|

Allen

Edward Harbaugh |

|

Al-Ed-Ha |

Allen Edward Harbaugh was born on July 7, 1849 in Normalville, Fayette County, PA, the son of Leonard and Maria E. (Eicher) Harbaugh Jr. He was a turn of the 20th century Renaissance man, poet, journalist, sketch artist, sign painter, historian, economic development champion and political analyst. His home was Mill Run, Fayette County, in the years before it became famed as the home of Fallingwater, the nation's most famous modern house. He was nicknamed "The Mountain Poet" and his pen name was "Al-Ed-Ha," an abbreviation of his full name.

|

|

|

Magazine cover, 1999 |

Allen was the cover subject of a 1999 issue of Western Pennsylvania History Magazine, published by the Senator Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center, and sold in newsstands all throughout the city.

Beginning in the 1860s, when he learned the trade of printing and his word and math puzzles appeared in a children's magazine, Harbaugh's name was known throughout the Fayette County coal region, and at times beyond. His works were published in newspapers, books and magazines, and at his death, the Pittsburg Press and Pittsburg Gazette Times both called him the "Mountain Poet" and noted his work as an editor.

As an artist and sign painter, "nobody was better known in the Connellsville region," eulogized a Fayette County newspaper. "Buildings, barns, fences, rocks and signboards from Uniontown to Mount Pleasant bear evidence of his skill."

His history of our family, written in 1913, has been an irreplaceable source of information that we otherwise would not have, and led to many other new discoveries.

Harbaugh loved the public spotlight -- but the irony of his achievements is that his myriad talents were played out to an audience primarily of laborers and their families who made their livings on farms, railroads and coal fields, and who may not have fully appreciated his skill.

|

|

|

Allen Harbaugh |

In the eight-plus decades since Harbaugh's death, while he has faded largely from public memory, his works at times have resurfaced and have been published in local histories, a testament to the staying power of his creativity.

Since much of his art has been lost in the passage of time, perhaps his story will provide readers with an understanding of his massive body of creativity, and lead to the discovery of other lost works.

~ Harbaugh's Work in Context with His Industrial Community ~

Fayette County is famed for its vast deposits of soft coal, which was burned into virtually pure cakes of carbon (coke) at batteries of local ovens. The coke then was shipped by rail to Pittsburgh for use as high-grade fuel in the steel mill blast furnaces.

Uniontown historian Walter "Buzz" Storey says the pinnacle of the coal and coke age was "hectic, brawling and sometimes sad but mostly glorious..." Workers could earn a meager wage without needing any education other than on-the-job training. Literacy and art appreciation were not universally valued, and while Harbaugh loved his visibility, locals perceived him as both a source of pride and as an oddity.

|

|

|

Fayette County coke oven operations |

Perhaps to stand out in such a hard-edged society, and to satisfy his immense ego, Harbaugh was prolific in his writing, drawing and painting. To add emphasis to his image, he often wrote his name prominently on the billboards and barns he decorated, and in the corner of his sketches. His signature flowed in large scrolled writing, often with bric-a-brac swirls all around in ink combinations of black, red and blue.

Harbaugh's artistry did not produce enough income to sustain him and his family over the years. His base source of income, which sustained him during the up-and-down cycles of commissions, especially during the winters, was shoe and boot making. The craft was handed down in the family, and basically the business was a one-man proprietorship. In 1875, when Harbaugh took over his father's small shop in Mill Run, the Genius punned that he was "doing good for men's 'soles'."

~ Personal and Family ~

Allen was raised as an only child, until he was 16 years of age. In 1865, his parents brought into their home a foster son, Samuel Martin, who was renamed "Ulysses Grant Harbaugh." The boy was legally adopted by the Harbaughs in 1875. This no doubt caused Allen much envy, as he later often referred to himself as his parents' only "natural-born son." Adding insult to injury, Allen and his brother had birth dates one day apart (July 7 and 8) which no doubt meant sharing the spotlight of birthday celebrations.

At the age of 28, on Nov. 22, 1877, Allen was united in the bonds of holy matrimony with 24-year-old Margaret Williams (Aug. 3, 1853-1921) of Ohiopyle, Fayette County, the daughter of Rev. John and Elizabeth (Galloway) Williams. In an interesting twist, Allen's uncle Joseph Harbaugh married Margaret's sister Jane, and Allen's cousin Jonas Rowan wedded another of Margaret's sisters, Julian.

The couple bore three sons and two daughters -- Chauncey Clinton Harbaugh, William Judson Harbaugh, Rev. John Austin Harbaugh, Annie Elizabeth Harbaugh and Emma Catherine Harbaugh.

|

|

|

Left to right: William, Annie, Emma and John |

Over the years, while trying to broaden his income with other ventures, Harbaugh's basic source of livelihood was shoemaking.

