|

|

Friedrich

Meinert Sr. |

|

See: "Immigrant Brothers: Meyndert and Carsten Fredericksen" - "The Immigrants: Jacob and Anna Elisabethe Weber" - and "The Kochertal Party" |

Friedrich Meinert Sr. was born in about 1695 or 1700, likely in or around Albany, NY, and may have been the son of Burger Meynderts and Elsje/Elizabeth Meyer.

Friedrich was united in matrimony with Eva Maria "Mary" Weber ( ? -1776), the daughter of German immigrants Jacob and Anna Elisabethe Weber (or "Weaver"). Her girlhood voyage to America is spelled out in "Eva Maria (Weber) Meinertís Arduous Girlhood Immigration Journey, 1708-1709."

The Meinerts and Webers eventually settled in the Oley Valley near Reading, Berks County, about 52 miles to the northwest of the future nation's capitol of Philadelphia. In fact, by the 1760s, Philadelphia was perhaps the greatest city in the New World and had surpassed all other British North American towns and cities in prosperity and size.

The Meinerts together bore a family of eight children -- Maria "Elizabeth" Gaumer, Jacob Minerd Sr., Borkhard Meinder, Friedrich Meinder Jr., Catharine Eigner, John Meinert, Mary Bohm and Johannes Heinrich Meinert. To read about the influence of the German language and culture they passed along to their children, and many generations of their offspring, click here.)

The family surname became Americanized, and afterward was spelled many different ways -- Meinder, Mynder, Minder, Minerd, Minard, Miner, Minor and Minord. Friedrich's first name became "Frederick," while Eva Maria's name became "Mary." The spellings of the children's last names also varied widely.

|

|

| Friedrich's farm in Oley Township, as seen in 2013. The road at right (Fisher Mill) is the farm's northern boundary, and the intersecting road in the foreground -- Manatawney Road -- marks its eastern border, near the Earl Township line. |

However, their German language continued to be spoken fluently among some of the generations well after the time of the Civil War. In some cases, the language continued to be used until World War I, when German-Americans were heavily persecuted in the United States for fear of their loyalties to the old Fatherland, and even for decades beyond that. One of their great-great-great-great grandsons spoke fragments of German to the founder of this website at a family reunion circa 1992.

Non-Germans in Pennsylvania found the German beliefs, attitudes and activities quite remarkable. Sydney George Fisher (1856-1927), a man of education and high society in Germantown near Philadelphia, observed Germans for decades. In a book he wrote in the 1890s entitled The Making of Pennsylvania, he devoted a chapter to his insights.

(Fisher himself had an indirect connection to our clan. His uncle, Charles Jared Ingersoll, was a congressman from Philadelphian who sold 318 acres of farmland in 1837 to Jacob and Catherine [Younkin] Minerd Jr. in Southwestern Pennsylvania. See more in the Minerd.com page, "Chew and Wilcocks: Influential Early Landowners in Somerset County, PA."

|

"The

Germans" - Observations by Sydney George Fisher in His 1908 Book, The Making of Pennsylvania |

|

|

The great majority of the Germans have lived together in masses, with little or no intermarriage with other elements, and this isolation, combined with their slowness, their opposition to the public school system, and their retaining their language and customs, has checked the advancement of the State... Others, however, have seen, in their thrift, steadiness, and love of liberty, the source not only of all that is great in the State, but of a large part of the greatness of the nation. (p. 71) |

| Besides Holland many of the Pennsylvania Dutch came from the German side of Switzerland. But the great mass of them came from Germany proper,-- from Alsace, Suabia, Saxony, and almost every principality and dukedom of that distracted empire, and most of them from those parts of it called the Palatinate. (p. 89) |

| All classes and sects of the Germans became farmers.... They took better care of their cattle, had better fences, and often built their barns and stables before they built their houses. They were good judges of land, always selected the best, and were very fond of the limestone districts. (pp. 109-110) |

| Most of the Germans hated debt, and were, as a rule, very punctual in their engagements. They worked their farms with their sons, daughters, and wives, and had very few slaves. (p. 111) |

| It is to be feared that many of the Germans too often followed that rule, of selling everything, giving what was left to the pigs, and what the pigs would not eat taking for themselves, by which, it is said, a farmer is sure to grow rich. (p. 111) |

