|

Mahala

(Minor) White |

|

|

|

Mahala and Luther White |

Mahala (Minor) White was born on April 22, 1823 on the family farm at Sego, Perry County, near Zanesville, OH, the daughter of Daniel and Peggy (Fluckey) Minor Sr. With her husband, she was a pioneer settler of Missouri and Kansas, but became a victim of the hardships of pioneer life.

As a 12-year-old, in 1835, Mahala moved with her parents from Perry County to Cardington, Morrow County, OH.

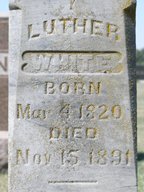

On April 2, 1846, in Cardington, at the age of 23, Mahala married 26-year-old local farmer Luther White (1820-1891). Luther was born near Cardington on March 4, 1820, the son of Noah and Frances (Newton) White.

Their four children were Lester White, Helen Clark, Layton White and Frances Jeanette "Nettie" Bailey. They initially lived on a 50-acre farm at Cardington that once had been owned by her father.

Luther served as a class leader at the local church, the Bethel Methodist Church, circa 1857 and 1864. He is mentioned several times in the booklet, History of Bethel Methodist Church, published in the summer of 1951. (Note -- the church closed in 1969 and later was torn down.)

|

|

|

The old homestead near Cardington where the Whites lived before migrating to Missouri and Kansas |

In 1869, after both of Mahala's parents had died, the Whites decided to venture west with their four children, becoming pioneer settlers of Missouri. The farm was near Haseville, Linn County, MO, about seven miles east of Laredo, Grundy County, MO. Their settlement was, recalled a granddaughter, "near the general store, the Methodist Church and adjoining cemetery." It was likely during this stay that Mahala became a permanent invalid.

|

|

|

Mahala White |

With Mahala's sister and brother in law Lydia and James R. Brown having settled further west, to Medicine Lodge, Barber County, KS, the Whites likely were induced to join them there. The land was exceptionally flat, with farm purchase prices apparently were affordable. They may have felt that the climate might help Mahala's health. Thus, after 15 years of life in Missouri, Mahala and Luther made the decision to move with their adult children to south-central Kansas, 82 miles to the west of Wichita. Only married daughter Helen Clark stayed behind with her husband and children, as their lives already were established in the Haseville and Laredo area.

|

|

|

Luther White |

According to a family manuscript:

In 1884, all of the families, with the exception of Helen, emigrated to Barber County [in] south-central Kansas. After a long and arduous journey by rail to Harper, then by wagon, with their household goods aboard, they reached their destination and homesteaded farms about a mile southeast of the present town of Isabel, located 30 miles northeast of the historic town of Medicine Lodge, Kansas. They were among the first settlers to that sparsely settled territory.

Medicine Lodge, the county seat of Barber County, had just 17 years earlier been the site of landmark peace treaties between the United States Government and the Five Tribes of Plains Indians. Under the treaties' terms, the Native Americans agreed to be relocated to reservations in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Just a few months before the Whites arrived, Medicine Lodge began to take shape as an important trade center, and a company was organized to build what became the Grand Hotel, the tallest building west of Wichita at that time.

Although arrived in her new home in Kansas, Mahala "did not long withstand the rigors of the climate, nor the hardships of pioneer life," said a family book, co-authored by her granddaughters. They most likely spent their initial months living out of a dugout cellar, until such time as cabin or house could be constructed. The extremes of brutally hot summers, penetrating cold winters, steady winds and ever-present dust on the treeless plains would have been overwhelming to the handicapped woman.

|

|

|

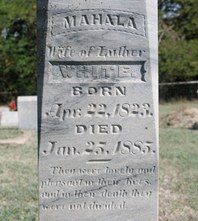

Mahala grave marker in Isabel, 2011 |

In mid-January 1885, as Mahala's life ebbed away, the weather was particularly brutal. The Medicine Lodge Cresset noted that "The recent cold snap has been very severe on range cattle. The rain that came first, freezing as fast as it fell, covered the grass with a sheet of ice, preventing the stock from getting feed, while the snow and wind gradually extinguished what little life there was left. There is no doubt the last storm has made a great many hides."

Mahala died on Jan. 25, 1885 at Isabel, when she was but age 62. She was buried in a small cemetery on the farm of her son Lester, which he set aside presumably for the family but which eventually became the Isabel Cemetery. A moving epitaph, inscribed on her upright grave marker, reads as follows: "They were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in their death they were not divided."