When the federal census was taken in 1880, Allen and Margaret and sons Chauncey (age 1) and William (3 months) lived in Stewart Township. Living under their roof was Allen's 43-year-old, unmarried cousin Annie Leonard, who may have been staying there to help with the young children.

In 1915, the year before he died, Allen wrote a short testimonial for the self-help book entitled Power of Will, by Frank Channing Haddock, Ph.D. The volume was billed as the "only book in the world today offering a scientific, elaborate instruction system in Courage-power. It has transformed the most abject, cringing, unreliant people into magnetic, confident success-winners." Allen's testimonial simply read: "Have already achieved certain victories worth far more than the book cost."

|

|

|

Our Schoolday Visitor |

~ Sketch and Puzzle Artist ~

Harbaugh was a self-taught pen and ink artist, underscoring the depth of his talents. Surviving sketches show that his style was what we today call a "folk artist." His figures of people and buildings, though generally lifelike, were not always in perspective or in proportion to their surroundings.

Nonetheless, his works were well-received. Connellsville's Courier and Uniontown's Genius covered his activities and referred to him in such glowing terms as a "young and rising artist" and "an excellent sign painter."

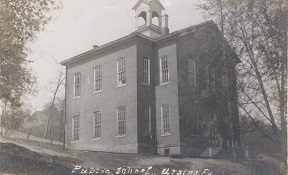

He drew many pictures over the years, but most are lost. His first published work in 1867, when his sketches began to appear in Our Schoolday Visitor, a children's magazine published in Philadelphia. How Harbaugh landed this assignment is unknown. The first sketch in our archives was printed in 1869, a drawing of a rebus.

|

|

|

Our Schoolday Visitor masthead |

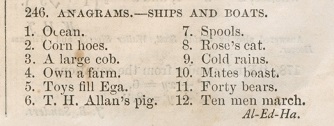

According to a profile of him in the 1890 book, Local and National Poets of America, within "a few years [he] was known the world over as the most expert author of anagrams and palindromes."

In mid-August 1884, he visited the office of the Keystone Courier in Connellsville, and displayed his work to some of the news staff. Reported the Courier, he had:

... interested the entire office in a cartoon of his own design, that would do credit to [Thomas] Nast. It represented the republican party after next November, suffering from a chill-Blaine. An immense fat leg with a swollen foot turned up, the sole of which was the face of Blaine. Cleveland stands in the rear writing a prescription. It is artistically gotten up and shows an aptitude for something higher than the shoe bench.

|

~ Our Schoolday Visitor Imprints 1869-1870 ~ |

||

|

On the pages of Our Schoolday Visitor, Harbaugh is known to have published pictures and riddles in the following issues:

1869: April ("Anagrams.--Days"); May ("Geographical Rebus"); July ("Anagrams.--Geographical Names" [unsigned]; August ("Puzzle); September ("Anagrams.--Ships and Boats"); October ("Anagrams - Precious Stones" and "Illustrated Rebus"); November ("Anagrams.--Geographical Names"). 1870: January ("anagrams upon geographical names"); February ("Anagrams upon names of countries"); May; July ("Anagrams--Scenes from Shakspeare"); August ("Illustrated Rebus.--No. 1" [unsigned] and "Illustrated Rebus.--No. 2" and "Anagrams--Scenes from Shakspeare"); October ("Illustrated Palindrome"); November ("Palindromes"); and December ("Anagrams--Quaint Books"). |

|

Hill Farm Mine sketch, 1890 |

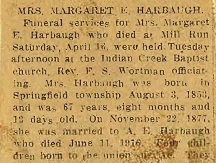

Among his other known works are two sketches he made of a coal mine disaster in 1890, after an explosion in Dunbar, Fayette County, PA killed 31 miners. Harbaugh was in Dunbar painting signs at the time, and he joined worried crowds to watch smoke spewing out the mouth of the Hill Farm Mine. For days and weeks, rescue teams removed tons of coal, slate and rock, trying unsuccessfully to reach the doomed men. The region waited in suspense for the gruesome outcome, as reflected by extensive newspaper stories.

Today the scene would be covered by TV crews and news photographers. But in his day and age, Harbaugh knew that a drawing, and not just words, could convey the horror. He set up an easel and began sketching in oil, crayon and ink. The Uniontown Herald noted his presence "as he stood on the high bank outlined against the sky... Crowds gather around his canvass and praise his efforts."

One sketch showed the mine's entrance the day after the explosion, billowing out clouds of smoke. Another sketch depicted the huge fan at the man-way of the nearby Mahoning Mine, blowing out poisonous fumes. Photo prints were made and sold at Porter's Art Store in Connellsville, and have turned up today in various individual collections. It has been reproduced in books such as the Dunbar Historical Society's Dunbar (Images of America series, Arcadia Publishing, 2009).

|

|

|

"Man-way of the Mahoning Mine" sketch, 1890 |

|

Hill Farm Mine sketch on display, 2002 |

The Hill Farm sketch also was displayed in September 2002 at the Dunbar Community Fest, from the collection of George and Donna Myers of the Dunbar Historical Society.

