|

Thomas

G. Minard |

|

| Valley View Cemetery |

Thomas G. Minard was born on May 24, 1835 near Scio, Harrison County, OH, the son of Solomon and Rachel (Little) Minard Sr. He was a Civil War veteran but sadly died young, just a few years after the war, due to the effects of service-related illness.

A friend once commented on how the family name was spelled and pronounced. Carlton T. Baugh of Mt. Vernon, OH "well knew the Minard family" when Thomas was young, "and knows that while the name was spelled 'Minard,' yet most people pronounced it, as if spelled 'Minor,' and this was particularly true in the immediate neighborhood they lived."

Thomas' wife once also noted "the similarity of the sound in the pronunciation of the two names" of Minard and Minor, and made sure hers' was spelled "Minard" in some important papers.

On Christmas Day 1855, at the age of 20, Thomas married 24-year-old Elizabeth Glasner (1831-1895), the daughter of Absalom and Elizabeth (Pierce) Glasner. The ceremony took place at Brown Township, Knox County, OH by the hand of Rev. J.W. Cleaver. On the marriage application, on file today at the Knox County Courthouse, Thomas spelled his last name "Minor."

They together bore a family of five children -- Calvin M. Minarde, Emma Retta Anderson, Louisa Jane "Lucy" Clark, Langford J. Minard and Thomas "Luther" Minard. Thomas' sister Margaret Smale is known to have helped in the delivery of the youngest child in 1868.

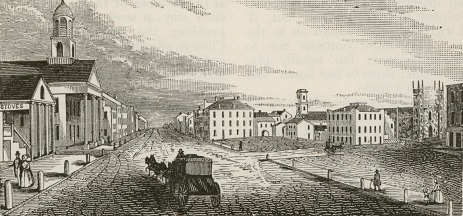

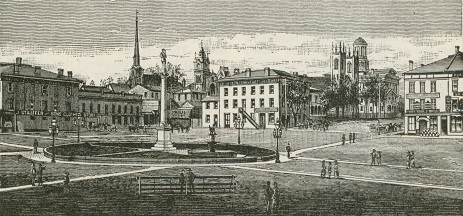

Thomas and Elizabeth made their home near the town of Gambier, Knox County, where Kenyon College today is located. Gambier was just three miles east of the bustling county seat of Mt. Vernon.

|

|

|

Mt. Vernon's public square, near Gambier, 1846 - Historical Collections of Ohio |

As were his father and brothers, Thomas was a carpenter and a "joiner," who knew how to build furniture and houses. Friends said he was "well and strong" as well as "an industrious kind of man." In the years leading up to the war, he was employed in the carpentry shop of Robert Wright in Gambier, Knox County, OH. Co-workers included James E. Rhodes, David Wallison and George Ransom.

When laboring together, Rhodes often complained of feeling weak and dizzy. Colleagues noticed hives breaking out "around his knees, and on his arms at the joints and on his hands," said Rhodes. "This trouble affected him more in hot than cold weather - and caused him when he became very hot to itch & scratch until the skin was right raw. The surface would appear raw & would form with scab."

Ransom said that "I do recall the fact that [Thomas'] hands would crack open in cold weather between his fingers & on their backs."

In 1857, Thomas' father passed away, leaving a widow and a large number of young children. His household goods were sold to raise funds to pay off debts, and Thomas purchased his father's foot axe and hatchet, grindstone as well as other useful items. As well, Thomas was named legal guardian of his 16-year-old brother, Solomon Minard Jr. Thomas may also have provided care for his teenage sister, Elizabeth Shook.

When the Civil War broke out, Thomas enlisted in the 142nd Ohio National Guard, Company F. The enlistment took place on Feb. 6 (or May 2), 1864 at Mt. Vernon, Knox County.

|

| Camp Chase monument |

In May 1864, Thomas became ill while the regiment was camped near Columbus, OH, at Camp Chase. The camp was primarily used as a Confederate prison. In fact, during the war, more than 2,200 Confederates died in the camp, and are buried within its grounds.