In a terse obituary, the Barber County Index of Medicine Lodge reported: "The wife of David Finley, who lives 14 miles north of the Lodge, died Tuesday.... Old "Mother White" died in the same community January 25, aged 60 years." No death notice is known to have been printed in either the Medicine Lodge Cresset or the Sun City Union.

|

|

|

Barber County Index, 1885 |

After Mahala's passing, her married daughter Nettie Bailey assumed the role of housekeeper in Luther's home. Also residing in the dwelling was her bachelor brother Layton White.

Luther began making payments for his new farm, purchased from the federal government, at the General Land Office at Fort Larned, Kansas, in 1885. The tract he bought comprised 158.8 acres in the northeast quarter of Section 6, Township 30 and Range 11 West. He agreed to pay $1.25 per acre for this land, for a total of $198.50. He fulfilled his payment obligations on Feb. 23, 1889, and received a patent to the acreage, signed by President Grover Cleveland.

With the development of the railroads, Luther was faced with the opportunity to deed part of his farm to the Chicago, Kansas and Western Railroad Company. On Feb. 21, 1887, he conveyed right-of-way ownership to the CK&W of six and 17/100 acres from his farm, located directly west of the town limit of Isabel in Section 6, Township 30, Range 11 West. The railroad paid him $100 for this tract. The following year, in 1888, he sold one acre each to B.F. Coffman and Nancy Roby, along the railroad boundary line. The railroad later was acquired by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

|

|

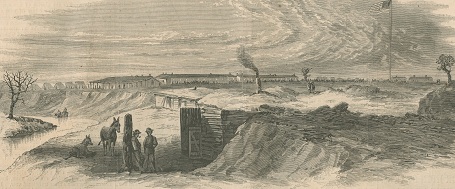

| Fort Larned, Kansas in 1867 -- some 20 years before Luther started making installment payments there for his farm purchase. [Harper's Weekly, June 8, 1867, as sketched by Theodore R. Davis] |

Tragedy rocked the family four-and-a-half years later, on July 8, 1889, when their beloved daughter Nettie tragically was cut down by the Grim Reaper. She was killed by lightning under freak circumstances, adding to the horror. That day, during mid-summer harvest, Nettie and her young children went to visit neighbor William R. and Anna Sellers to help. A hard rain approached from the south just after the noontime dinner. Luther and everyone around him stopped to watch as the torrents came closer, with the children dispatched to the dugout cellar for safekeeping. As the storm hit, the adult women also fled to the cellar, with Luther and the rest of the men taking refuge in the first floor, leaving a door open to watch the rain. When lightning flashed to the south, the men closed the door for fear of another strike.

Five minutes later, when the rain seemed to abate, Nettie ascended from the cellar to investigate. As she reached the cellar door, holding her baby Blanche, a blinding bolt of lightning struck the flue pipe on the roof of the Sellers house. The lightning charge was transmitted down the pipe, through the legs of the iron stove and into the basement, where Nettie was standing. The bolt hit her on the left shoulder and passed through her right foot into the ground. Luther and the others rushed to her aid, and seeing her lifeless, took her outside into the rain to try to revive her. Despite splashing water on her face and shaking her vigorously, it was clear that she was stone cold dead.

Luther was despondent. Several times he appeared to collapse, and sink toward death himself, but his sons managed to keep him alive.

After burying Nettie near the grave of her mother, Luther asked his granddaughter Jennie Gertrude White to assume his household responsibility. Dutifully, said a family story, she "went up the road to her Grandfather Luther White's house to take her place."

|

|

| The Methodist church in Isabel where Luther collapsed and died in 1891 while leading Sunday School singing |

Two years later, in October 1891, Luther's married daughter Helen Clark traveled from Missouri to see him and the rest of the family in Isabel. During the visit, she spoke earnestly with Luther about the possibility of selling off his farm livestock, renting out his farm, and coming back to her home in Laredo, MO, and spending the winter there. He agreed to her proposition, sold the stock, rented the farm and began making preparations to leave in mid-November. In a prescient development, he also wrote his last will and testament on a simple piece of tablet paper on Nov. 5, 1891.

|

|

|

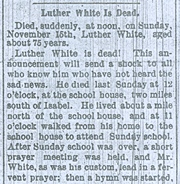

Barber County Index, 1891 |

Just 10 days after completing his last will, on Nov. 15, 1891, the 75-year-old Luther arose as he usually did on a Sunday morning, and walked two miles to the school house where Sunday School was to be held. The shock of what happened next was reported in detail and affection in the Barber County Index newspaper:

After

Sunday school was over, a short prayer meeting was held, and Mr. White, as was

his custom, lead in a fervent prayer; then a hymn was started, he also leading

in the singing. After singing one verse the audience waited for him to start the

second, and as he did not do so, they looked toward him and saw that his head

had fallen forward. His son, Lester, and one or two others hastened to him just

in time to catch his lifeless body as it sank to the floor. The body was taken

to his house, being followed by the entire audience, who were awe-stricken and

filled with grief over the death of one whom they all loved.