Harbaugh was commissioned to do many other drawings. During that era, before movies and television, lectures and debates were highly popular forms of entertainment. In fact, Carnegie as a young man organized a debating society in Pittsburgh to weigh issues of the day. In 1896, when Dr. Adam Deitz did a series of lectures in Mill Run on inhumane prison conditions, he hired Harbaugh to illustrate the talks with "a number of most striking views and scenes."

~ Sign and Decorative Painting ~

Another of Harbaugh's talents was painting advertising signs, prized in an age when alternatives were unavailable or unaffordable. He traveled to many towns in Western Pennsylvania to paint billboards and buildings, and to decorate homes and churches. The Genius once said that "Al-Ed-Ha has no superiors in that sort of work." The Connellsville News said that his "signs are fast getting a reputation for their originality," with Connellsville serving as his work headquarters. From Connellsville, said a national trade journal, The Billboard, "he radiates to points along the railroad lines, lettering walls, roofs and large boards provided for the purpose."

Such hand-lettered work was prized in an age when alternatives to hand-painted signs were unavailable or unaffordable. He traveled to many towns in Western Pennsylvania to paint billboards and buildings, and to decorate homes and churches. Sign-painting was big business, and he belonged to trade associations and wrote articles for related industry publications.

One of Harbaugh's biggest customers was "The Famous" department store in Connellsville, the first of its kind in the town. Owner Morris Kobacker awarded Harbaugh the first of several annual commissions in 1897 to paint billboards for "The Famous," using large fancy lettering to name products and prices. One was in six colors on Peach Street, which the Courier said "presents an appearance equal to those of the larger cities. Business men should visit the spot and get a hustle on."

|

|

|

Harbaugh's billboard work for Kobacker's Department Store, Connellsville, signed at the bottom right hand corner |

|

Harbaugh-decorated outbuilding |

Billboards today, for instance, are mass-produced and easily assembled, but at the turn of the century they were painstakingly lettered in hues of hand-mixed paints. While few of Harbaugh's signs and paintings are known to exist today, his grandson William Graden Harbaugh vividly recalls seeing murals of hunting dogs on the walls of the family house that Harbaugh mixed in bright colors and that lasted for decades.

Harbaugh received a large commission in 1885 to paint a huge advertising sign for George W. Campbell's general store in Normalville. The sign measured 70 feet in length and sat along what is now Route 711. In another commission in 1895, he painted a life-sized Indian on the front of the Independent Order of Red Men Hall in Mill Run. A large sign he painted on the side of Stickel's Store (later Livingston's Store) in Mill Run remained for years and depicted an owl with the caption, "We never sleep!"

|

|

|

Trade magazine

with |

In July 1885, Harbaugh was paid for an old sign-painting debt by Daniel F. Beatty, receiving an organ which he then sold to Evans Bigam for cash. The organ, said the Courier, "is first-class in tone and power."

He contributed stories to trade publications such as The Billboard (seen here), a Cincinnati journal on sign painting, bill posters and advertising. His articles typically included examples of the power of painted signs.

In 1898, Harbaugh's spiritual home, the Indian Creek Baptist Church at Mill Run, was formally rededicated after a major facelift. The labor was donated by members, and Harbaugh frescoed the ceiling and painted and "grained" the woodwork. (Graining is a painting technique to simulate wood grain.) The Courier said his figures were "altogether a fine bit of workmanship. The frieze is an arabesque of blooming daisies, and the centerpiece is a floral design of a large wheel enclosed within a square bordered with daisies and roses. The other works of the artist are in perfect harmony with the surroundings."

Many of Mill Run's older residents interviewed in recent years had a favorite Harbaugh story to tell. The late Carl Skinner of Mill Run recalled that Harbaugh strove to have sign painting accepted as an art, and bristled when locals inevitably poked fun. Skinner said that one local man, seeing Harbaugh at work, remarked, "I see you're doing some daubing," to which Harbaugh retorted, "I'll have you know I'm a professional painter!" One year he was appointed to the Committee of Arrangements for the Meeting of the National Sign Painters' Alliance in Cincinnati, Ohio, held in conjunction with the National Association of Master House Painters and Decorators.

|

|

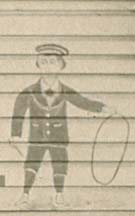

| Above: detail of Harbaugh's lettering and figure painting at Anderson's Cash Clothing Store, location and date unknown. Below: Harbaugh's signed name appearing right above the front door |

|

|

|

Harbaugh-decorated store |

One of Harbaugh's commissions is particularly illustrative of his abilities. At a date not yet known, he was given a contract to paint signage on the front of Anderson's Cash Clothing Store, also known as "Anderson's One-Price Cheap Cash Clothing Store." Not only did he letter the store's name in several locations, in different fonts, but also created figures of a well-dressed man and boy. (The sketches of the man and boy are not drawn to true human proportion and reflect the artist's folk style.)

