|

Lydia

(Miner) Brown |

|

Lydia and James R. Brown |

Lydia Ann (Miner) Brown was born on Dec. 7, 1837 in Cardington, Morrow County, OH, the daughter of Daniel and Margaret (Fluckey) Miner Sr. She and her husband, a Civil War veteran, were pioneers of Iowa and Kansas, and were participants in the famed Oklahoma Land Rush.

Lydia married James R. Brown, who served in Company F, 125th Ohio Infantry during the Civil War.

James was born Jan. 28, 1835 at Marion, OH, son of Josiah and Sarah Brown. He stood 5 feet, 8 inches high with blue eyes and dark hair, and taught school before the war.

They were the parents of Harry Brown, Ella Young, Frank Brown, Nellie Jones, Laura Barnum, Gertie Brown, Maggie Brown, Emma Linda McGirk and Bertha Keck.

|

|

|

Lydia Brown |

On Oct. 8, 1862, James enlisted as a sergeant in the 125th Ohio Infantry. Just six days later, when he was age 27, James married our 25-year-old Lydia at Mt. Gilead, Morrow County, before leaving for service. During the duration of the war, she remained behind at their home in Cardington.

Less than a year later, on March 11, 1863, James was honorably discharged from the Army at Louisville, KY. The reason was a disability due to shortness of his right thigh, the result of a broken leg he had suffered prior to enlistment. Nothing more specific about his Civil War service is known.

Of James' health following his tour of Union Army duty, future brother in law Henry Clay Minor wrote the following:

In 1860 & 1861 I was a resident of the town of Cardington, Morrow Co., Ohio. I was well acquainted with J.R. Brown who was also a resident of that town. Mr. Brown as at that time a very fine spessimen of a robust and healthy young man. After my return from the army in Nov. 1864 I again met and was associated with J.R. Brown in business for about 12 months during this time Mr. Brown as in very bad health, was suffering with constipation of bowels, and very frequently unable to attend to any business.

A year or two after the war, the Browns migrated to Iowa, settling in DeSoto, Dallas County (1868) and Montezuma, Poweshiek County (1877). In 1879, they relocated to Kansas, where they ran a dairy in Medicine Lodge, Barber County. "It was a long and arduous journey by rail to Harper, and then by wagon, with all of their household goods abord, until they reached their destination...," said one eyewitness account.

Medicine Lodge was the seat of Barber County, and in 1867 and 1873 was the site of several important treaties with five Native American tribes of the Plains. The town officially was founded in 1873, with a prominent stockade constructed the following year. Thus, the arrival of the Browns in 1879 was to a peaceful, bustling territory with all the promise of a successful future.

|

|

|

Rare postcard view of Kingfisher at the turn of the century |

|

Lydia and Minnie (?) |

In 1884, Lydia and James moved within Barber County a short distance away, to Elm Creek, southwest of Isabel. That same year, they induced Lydia's sister and brother in law, Mahala and Luther White, to come to Kansas from Missouri with their adult children. The Whites arrived in the spring of 1884, but the health of Lydia's sister was fragile. Mahala struggled with the intense heat of summer, added to incessant winds and ever-present rolling dust clouds on a treeless prairie, and then the intense cold of winter. Sadly, in January 1885, after less than a year in Isabel, Lydia's sister died, and was the first burial in what is now the Isabel Cemetery.

Adding to the heartache, that spring, the Browns survived a five-foot flood following a cloudburst in April 1885, but lost 40 head of cattle and their farm was ruined. (Read an eyewitness account of this disaster by daughter Nellie.)

~ The Land Run of 1889 ~

In April 1889, unable to repay their indebtedness, and with Lydia's sister having lain in the grave for the past five years, the Browns made the eventful decision to leave Kansas for the promise of cheap land they could own in Oklahoma Indian Territory. Their aim was to take part in the formal, legal opening of land available for purchase by settlers.

In a memoir, his daughter Laura Barnum wrote:

|

|

|

Pioneers of Kingfisher County |

[He] was a man about 55 years of age, well educated and refined, who had met with reverses in fortune and with his family was seeking a home in the new country. He had with him on this trip his son Frank, 23 years of age, and the daughters, Nellie, 21 and Laura, 16 (Mrs. E. A. Barnum). His wife and two younger children remained in Kansas with a married daughter.

Where they were headed was known as the "Unassigned Lands," two million acres in Central Oklahoma which previously had been set aside as reservations for the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole peoples. While the federal government had a grand but flawed plan to entice Indians into the benefits of land ownership -- theoretically to help them mix better into the white culture -- the Kingfisher section was to be available for non-Indians.