|

|

| The mass of the Germans, especially the sects, were determined from the beginning to keep their own language, literature, and customs, and create a little Germany in the midst of Pennsylvania. In this they have been largely successful. (p. 117) |

| Their maxims and traditions are most conservative, and of high rank among them is that one which instructs a son not to attempt to improve on the ways of his father. (p. 118) |

| They have always had, and still retain, a strong prejudice against education. In colonial times the men are said to have been usually able to read and write, and the women to read, but not to write. (p. 119) |

| Their habit of sequestering themselves on farms, and their division into numerous sects, each one too poor to have good educational means of its own, and too much at variance with the others to unite with them in a general system, tended to intensify the narrowness and isolation of their language. (p. 123) |

| As the Germans kept arriving in increasing numbers, not a little hostility was felt towards them by the English. It was feared that they might come in such swarms as to change the character of the [Pennsylvania] colony, and it was several times suggested that they be permanently disfranchised. (p. 125) |

| Many of the names gradually became anglicized. Bossert becomes Buzzard; Fluck becomes Fluke; Op den Graeff, Updegraff; Conderts, Conrad, Scherker, yerkes; Tissen, Tyson; and Schmidt, plain, honest Smith. In some places the curious phenomenon is seen of a large family, part of whom retain their name in the old German, while the rest are gradually anglicizing it, to the great confusion of the sheriff's jury-list and the tax-assessor. (p. 129) |

Although Frederick may have been an indentured servant, his name has not been found on any such lists, though few have survived to today. It's thought that, if in fact he was an immigrant, that he had to work a few years to accumulate enough capital to buy a farm.

The first known written record of the Meinerts in Pennsylvania is the baptism of daughter Elizabeth by Rev. Joh. Caspar Stoever on Jan. 3, 1731.

|

|

|

Above, arrow points to the precise location of Friedrich Meinert's farm. Below, atlas map of Oley Township, 1876, with a red star marking the site of his farm, southeast of Griesemersville, in the Keifer District. |

|

|

|

|

Daniel Boone |

The old, handwritten survey plat found in Berks County shows that one of the Meinerts' neighbors was George Boone, grandfather of the famous American explorer and pioneer Daniel Boone.

Daniel Boone was born in nearby Exeter Township, Berks County, in November 1734, the same year that Friedrich and Maria settled locally. The Boone family resided on this farm, about 6.5 miles from the Meinerts, until 1750, when they left and migrated southward to North Carolina. The two-story, stone house where Daniel was born, surrounded by a picturesque white picket fence, also is seen here, when photographed for use on a colorized postcard early in the 20th century. Today it is known as the "Daniel Boone Homestead" and is operated by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in partnership with the Friends of the Daniel Boone Homestead.

The Meinerts may also have been neighbors with Abraham Lincoln, grandfather of President Abraham Lincoln. The elder Lincolns resided in an old hillside home and farm in nearby Lorane, Berks County.

The second record of the family is from 1734. That year, on April 10, Frederick had a survey done on a 150-acre farm in Oley. The survey shows that Manatawney Creek flowed through part of his tract. The precise location of the farm is found on Friedrich's ancient patent record, and in Philip E. Pendleton's excellent 1994 volume, Oley Valley Heritage - The Colonial Years.

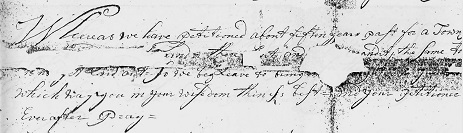

In September 1740, Frederick and other local men signed a petition to have the Oley Valley region recognized as a separate political entity.

In addition to farming, Frederick also was a blacksmith. He may have provided repair and maintenance services for local foundries, such as the Hereford Furnace (with its ruins seen at here), in nearby Hereford Township. The furnace is said to have produced the first cook stove made in America.

|

|

|

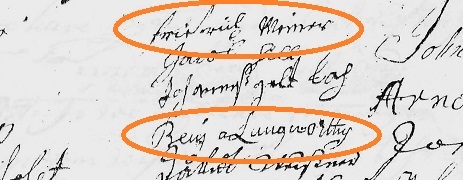

1740 petition signed by Friedrich Meinert and Benjamin Longworthy to create Oley Township |

Frederick died in Oley in 1751, leaving widow Mary and children, including three under age 21. The precise date of his death is not known, nor is his burial place. No obituary was published in the local German language weekly newspaper, the Reading Adler. Papers from his estate show that he paid funds to a Moravian physician who apparently treated him in his last illness. The papers also named "Peter Weaver" as one of the administrators of his estate, presumably a brother in law. Originals of the papers are on file today in the Register of Wills Office in Philadelphia County.

|

|

|

Benjamin's will freeing slave Violet |

His farm was sold to pay his debts and to provide support for the younger children until they reached age 21.

