Jr. was united in matrimony with Jeanette.

-

Granddaughter Donna Minerd is the mother of McKenzie Minerd and Andrew Minerd.

-

Granddaughter Pam Minerd married Denis Osgood

-

Granddaughter Debra Minerd wedded Nadav Martinez.

|

Copyright © 2008-2014, 2018 Mark A. Miner |

|

Sketches of John Harvey Kellogg and the Battle Creek Sanitarium originally published in Kellogg's book Plain Facts (I.F. Segner, Burlington, Iowa, 1884). Road to Wellville image courtesy of Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. (photo by Merrick Morton). Image of S. Isadore Miner Callaway in Dallas courtesy of Don Brownlee. Robert Milton Minerd family images from Donna Minerd. |