He even lettered his own name, "A.E. HARBAUGH," directly above the front doorway, and below the words "One Price Store." His clients were so pleased with the outcome that they posed for a photograph, standing in front of their newly decorated enterprise. Click to see an enlarged version of this image, the Minerd.com "Photo of the Month" in July 2012.

Harbaugh also is known to have painted memorial tablets on the windows of the United Brethren Church in Mill Run or Normalville, signs for the McCormick Drug Co. store in Dunbar, Eicher & Prinkey's mill, the interiors of the Indian Creek Baptist Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church at Normalville and signs in the Pennsville area for the Aaron Furniture House of Connellsville.

|

|

|

Restored Harbaugh sign in Mill Run |

As of 1970, his "I Sell Wagons, Buggies and Goods" sign on the side of Dull's Store (formerly W.S. Colborns's General Store) in Mill Run was still faintly visible. Later, it was restored (seen here) and moved to a nearby restaurant.

~ Journalism and The Guest ~

Uniontown historian Storey writes that there were a "bewildering number" of weekly newspapers in the coal region in the late 1800s which chronicled the stories of the expanding economy. The weeklies were very different from today's newspapers. They were four to eight pages long, and the front pages carried advertising, major national and local news. Reflecting the region's bustling economy, stories focused on coal and coke production, railroad shipments, labor wages and industrial safety. Odd as it might seem, the front pages also carried occasional poems. Inside pages had political and national news, syndicated fiction and display advertisements. Back pages carried local news and gossip from correspondents in outlying towns.

With these newspapers needing new material each week, Harbaugh had plenty of opportunities to publish his work and make his fame with words. As a young man he learned the trade of printing at a Somerset weekly newspaper which today is unknown. For many years, he contributed poems to Uniontown's Genius and was the Mill Run correspondent for Connellsville's Courier, reporting on who was doing what and going where. Among other tactics, he liked to visit nearby counties and pen articles on their local history, economy and personalities.

In 1877, he penned "Up the Youghiogheny" for the Uniontown Genius which narrated an exhausting, nine-day railroad tour in neighboring Somerset County. His description demonstrates his ability to capture the sights of the era:

[W]hile nearing Ursina Junction, the lofty spires of Ursina, glittering in glad sunlight, present an elegant appearance. Arriving at the depot, the handsome town, about 200 feet below road bed, with its numerous dwellings and broad avenues, stretches proudly up the gentle slope beyond the creek, crowned with splendid church edifices and a magnificent school building, speaking a lasting credit, as well as greatly enhancing the appearance of the little mountain city.

|

|

|

Rare view of Ursina, in Harbaugh's time |

The year 1886 brought swings of fortune for Harbaugh, then age 37. His written voice and confidence had grown, he moved into a new house in

Mill Run and was helping his wife with their fourth baby, Annie.

In April of that year, with help from friend I.N. Kooser of Mill Run, he helped found a small monthly newspaper and became its editor, calling it The Guest. It competed directly with an eight-page monthly from nearby Normalville, called The Mountaineer, which was edited by Harbaugh's one-time sign-painting client, storeowner George Campbell. Both were clamoring to gain readership in the Normalville-Mill Run-Ohiopyle corridor, and The Mountaineer later would claim a subscriber base of 1,000.

While the Genius praised his "pronounced success" as an editor and the Courier called The Guest "the brightest of all our smaller papers," Harbaugh's editorship lasted just seven months. In October, he quit to pursue other business. Why he gave up his high profile position is a still a mystery, given his love of being visible.

The rival Mountaineer lasted until at least 1910, though how long The Guest remained in publication is not recorded. (Both papers are mentioned in Nelson's Biographical Dictionary and Historical Reference Book of Fayette County.) Nonetheless, his interest in journalism never waned. Over the years, he penned by-lined articles on economic development, politics and religion. He boasted about his work on The Guest the rest of his life, as reflected in his obituaries in the Pittsburgh and coal region newspapers.

When a successor newspaper was published in Mill Run in 1909-1910, The Advance, he was a contributor, including a poem on the Indian Creek Valley.

|

|

|

Poets of America page |

~ Courting the "Muse of Poetry" ~

In his poetry -- most of which, like his drawings, is lost -- Harbaugh never adopted a standard technique but used a variety of styles to form his rhythms of words and drive home important messages.