About a year after Frederick's death, widow Mary married their longtime neighbor and Quaker friend, Benjamin Longworthy ( ? -1765). The marriage was controversial, and the "Exeter Meeting officially expelled him from membership for marrying a non-Quaker, ... nonattendance at meeting, and 'disorderly practices'," says Oley Valley Heritage.

The book also says that for years before his marriage to our Mary, Benjamin owned a black slave named Violet, who in turn had two sons and one daughter. Benjamin planned to free the slaves and to give them a financial settlement that would become their "legacy." His intent was to bequeath £50 to Violet as well as "her bed and cloathes, her spining wheel, some flax she hath and some ten household goods that goes in her name...". He also planned to give Mary a small plot within his larger farm, and bequeath the balance of his farm to his nephews Joseph and Moses Roberts, sons of his sister Mary.

|

~ Inventory of Friedrich's Estate, 1752 ~ |

| An inventory was taken of Friedrich's assets at his farm in Oley Township, Philadelphia County on March 14, 1752. Each item was appraised and catalogued in a poorly spelled inventory prepared by Gabriel Boyer and John Jost Yoder. The grand total of the goods was valued at £1755. |

| Ware and apariell | six cowes heffers & one year old Bulls |

| Horse, sadel and bridel | twenty head of Sheep at 5 shillings |

| 2 old guns | two old Horfses |

| 2 puter dishes, 2 plates | weal in Loft and the Rig |

| 3 old buckeds & 1 iron kettle and old bras kettels | Plantation wagin |

| old fryen pan & iron spones, one flesh forke | anvell and hand saw and Dulls Bun Borrers |

| pott and two pott Whracks | a drawnife and sum small Dules and old Iron |

| old pair tongs and shovell and Stillows | Plow and Harrow and Grinestone |

| two Beds, Shetts and wrogs | two old Collers and Traces |

| two spinen whels for flax | abrub how, 2 weedin hows, 2 Dong forkes & hook and one Bell |

| one Bed sheetts, wrogs, pillows | Twenty Gees one shilling |

| one old Bed | Improvements with the winter gran in the Ground |

| old Hekell and one puck skin | 10 Hoggs at 5 shilling |

| 2 old shovells names rings weges old ax |

His health failing, Benjamin wrote his will on Oct. 17, 1765. In the document, he also mentioned "my beloved brother in law and trusty friend Jacob Weaver and my trusty friend Jacob Gellbaugh." Sadly, he died later that month. The details of his passing are lost in the misty haze of time. His burial site is not known.

|

|

|

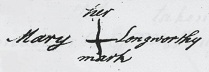

Benjamin's signature, 1765 |

At a hearing in court, Benjamin's nephew Joseph Roberts testified that Benjamin was not of sound mind at the time he made out his will, and said he was under improper influence and had ordered his previously made wills to be burned. Another witness, John Hunter, said that Benjamin's "wife plagued him about his will...." William Boone said that Benjamin had asked him to write out a will for him so he could make his slaves free and

The Oley Valley Heritage book says that Mary allegedly induced him in his "weakened, distraught mind" to re-write his will to give her more favorable terms:

She had talked him out of his longstanding plan to free Violet's children .. and into the making of a new will. Evidently, neither old nor new will freed Violet. The new will retained the inheritance by Longworthy's devout Quaker nephews Moses and Joseph Roberts of the Longworthy farm, while reserving to the widow tenure of the house and its homestead appurtenances. The new will's real bonus for Maria was the right to sell Violet's three children.

|

|

|

Left: ruins of the Hereford iron furnace. Right: Daniel Boone's birthplace. Below: Benjamin Longworthy's sizeable, flat farm next to the Meinerts'. The roadway at left is Covered Bridge Road. |

|

|

|

|

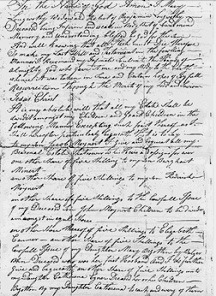

Eva Maria's will, circa 1776 |

The Berks County court ruled that Benjamin's will was not valid.