Having left Kansas, their "outfit consisted of two covered wagons which was trailed by a one horse buggy," wrote a grandson. Nellie and here sister Laura rode to Kingfisher in a buggy drawn by a "mule who was gentle," said a Brown family profile in the 1976 book Pioneers of Kingfisher County. Their father and brother Frank would come later.

The sisters arrived just south of where the Kingfisher Cemetery now is, about one mile west of the town. At the time, the county was known as "Fifth County." They lined up at the "jumping off point" alongside many other eager prospectors and families at the starting line at high noon on April 22, 1889. A gunshot sounded, the signal to cross the line and begin making claims.

|

|

|

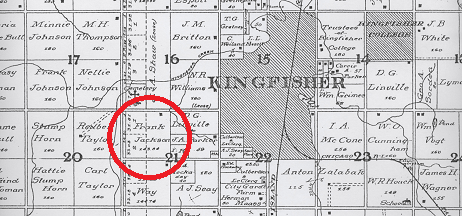

From the 1906 Atlas of Kingfisher County: Nellie's claim -- the northwest quarter of Section 21, circled in red, at that time owned by Frank Jackson. |

|

|

Nellie's mule bolted when the gun fired, "and it was all that the girls could do to hold the mule steady," said the Pioneers book. "Just as soon as they were able to get the mule stopped Nellie sprang to the ground, drove her stake with her name on it into the ground, and proceeded to get a hoe and a wagon sheet from the buggy. She dug up some of the weeds and grass and then spread the wagon sheet on the ground and then just sat down on it. Unbeknownst to Nellie there were 5 or 6 men doing the same thing on this same piece of land, but gallantry prevailed and the men did not contest a woman being on that particular piece of land.

Nellie later wrote a memoir of this nationally historic event -- which she entitled "Great Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889" -- as did her younger sister Laura Barnum -- which she headlined "Run of 1889" -- both published on Minerd.com.

The

family took possession of the property and may have lived in their

wagon for a time until they built some sort of shelter or dugout home. Officially

bearing the description northwest quarter of Section 21, Township 16, Range 7,

the land contained 143 acres, plus lots 1 and 2 of an unspecified property. To

pay for the land, at a price of $1.25 per acre, the family obtained a mortgage

from W.D. Cornelius.

|

|

|

Judge Robert Davis, great-great-grandson of the Browns, stands at the "jumping off point" and gestures toward the direction Nellie Brown and her sister rode in a buggy to make their original claim near Kingfisher, OK. |

On Aug. 12, 1890, Nellie received a receipt from the N.S. Land Office at Kingfisher, signed by J.V. Admire, stating that she had made the last payment of $179.80 and fulfilled her financial obligations in full. A copy of the receipt is preserved today in Kingfisher County Courthouse in Land Office Receipt Book 6, page 3. Four days later, with the land now fully owned by Nellie, and not encumbered in any way, she sold it for $1,000 to her mother. (See Warranty Deed Book 3, page 2.)

The initial farm sat directly along the famed Chisholm Trail, a pathway from Texas to Kansas from 1867 to 1889 on which millions of heads of cattle were rounded up and led to market over the years. It also was in the watershed of the Cimarron River to the north and east.

Despite his financial difficulties in south-central Kansas, James Brown was a shrewd investor and made the most of this opportunity. Within 40 days, on Sept. 26, 1890, he sold or "flipped" the tract for $2,000, or double the amount he had paid for it. (See Warranty Deed Book 3, page 5.) The buyers were Samuel F. Robertson and Clarence L. Gibson, also of Kingfisher. Robertson and Gibson eventually sold the farm to David Gamble and Gibson Morrow.

~ A Second Home at Excelsior ~

|

|

|

Browns at their 2nd farm, Excelsior Twp., Kingfisher Co., 1890s |

Later, in February 1895, the Browns received a Homestead Certificate No. 116 for what became their more or less permanent home. It consisted of a tract of 160 acres in Excelsior Township, Kingfisher County, located to the west of the Indian Meridian line, in the southeast quarter of Section 17, Township 17 North in Range 5 West. The certificate bore the signature of President Grover Cleveland, probably signed by one of his secretaries or deputies of the General Land Office. It sits alongside E0740 Road.

The land was endlessly flat. Winds blew constantly. The ground was covered in a sea of native prairie grass that had been in place for thousands of years and provided a natural feeding ground for wildlife. In his book The Worst Hard Time, author Timothy Egan has written that in the spring in Oklahoma, "the carpet flowered amid the green, and as wind blew, it looked like music on the ground... the world's greatest grassland." Farmers bent on raising wheat and corn had to undertake to plow the thick sod which revealed a rich bed of red soil -- "red dirt." The work would have been back-breaking, even with a good horse and plow.