In May 1875, the Uniontown Genius published his first known poem, "Emma Belle," and the 60-line work was praised in local newspapers. Later that year the Genius published his second known poem, the 32-line "Six Made Three," an inside-humor piece about three bachelors wooed and won by three maidens.

|

|

|

Book with Al-Ed-Ha poems |

The exact number of poems Harbaugh wrote will never be known. Some appeared in local newspapers, while others were published, distributed and noticed beyond the region. In 1877, Thomas A. Pugh, principal of the Grammar School of Reynoldsburg, Ohio, wrote a letter to the Genius analyzing Harbaugh's poetry: "I am favorably impressed. The narration is most striking -- uniting not only touching candor, but innocence absolutely refreshing..."

Perhaps Harbaugh's greatest literary achievement was in 1890, when he achieved national exposure. His photograph portrait, a short biography and two of his poems were printed in a book entitled Local and National Poets of America. The 1,025-page, three inch thick volume was published by Thomas W. Herringshaw (Chicago: American Publishers Association). It contained "interesting biographical sketches from over 1000 living American poets ... profusely illustrated with over 500 life-like portraits."

Other poets featured are Walt Whitman, Julia Ward Howe, James Whitcomb Riley (the "Hoosier Poet") and Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (father of the Supreme Court Chief Justice). It's possible they might even have read Harbaugh's entry, an intriguing opportunity for new research. Certainly unknown to him was that two other distant cousins had poetry published in the same volume -- Isham "Gaylord" Davidson, an Illinois insurance agent who was married to Allen's distant cousin, Ella Frances (Stillman) Davidson; and S. Isadore Miner, soon to be ex-wife of James Weston Miner of Battle Creek, MI.

|

|

|

Eulogy for a friend's son |

A newspaper article once revealed that when busy with his shoemaking or other pressing responsibilities, Harbaugh had little time to devote to poetry. However, when in the mood, his words would flow. Said the Genius: "He does not believe in machine poetry, but courts the muse until inspired, and then writes with ease and rapidity."

Local residents may not always have appreciated Harbaugh's talent, but there were times of crisis when his skills transcended biases.

In 1890, at the death of three-year-old Roy Colborn, the son of a friend, Harbaugh wrote a moving eulogy which must have touched many souls at the funeral. An excerpt of it read as follows:

|

...Tender

parting thrills our heartstrings |

|

Indian Creek Railroad |

~ Economic and Tourism Development Champion ~

Harbaugh was a constant champion of Fayette County economic development and tourism. He saw too well the county's dependence on just a few large industries, which while providing the blessing of prosperity at times, also provided the curse of crippling economic depression. The unpredictable cycles of coal and coke demand, railroad strikes, and soft farm prices left Fayette Countians vulnerable to forces beyond their control.

To encourage long-term, steady economic health, Harbaugh wrote many articles and poems over the years on the area's attractiveness for tourism as well as a business site. He once penned how the mountain region needed a commerce building to stimulate growth, "where the products of the soil, etc., could be exchanged for cash or other needed articles brought in. Could there be a market established, ready buyers from a distance would soon fill our pockets with solid cash, whereas we cannot find buyers here."

|

|

|

Harbaugh poem, "Ohio Pyle" |

Another time he wrote that "We earnestly invite attention of capitalists and business men generally to the vast fields of Eastern Fayette. We have means of wealth and shipping facilities near; all that is necessary for advancement is the completion of a branch railroad through Indian Creek Valley and for the people to be energetic and watchful, striving for improvement and carefully guarding our interests."

He loved the Indian Creek Valley, which played a small but vital role in the employment and economy of the region, providing natural resources of water, timber, coal, clay, ores and wild game. It also was the location for the Indian Creek Railroad, a spur to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad at the Youghiogheny River. The railroad line is seen here in a rare old postcard photograph.

|

|

|

Ohio Pyle falls, early 1900s |

In a piece on the "fairyland wonders" of the valley, Harbaugh once boasted that "It is not necessary to take a trip to Yellowstone National Park or to Atlantic City to behold beautiful scenery. We have it right here." Just before his death in 1916, he completed a poem on the scenery of the valley which he hoped to have published, but which is now lost.

In Harbaugh's time, the town of Ohiopyle was a magnet for tourists and summertime pleasure-seekers from all over Western Pennsylvania. Featuring spectacular whitewater rapids, falls and parks, and several (now gone) large hotels and railroad stations of the B&O and Western Maryland, the town enjoyed a superb reputation. A rare old postcard of the world-famous falls is seen here, set against the backdrop of the "Little Alps of America."