Mary remained on the farm for a few years, and tax records for the year 1768 show that she was a "wid'o" and owned 70 acres, with two cattle and six sheep. She eventually left the farm for good and moved into the residence of her son Friedrich Meinder Jr. and his wife Catherine (Nein) Meinder. The slaves are thought to have been freed, though their ultimate fates are unknown.

In the year of our nation's independence, Mary died in Oley. Earlier that year, on April 4, 1776, she wrote a will, on file today in Berks County. She wrote that she was "Infirm and weak in Body But of sound mind, Memory and Understanding, blefsed be God for the same, And well knowing that all Flesh must Die Therefore Do make my Last Will and Testament...."

She added that "I Rewmand my Infinite Soul into the Hands of Almighty God who gave it me and my Body to the Earth, whence it was taken in Sure and Certain Hopes of Joyfull Resurrection through the Merits of my Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ." Unable to sign her own name, she made her official mark on the will with an "X." Casper Griesemer and Daniel Hunter witnessed the will.

In the document, she named her children with specific bequests as follow:

It is my absolute will that all my Estate shall be divided amongst my Children and grand Children in the following Manner. Excepting such part thereof as I Shall hereafter particularly bequeath, That is to Say--- to my son Jacob Maynert I give and bequest all my Personal Estate whatsoever to his Heirs and afsigns for ever, one other share of five shillings to my son Frederick Maynert. another share of five shillings to the lawful Ifsue of my Deceased Son John Maynert's Children to be divided amongst in equal shares.--- another Share thereof five Shillings to Elizabeth Caumer --- an other share of five Shillings to the lawful Ifsue of my Daughter Mary Begotten by Balzer Bohn Deceased who was her first Husband and I do further give and bequeath an other share of five Shillings unto my Daughter Catherina Egner Deceased her or her Children. --- Begotten by my Daughter Catherina to each and every of them for ever. I do hereby ordain and appoint my Loving Son --- Burghart Maynert and my Tusty Friend Jacob Roth Joint Executors of this my last will and Testament.

|

Mary's signature |

Her passing thus ended the era of the first generation of the family in America. The burial sites for Frederick and Mary are not known.

Many years after his death, Benjamin Longworthy was mentioned in the 1844 volume, History of the Counties of Berks and Lebanon (Lancaster, PA: G. Hills, Proprietor) and compiled by I. Daniel Rupp, and then again in 1926 in the booklet Annals of the Oley Valley, authored by Rev. Dr. P.C. Croll of Womelsdorf.

Click here to visit the website of the Oley Valley Heritage Association and the Berks County Historical Society.

|

Two publications naming Benjamin Longworthy |

|

~ Other Landmarks in the Oley Valley of Berks County ~ |

|

|

| Manatawny Creek, flowing through the extreme southwest corner of Friedrich Meinert Sr.'s farm in Oley Township |

|

|

| The Yellow House Hotel, built 1801, near the intersection of the Boyertown Pike (Route 562) and Route 662, at the extreme southwest corner of Benjamin Longworthy's old farm. Over the years it has been an inn, repair garage and post office, and today has been restored to a bed and breakfast. |

|

|

|

Old covered bridge crossing the Manatawny stream near the Meinerts' farm |

|

|

| First Moravian church in the valley, erected in 1742, during the Meinerts' lifetimes, and used as a school by the Moravian community between 1742 and 1776. |

|

|

| Oley house built by Dr. George DeBenneville in 1745, said to have been the "cradle of American Universalism" -- a doctrine of theology believing that Hell exists to purify, not punish, and that all souls ultimately will reach salvation. |

|

|

|

Farm of President Lincoln's great-great grandfather, Mordecai Lincoln |

|

Copyright © 2000-2003, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2024-2025 Mark A. Miner and Eugene F. Podraza. The Daniel Boone steel engraving is based on an original painting by Chappel, as published in 1862 by Johnson, Fry & Co., New York |