...Grand old Luther White. The world can ill afford to spare such

men. He was a land-mark in that section. His word settle all disputes. Nearly

everybody knew him; all knew him by reputation, and all loved him. He was a

Christian soldier and died with the harness on. he had just arisen from his

knees, where he had poured out his soul in prayer for his neighbors, whom he

loved, and, as he supposed, whom he was about to leave for a few months; he was

in the very act of singing praises to his God when his spirit was caught up and

borne away by the angels to the presence of that God whom he loved so well and

whom he had served so long and so faithfully.

...What more could we say were we to write a dozen columns about him. He

lived a Christian life, and by so living earned the right to die a Christian's

death. No earthly honor can for a moment compare with this. We grieve for him as

for any other friend, but we rejoice in the certain knowledge that he is now

happier than he could be here, and that the glories in store for him are beyond

the imaginations of the finite mind.

...Farewell, old friend. The world is better because of your having lived

here. Would that the world could have witnessed your noble death. Like the shock

that is fully ripe, you have been gathered in, and henceforth there is a crown

for thee.

|

|

|

Isabel Cemetery, October 2011 |

|

Luther White's grave |

Family lore is that he died while singing of the well-known hymn "Bringing in the Sheaves." An obituary in the Medicine Lodge Cresset added that he died of heart failure, and that he was laid to rest in "the Bethel cemetery," later to be renamed as the Isabel Cemetery. Carved on the base of his side of their grave marker is this poem: "Our father and mother are gone. They lie beneath the sod. Dear parents tho we miss you much, We know you rest with God."

Son Layton and son in law William Clark were named in Luther's will as the executor of the estate. Under the terms of the will, son Lester was to receive $800, and the other three adult children were to divided the remainder of Luther's personal and real estate. He made special care to state that his late daughter Nettie's two daughters were to receive equal divisions of the assets "as they become of age." Among other expenses, Lester paid out $15.28 for repairs. This included re-plastering and cementing the house and installing a brick flue, lumber for the floor and outhouse. It also involved repairs to the fence and well pump as well as expenditures of $12.00 "for water tank" and $35 for erecting and buying a windmill.

|

|

|

Biography of the Whites |

Some four decades later, in 1931, on a visit to the old Minor homestead in Morrow County, OH, great-grandson Roscoe Conkling Clark and his family visited the Bethel Cemetery near Cardington. There, they viewed the graves of Mahala's parents, Daniel and Peggy Miner. He also photographed the old Luther White homestead, where "the original building was still standing and occupied by a tenant," according to an old family note. "The farm was then owned by Mrs. Myrtle Pringle Kelly…."

Granddaughters Jeannette "Blanche" (Clark) Tarter and Edith (Peterie) Hoyt co-published a landmark history of the family in 1971 along with their cousin, Verda (White) Richey. The thin volume is entitled, Ancestral and Chronological History and Lineage of the Family of Luther White and Mahala (Minor) White, Their Forbears and Descendants, 1665-1971. In the preface to the book, they wrote:

Our forefathers were the pioneers who played such an important part in the founding and establishing of our great country. They were men of courage, brave and fearless, dedicated to God and country, who suffered many hardships and endured many privations. Let us honor and revere their memory.

In 1996, Blanche's elderly son William "Paul" Tarter donated her papers to the Minerd.com Archives.

Some 15 years later, in October 2011, the founder of this website, along with cousin-researcher Eugene Podraza, visited Barber County to research the lives of the White relatives more deeply. Visiting the county courthouse, the Lincoln Library, cemeteries in Isabel and Medicine Lodge, and the old farm tracts, they found a wealth of material. They also were fortunate to meet with several cousins who either live in Medicine Lodge or regularly visit there, and established connections they hope will last for many more years.

|

|

|

Isabel's grain elevator and rail lines, leading directly through Luther and Mahala's farm, out of view at left |

Copyright © 2000, 2009, 2010-2011, 2014, 2018 Mark A. Miner