Harbaugh once wrote that Ohiopyle was "the most stirring and

enterprising place" on the railroad between Connellsville and Cumberland,

and that "all honor is due to the energy of her populace for what she has

attained." One muggy

August, he wrote a poem for the Genius boasting about the town as a cool respite from the heat.

|

Here pleasures and

beauties are scattered around, |

|

|

|

Bathers enjoy a cool swim in Ohiopyle, early 1900s |

~ Political Analyst ~

|

|

|

Political commentary, 1892 |

Voters of Harbaugh's era were much more zealous and demonstrative than today. There was a greater feeling that individuals could make a difference through their vote. During election campaigns, volunteers from both parties held elaborate rallies, lit bonfires and gave passionate speeches to stir up public excitement.

Harbaugh relished political debate and weighed in as a shrewd analyst. He was a Democrat, but found the center to be popular and often called himself an "independent Republican." In 1892, he wrote two pithy poem-songs which the Uniontown Genius said had "been pronounced 'the best things heard in twenty years'." The poems were "Those Good Old Times" and "The Grover Cleveland Wagon." He used the poems to promote Cleveland and his tariff platform, invoke the memory of Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson and attack big business.

Here is an excerpt of "Old Times" to the tune of "Oh Susannah!":

|

Monopolists--"the

favor'd class"-- |

|

CHORUS:-- |

One of his "Wagon" verses sang as follows, to the tune of "Wait for the Wagon.":

|

Her broadsides are

decorated |

|

Indian Creek Baptist Church elders |

~ Baptist Church Leadership ~

Harbaugh led a deeply spiritual Christian life and from a young age was active in the governance and social life of the Indian Creek Baptist Church in Mill Run. (The identities of the individuals standing in front of the building are unknown.)

His faith was partly based on what he called "mystical" experience, and he once stated that he was a "psycho-mental philosopher." This may reflect his embracing in July 1889 of the Christian Science movement, founded in Boston by Mary Baker Eddy. One source describes Christian Science as the belief that humanity and the universe are spiritual rather than material, that truth and good are real and that through prayer and spiritual introspection, God can be known and understood.

At age 21, Allen was baptized at a revival, and at 25 was elected church clerk. He often attended training programs for Sunday School teachers. Reporting on these events, he urged members to be always "seeking out destitute places, gathering in the poor from the highways and the hedges, and instruct them in the way they should go." He also attended annual "camp-meetings" of the county's Evangelical Association and wrote lengthy news articles about their results.

The church played a vital role in the spiritual, educational and social lives of Harbaugh's era. Then, as now, it served as a gathering place for people to share their needs and receive fellowship, inspiration and support. His church continues to flourish today with more than 360 members who worship in a relatively new building dedicated in 1980, with an active and strong outreach program.

|

|

|

Religious commentary, 1898 |

Christmastime was especially important in the life of the Indian Creek church, and Harbaugh gave powerful messages from the pulpit to packed houses. After one such sermon in 1888 -- "Joys of Christmas - Christ Brought Us Life, Light and Divine Grace" -- the congregation broke into a storm of applause. The 2,400-word message was reprinted in the Genius.

In early 1898, having been a subscriber to The Christian Endeavor World for 18 months, he penned an editorial for the publication. It described Christian Science as "that side of Christ's Gospel which the 'new religion' really has grasped and emphasizes." The piece later was reprinted in The Christian Science Journal (April 1898), stating his view that:

Christian Science is Christ's words obeyed practically, even by the spirit of Truth working within us. We believe all you Christian Endeavorers believe, practise what we understand, and have been dong God's work about us. We pray without ceasing and practise the presence of Christ... Having embraced Christian Science in July, 1889, it is "the good part" which shall not be taken away from me. With me it is Life. I have had many demonstrations of the power of Truth over error, and the "good thing" has been eagerly sought for by many patients.

|

|

|

Holiday news coverage |

Since 1865, the Indian Creek church annually has hosted Fourth of July celebrations known as the "Gathering at the Grove." These have included picnic lunches, music, speeches, games, humor and fireworks, along with patriotic salutes of local soldiers and the flag. In his era, starting in mid-morning on the holiday, Harbaugh and others would lead singing and scripture reading, prayer, and recite the Declaration of Independence. After lunch, "all enjoyed sumptuous repast in the cool shade," where the celebration would continue into the late afternoon with singing and speeches.

The celebrations continue today, more than 150 years later, and some of Harbaugh's Minerd-Miner-Minor cousins take part, with emphasis on patriotism, tradition and fellowship.

|

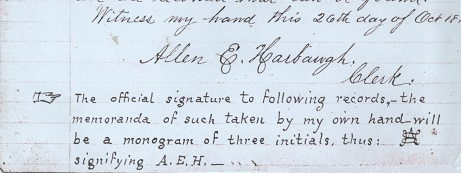

Allen's first entry and monogram as secretary in the Indian Creek Baptist Church minutes ledger, 1874 |

~ A Passion for "Back in the Long Ago" ~

As a boy, Harbaugh knew all four of his grandparents, giving him a strong value for the past, a time he called "back in the long ago." His mind raced as he listened to their stories of pioneer life. His beloved grandmother Martha (Minerd) Imel Harbaugh told him about how as a girl in 1791 she migrated to Fayette County, and her father Jacob Minerd Sr. "pitched his camp under a large tree until he built a cabin... labored rearing a home and clearing land... [and] boiled salt." He also heard how another great-grandfather, Casper Harbaugh, emigrated from Weisbaden, Germany, was a teamster in General Braddock's defeat during the French and Indian War and an eyewitness to Braddock's secret burial near Uniontown.