~ Five Years in San Diego ~

|

|

|

The Browns (left) at their San Diego residence, circa 1901 |

|

|

In 1895, while continuing to own their Oklahoma farm, they moved again to Southern California, establishing a home at Lakeside near San Diego. What drew them there is not known, except that their son Frank was known to have lived there and had obtained stable employment as a cemetery superintendent.

|

|

|

Lydia and James, in older years, San Diego |

They stayed in San Diego for five years. At some point, the Browns had a photographic portrait taken together at Excelsior Studio in San Diego, seen at the very top of this biography.

When the federal census was taken in June 1900, Lydia and James and their daughters Emma (age 21) and Bertha (17) lived together i n San Diego. James' occupation was reported as "farmer." Emma was employed as a sales woman in a grocery.

~ Returning to Central Oklahoma ~

Apparently at some point in 1900, the Browns returned to Oklahoma, returning for good to their Excelsior Township farm, where they remained for most of the rest of their lives, until separated by Lydia's death.

Their frame house stood for many years. The well-constructed building later was sold out of the family, and was still standing in the 1980s, though abandoned. (At the time, the owner decided to tear it down. However, the structure was so strong and solid that it became too much trouble to dismantle. The owner then burned it, with the process taking several days, and dug a hole to bury the remains.)

On Oct.

14, 1912, the Browns celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. They were

photographed together with their family and friends, and apparently had a picnic

lunch in the grove of trees near their home. Among those who

traveled a distance to attend was their nephew, Lester

White, of Isabel, KS.

|

|

|

Above, James and Lydia celebrate their golden wedding anniversary with family and friends in 1912. Below, a picnic thought to have been held the same day. |

|

|

|

Kingfisher Weekly Free Press |

Somehow, despite the many pioneer hardships and endless work endured over the years, they maintained an elegant, handsome appearance, as attested to by their wonderful portraits taken later in life, and seen below.

Continuing to invest in the promise of Oklahoma's future, James in February 1913 acquired four lots from the Land Office at Woodward. These tracts comprised 139.38 acres in lots 1 through 4 in Section 4, Township 28 North in Range 26 West of the Indian Meridien. A few years earlier, in January 1911, his son Frank bought 160 acres from the same Land Office, in the southwest quarter of Section 20, Township Four north of Range 23 East of the Cimarron Maridian.

Suffering with kidney ailments, known at the time as "Bright's Disease," Lydia was treated by Dr. Frank Trigy of nearby Lovell.

Her health sank and she died April 16, 1919, at the age of 82. Death occurred in the home of her married daughter Bertha Keck in Crescent Township. Daughter Nellie Jones, who traveled from her home in Garnett, KS for the funeral, signed the official Oklahoma certificate of death.

|

|

|

Banner Cemetery |

Despite a search made in 2015 by the founder of this website, no newspaper obituaries have been found for Lydia in the at the Kingfisher Public Library's holdings of the Kingfisher Daily Free Press or the Kingfisher Daily Times.

James outlived his wife by four years. He passed away on Oct. 1, 1923, after a trip to California. His obituary was front page news in the Kingfisher Weekly Free Press, which was headlined "Another 89er Passes Away" and noted his age as 88 years, eight months and 28 days.

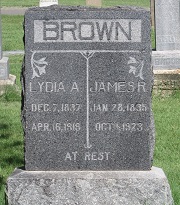

They rest for eternity together at the immaculately groomed Banner Cemetery in Kingfisher. Their grave marker is seen here in a photograph taken in July 2015. A great-grandson has called it one of the finest-kept rural cemeteries in the entire state of Oklahoma.

Granddaughter Alba (McGirk) Kristensen-Peck was a family history buff whose research and neatly typed notes have helped shape our understanding of this branch significantly.

Many

thanks are due to the Browns' great-grandson Keith Barnum who at one time had a website devoted to the Brown-Barnum branch of our family.

The

site was hosted by MyFamily.com.

|

|

|

Above, the Excelsior Twp. farmhouse, ca. 1977, prior to demolition, and the property today, as photographed in July 2015. |

|

|

|

Copyright © 2000-2002, 2010, 2015 Mark A. Miner |

| Many thanks to Norman "Keith" Barnum, Joan (Felder) Geers and Robert E. Davis for sharing their body of research for this page. |