Recalled Dr. John J. Scribner, the regiment's physician:

[Thomas] caught cold the night that we stopped at Camp Chase - we were there but

one night, then started on to Washington - The night we were at Camp Chase it

snowed & was then very disagreeable weather. We left Camp Chase about 13 May

& about the 16th we were at Martinsburg W.Va. & while there [his]

sickness assumed form of a fever. We were at Martinsburg about one week - then

went on to Fort Lyon about the 26 May, our Reg. left Fort Lyon I think on June 6

- the soldier left behind ... on account of said fever.

[While at Fort Lyon] I recall the fact that at that time

complicated with soldier's fever was a good deal of trouble in head, he

constantly complaining of his head, kind of dizziness... Soldier also had while

at Fort Lyon ulcers on his legs. I recall this fact because the doctor in charge

ordered me to prepare him a lotion (or wash) for his legs.

Later, Thomas was moved for further treatment to Satterlee General Hospital in West Philadelphia, PA, used as an Army hospital. He is not thought to have ever returned to his regiment for active duty. He was discharged from the Army on Sept. 3, 1864, after having served for 7 months.

Afterward, Thomas returned home. He and Elizabeth moved to College Township, Knox County, about three-fourths of a mile from the village of Gambier. Among their neighbors were Henry C. Wright, William T. Hart, George Ransom and William Aynes. He again worked in Robert Wright's carpentry shop but "was not able to work on out side work, but about all he did was the inside work," a friend said.

|

| History of Knox County, 1881 |

Thomas apparently was a religious man. He is named in the 1881 book, History of Knox County, Ohio, compiled by N.N. Hill, Jr. and published by A.A. Graham & Co. of Mt. Vernon, OH. The text states: "The congregational church at Gambier was first located a little north of the village by the Cumberland Presbyterians. Among the original members were Thomas Minard, Thomas Bennett, John Bennett, and others."

The Minard farm was comprised of a half-acre tract in College Twp., lot no. 28 in the first quarter of Township 6, Range 12, along the road leading from Gambier to Amity.

Perhaps fearing that his days on earth were short, Thomas purchased a policy in the North Western Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee. It was valued at $972.00.

Recalling her husband's physical ailments, Elizabeth said:

My husband was never well after he came from the army & could not do a full days work. He appeared to be kind of stiff across the pit of his stomach -- at times he would be very yellow and again a kind of greenish color. He ... was so stiff and disabled across his stomach that he could not line off his work, as one ordinarily would but would have to get down on his knees to do it. About a year before he died he commenced to complain of one side, ... and soon we noticed ... just between his hip & ribs a little knot about size of a pullets egg. This knot or rising continued to grow until in May before his death. It was tapped & at that time 3 lbs & 9 oz. of fluid was taken from him. It was a wash basin full. From that time this place continued to be a running sore & the flesh all around it became all purple as if dead.

Thomas was treated by Dr. Bowen, and was "tapped" twice. One observer said the fluid "was a thick yellow matter almost like the yolk of an egg." Dr.'s Russell and Stamp of Mt. Vernon also were consulted as needed. Zachariah Carlisle, "who treated sores, wished to treat my husband," Elizabeth recalled, "but Dr. Russell would not permit him."

One day, said George Ransom, while working framing a house:

...he beckoned me to come over to where he was and then asked me to turn a square piece of timber on which he was at work. I said to him, why Tom what is the matter, your a bigger man than me, and ask me to turn the timber for you. Therre upon he pulled up his vest, his coat being off, & showed me a lump in his side.... He said "I am afraid this is about my last work," and I believe it was.

|

| Valley View Cemetery |

On the Fourth of July 1868, Thomas was so sick that he was placed in bed without the ability to get back up. "He just seemed to run down until he was nothing more than skin and bones," his wife said. "The sore was running all this while & would run on the bed." John Bennett, Josiah H. Holmes, William T. Hart, Clay Parker and Franklin G. Beach "all sat up with [him] during his last sickness."

Sadly, on Oct. 3, 1868, within just three years of the war's end, 33-year-old Thomas passed away at Gambier. He died at home, surrounded by family, including his sister and brother in law, Margaret and Samuel Smale, and neighbors Franklin and Sarah Beach.