He held his strong passion for history all his life. In 1883 he was elected to a committee charged with erecting a monument honoring Mill Run's "heroic dead, who served the Union in the war of the rebellion...," though nothing ultimately resulted.

|

|

|

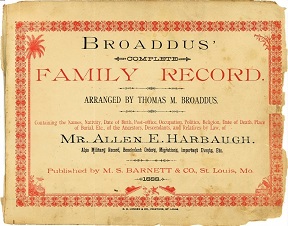

Title page of

Harbaugh's genealogy entries |

Genealogy fascinated him, and he kept personal records in a specially printed record book, Broaddus' Complete Family Record, going back three generations. He logged facts about his and his wife's forbearers such as birthplace, adult residence, occupation, politics, hair and eye color, cause of death, burial site, and dates of birth, marriage and death. His work covered pioneers in his own Harbaugh, Minerd, Eicher, Kern, Cramer and Beeher lines, as well as his wife's people, the Williamses, Galloways and Hannas. View the Broaddus record [PDF, 85.9 MB]

In August 1913, Harbaugh wrote a landmark history of the Minerds and read it aloud at Ohiopyle at the clan's first-ever reunion. (Click to see the first version, written ahead of time, and a second, longer version updated after the fact.) Kinsman George Kern once paid him $5 to help write a history of their mutual ancestor, William Kern, a Revolutionary War soldier and pioneer. This document is believed to have been finished in 1900 and entitled A Chronology of the Eicher and Kern Families from Meager Data and Tradition. In 1914, he wrote a sketch about Normalville settler Samuel Scott.

The influence of his recordkeeping has been felt well beyond his lifetime. In 1935, his records were studied by cousin Charles Arthur Younkin, who was gathering data in connection with the Younkin clan's new national home-coming reunion. The notes opened up new avenues of research on Minerd-Younkin family branches, and were briefly summarized in a letter from Charles to reunion president Otto Roosevelt Younkin on Sept. 29, 1935.

In 1947, 31 years after Harbaugh's death, Harbaugh History, A Directory, Genealogy and Source Book of Family Records, was published. Authors Cora Bell (Harbaugh) Cooprider and J.L. Cooprider of Evansville, Indiana, credit him for having "prepared a family tree of the Casper Harbaugh line, from which much of the early data of this branch was obtained." The Coopriders often were houseguests of Harbaugh's son William on their 1940s research trips to Mill Run.

|

|

|

Memorial for Harbaugh |

~ Mysteries and Missing Works ~

The last 15 years of Harbaugh's personal life were difficult. In 1903, when he was 54, tragedy struck hard. His youngest daughter, the light-haired, blue-eyed Emma, died of typhoid fever. Heartbreak followed twice more in 1913, when his one-year-old grandson died of cholera and the boy's mother died of a series of ailments.

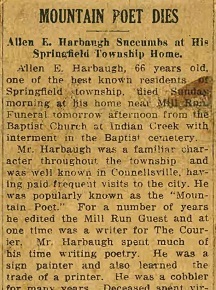

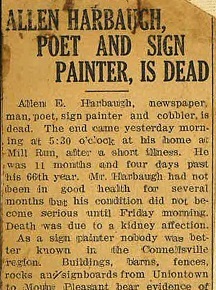

The end for Harbaugh came rapidly and unexpectedly on June 11, 1916, at the age of 66 years, 11 months and four days -- as a victim of infection of the small intestine and kidneys known as "inflammatory enteritis." His official Pennsylvania death certificate listed his occupation as "painter." He was widely eulogized in the newspapers of Pittsburgh, Uniontown, Connellsville and Mill Run, among others. A gold funeral remembrance poster, inscribed with his name, is seen here.

At the time of his death, Harbaugh had just arranged to have a number of his poems published, but the book apparently never made it into print. A profile of his literary career in the Uniontown Peoples Tribune in the 1890s has not been located. How many more of his privately penned poems, eulogies and letters are locked away in private collections or, worse yet lost or destroyed, can never be known.

The Uniontown News Standard published this tribute: "Your works of art, in memory green, How oft we have looked upon the scene, Your pen so many times would cheer, Your body sleeps until resurrection... Your pen inspired stronger faith in God, and sweetly be your seat beneath the sod."

|

| Allen's obituaries, 1916 including the Connellsville Daily Courier (left) Courtesy Rev. Dr. William "Bradford" Harbaugh |

Margaret's obituary, 1921

For as widely as he was known in his lifetime, Harbaugh's fame faded after his death, though he has remained a local legend in his hometown.

Perhaps the greatest twist of fate is that his grave at the Indian Creek Baptist Church was not marked during the lifetimes of his children and many of his grandchildren. For someone whose identity was staked on highly visible work, how ironic it was that Harbaugh and his wife Margaret rested anonymously for decades.

Margaret outlived her husband by five years. Burdened with hardening of the artereries, she suffered a stroke in mid-April 1921 and only lived for another 10 days. Death swept her away on April 16, 1921, at the age of 67 years, eight months and 13 days. Her son Chauncey was the informant for the official death certificate. Funeral services were held in the family church, officiated by Rev. Frank S. Wortman.

Grave marker

installed, 2008

In May 2008, two

of their granddaughters, now with grandchildren and great-grandchildren of their own, led an effort to have a marker installed, with Minerd.com playing a coordinating role at their request. In addition to the precise dates of birth and death for husband and wife, the words "The Mountain Poet, Painter and Artist" were inscribed. The top edge of the granite memorial slopes upward along two angles to meet at a point, symbolizing the mountains Harbaugh loved so much.

~ Epilogue ~

Harbaugh's works live on. He was remembered in the 1930s in a letter written by his cousin's son, Charles Arthur Younkin, to a kinsman, Otto Roosevelt Younkin. (Click to see the entire letter.) Charles and Otto were founding officers of the National Younkin Home-Coming Reunions, held at Kingwood, Somerset County, and they learned that they also shared Harbaugh bloodlines. In the letter, dated Feb. 19, 1935, Charles wrote:

I have found the Harbaughs a tangle pretty much the same as the Younkins... Sure would like to see the book called Harbaugh Stars, which is written in Dutch. Am not just sure if I know who its author is as there were several of the Harbaughs who wrote poems at one time. A.E. Harbaugh of Mill Run was called the Mountain Poet. Many years ago there was one who lived in Indiana, and the Rev. Wm. Henry Harbaugh wrote the Harbaugh Annals, of which I have a copy."

|

Books Featuring Harbaugh's Artwork - 1970 to Present |

|

|

|

|

| History of

Mill Run, 1970 |

Brooks Family History, 1975 | Dunbar, 1983 |

Dunbar: Images of America, 2009 |

|

Calendar with Al-Ed-Ha sign photo |

The 1970 volume, A History of Mill Run, contains a short biography, one of his poems and an informal survey of his works that were still existing in the community.

The Hill Farm sketch was used nearly 100 years later, in 1983, in the book Dunbar: The Furnace Town.

A photograph of one of his billboards for The Famous department store -- seen earlier on this page -- appeared in the 1995 calendar, Yesteryear in Connellsville, published by Marci McGuinness.

|

|

|

Dunbar book, 2004 |

The 1999 "Al-Ed-Ha" feature profile in Western Pennsylvania History has broadened public knowledge about Harbaugh's life and work. The article has been included in the West Virginia University Libraries' "Appalachian Studies Bibliography - 1994-1999" as well as a list of biographies in the eiNetwork (a collaboration of the Allegheny County [PA] Library Association, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh and Commission on the Future of Libraries.

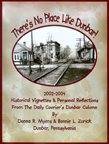

On June 19, 2002, Harbaugh's efforts to sketch the Hill Farm Mine disaster were featured in an article in the Connellsville Daily Courier. The story later was republished in the book, There's No Place Like Dunbar! 2002-2004 - Historical Vignettes and Personal Reflections from The Daily Courier's Dunbar Column, authored by Donna R. Myers and Bonnie L. Zurick of the Dunbar (PA) Historical Society.

When the Dunbar volume was published in 2009 in the "Images of America" series, Harbaugh's sketches of the Hill Farm Mine disaster were reprinted in a chapter entitled "Tragedies." The book's publisher also was the Dunbar Historical Society.

In 2014, material from Allen's Sketch of Minerd Families, Historical and Traditional was published in the fourth edition of In Search of the Turkey Foot Road — Unraveling the Mystery, Charting New History, Plotting the Route, co-authored by Lannie Dietle and Michael McKenzie, edited by Nancy E. Thoerig and produced by the Mount Savage Historical Society in Maryland. [See page 457.]

|

Copyright © 1999, 2000-2006, 2009-2012, 2015-2016, 2024-2025 Mark A. Miner. |

|

Mahoning Mine Man-Way sketch courtesy of Donna and George Myers. Christian Science Journal cover image courtesy of Google Books. |