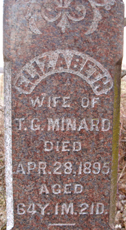

He was laid to rest at Valley View Cemetery (also known as Pleasant Valley Cemetery) near Gambier, at the intersection of Schenck Road and Canada Road. The local preacher inscribed a record of the death in the Minards' Bible, "within a month or six weeks...," Elizabeth recalled. His grave marker is at the highest spot in the cemetery. An inscription at the bottom reads: "Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord."

Records show that payments were made to heirs from his estate later that year. The estate was finally settled on Feb. 9, 1870. In about 1878, when Elizabeth's father died, she served as executor of the estate, and received a portion of its assets.

Among the household items that were left to the family after his death were one cooking stove and furniture, a Bible and other books, two pictures, wearing apparel, three beds, one clock, two tables, one cupboard attached to the house, one bureau, one looking glass, seven chairs, dishes, one family desk, one spade form, two tubs, a lot of crocks and pots, one meat tub, an axe and mattock, one chest and tools, and lumber and sash in his shop.

|

| Arrow points to the Minards' grave |

In paying Thomas' debts, the administrator of the estate reviewed lists from shop keeper William Oliver that included regular purchases of flour, wheat, meat, tobacco, oil, syrup, sugar, corn meal, coffee, rice, pepper and many other goods. The administrator also paid an IOU to Dr. A.B. Hutchinson for such goods as beef, veal, mutton, flour, wheat and a pumpkin. Another debt was owned to Josiah H. Holmes for butter, mutton, corn, dried apples, a cow, timber, straw, a tree and for hauling services. There are other lists of myriad hardware items that Thomas bought on credit that are too numerous to spell out here, but that spell out the minutiae of detail of his last year on earth.

Elizabeth applied for and received a federal pension for her husband's service. In dealing with the government bureaucracy, she had to complete round after round of applications, backed by supporting affidavits from family and friends. Among those relatives who signed their names in support of her pleas were her brother in law Samuel Smale, and son in law Samuel Clark. The pension file today is held by the National Archives in Washington, DC, with a complete copy in our family archives.

Elizabeth was not well-liked by her husband's friends. Carpenter Rhodes said that "Soldier and myself never had an unkind word to pass between us but Mrs. Minard was not a pleasant woman to live by ... [and] we were not on good terms..." In a caustic comment to government officials, former Army surgeon Zachariah Carlisle said, "If poverty and ignorance cuts any figure in a widow's pension claim, her claim is good, very good. She has an abundant supply of both articles."

|

|

|

Mt. Vernon's public square, 1887 - Historical Collections of Ohio, photo by F.S. Crowell |

|

| Valley View Cemetery |

In 1880, "the fall that [President James] Garfield was elected," Elizabeth said, she moved from Gambier to Mt. Vernon, "and have resided here ever since." By 1892, she wrote, she had no means of support and had been "for the last six months supported by public charity."

Her property was located near the "Round House" (as it was known). It was 135 ft. long by 50 ft. wide, with a house and outbuildings on the tract, and sat at the southwest corner of Wilson Avenue and Blue Grass Alley.

Elizabeth wrote her will in Mt. Vernon on or about Nov. 3, 1893. She bequeathed $75 to daughter Emma, $25 to daughter Lucy, and $50 each to sons Langford and Luther, but left nothing to son Calvin, other than his fair share of the residual of the estate once all other debts were paid.

She died less than two years later, on April 28, 1895, at the age of 64 years, one month. She was laid to rest in a casket lined with black cloth, beside her husband at Valley View.

The Minard children must have been close to their unmarried aunt, Rebecca Gleasner. Rebecca died in 1901, and her will directed that her Minard nieces and nephews receive and divide the proceeds of "all her property, real and personal..."

We are grateful to cousin and longtime genealogist, the late Mary Jane (Armstrong) Henney (granddaughter of Samantha "Jennie" [Minard] Armstrong), for providing some of the information in this biography.

Copyright © 2002-2003, 2005, 2007, 2019, 2024 Mark A. Miner |

Sketches of Mt. Vernon from Historical Collections of Ohio (1888) by Henry Howe |