|

Elizabeth

(Houser) |

|

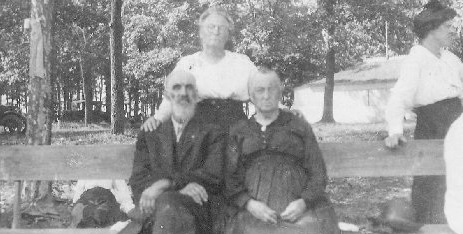

| Elizabeth and William B. Dillow |

Elizabeth W. (Houser) Baker Dillow was born on July 21, 1836 in Fairfield County, OH, the daughter of George W. and Barbara (Miner) Houser.

She and her second husband -- a veteran of the Civil War -- were pioneer settlers of Illinois.

On Feb. 15, 1855, she married her first husband, John Wesley Baker (1831-1861), in Lafayette, Deer Creek Twp., Madison County, OH.

They had two children -- George Wesley Baker and Louisa Baker. Sadly, Louisa died in infancy.

When the 1860 census was taken of Madison County, the Bakers lived in Monroe Township, where John was a farmer. Living next to the family were John and Louisa Baker, ages 60 and 50 respectively, who may well have been John Wesley's parents.

Tragically, after only six years of marriage, John died in Lafayette, at the age of 30, in 1861. The cause is unknown.

|

| Studio photo, DeWitt County |

On March 3, 1863, at Piqua, Miami County, OH, Elizabeth married widower William Baker Dillow (1837-1928). William stood six feet tall, with a dark complexion, dark hair and gray eyes.

William was the son of James and Sarah "Sally" (Baker) Dillow, and was born on March 24 or 25, 1837 in Lafayette, Madison County, OH. Formerly married to Evaline Summers, who died in October 1862, he brought three children to the marriage -- Charles Addison Dillow, James Madison Dillow and Sarah "Etta" Shinneman.

With both of her husbands having Baker family connections, it is likely that they were cousins to each other. In fact, husband #2 had an uncle named "John W. Baker" (1800- ? ).

The Dillows had seven children of their own -- Emma M. Dillow, Susan Clara West, William Watson Dillow, David "Alfred" Dillow, Minnie Elizabeth Wey Emenhiser, Carrie "Livona" Bothwell and Sylvia Delamere West.

On Feb. 13, 1865, William enlisted in the Army during the Civil War. He was assigned to the 32nd OH Volunteer Infantry, Company B. He spent several weeks training at Todd Barracks in Columbus, OH. In March, he came down with the mumps and measles due to "exposure" to the winter weather and "improper care." In his words: "The effect settled in my left side and arm and left shoulder… I also contracted rheumatism and dispepsia from which I have never recovered. This was done in the line of duty. I was treated right in the barracks by the surgeon in charge…" He was discharged on May 11, 1865.

After the war, William suffered from the effects of his wartime illnesses. Wrote Ferguson Rafferty, a friend:

[William] was an able bodied, stout and hearty man. [I] saw said Dillow when he was home on furlough but cannot remember the date, that he was complaining of the effects of mumps and measles. [I] saw him and worked with him for a considerable time after he was discharged from the service and that at that time he complained more or less all the time of suffering from the effects of said mump and measles….

|

| Deland Cemetery |

Elizabeth's sister and brother in law, Mary and Alexander B. McMurray, also resided near Lafayette. Alexander was a trustee of the local township where they lived. They must have migrated to Illinois within a few years of marriage, because in 1868, Elizabeth "united with the Christian church at Long Point, Ill., ... always remaining true to her faith," said a newspaper.

Sometime prior to 1881, the Dillows settled in the town of Weldon near Clinton, DeWitt County.

Tragedy struck the family in May 1883, when teenage daughter Emma was a victim of a senseless household accident, and soonafter died. According to the May 11, 1883 issue of the Clinton Public, Emma:

...was washing some carpet. She built a fire out in the yard to heat the water, and it being a very windy day her dress caught fire, and before the flames could be extinguished her limbs and the lower part of her body were severely burned. It is hardly thought she will recover.

Emma suffered unspeakably for three weeks, and then passed away. Her remains were laid to rest in a cemetery in Deland, IL.

Later in the 1880s, the grief-stricken Dillows moved again, to Iowa, settling in Pocahontas County, where they spent three years. Sometime before 1892, they moved to Munson, Calhoun County, IA, and later returned to Illinois, first to a farm in Gibson City, Ford County, and then to farms in Solomon and Clinton.

|

|

|

The Illinois Central Railroad roundhouse in Clinton |

William purchased two town lots in Clinton in August 1897 from Stephen D. and Minnie J. McBride, for the price of $371. When the federal census was taken in 1900, the Dillows resided in Clintonia Township, DeWitt County. Living in their household was unmarried 28-year-old son David Alfred Dillow and three-year-old granddaughter Mary "Mamie" Baker.

Elizabeth affectionately was called "Grandma Bill" by her grandchildren. She is remembered for scrubbing a ham with soap and water before cooking it.

By 1910, when the census was taken, Elizabeth was living in Arkansas, next to her son Alfred in Kings River, Carroll County. The 1910 census shows that Elizabeth was still raising her granddaughter, 12-year-old Mary Baker, who was residing with her. She apparently returned to Illinois at some point.

|

|

|

William and Elizabeth, seated, and Sarah Etta Shinneman, at a Dillow reunion in Illinois, date unknown. |

In 1925, William wrote this of himself:

I at times is blind. I can't see to read, sometimes I am unable to dress myself a large part of the time. I live with my daughter. She takes care of me.

In 1917, at age 80, Elizabeth suffered a severe attack of gall stones, and she died of exhaustion and shock on Feb. 4 of that year. Her remains were laid to rest near their ill-fated daughter Emma in the Deland Cemetery. The Clinton Daily Public called her "one of the oldest residents of the county." Added another newspaper, "She was a constant sufferer for the last year, always thinking of others, not of herself. She will be missed here, but we are sure mother has gone to that Home where there is no pain, or parting, or sorrow, or cares."

|

| William's military grave marker |

William outlived Elizabeth by 11 years. He suffered many heartbreaks during that span of time.

One such grief-inducing event was in early 1918 when his eldest son Charles, who had been badly hurt three years earlier when caught under a falling tree, finally succumbed to his injuries at the age of 60.

Another occurred in 1920, a murder-suicide involving his 14-year-old granddaughter Evelyn Pearl Dillow and her uncle Raymond O'Neil, some 19 years older. The uncle appears to have suffered from mental health issues and may at one time have been institutionalized. He confided in the elderly William that the two of them had been intimate sexually, but the comment was thought to be fantasy and was ignored. Then on the horrific day of May 17, 1920, the uncle shot and killed Evelyn before shooting himself in the head. William was called to testify at the coroner's inquiry, as described by the Clinton Daily Public: "Feeble and tottering from the weight of 83 years, W.B. Dillow, grandfather of the murdered Evelyn Dillow, in a voice that trembled from his emotions, yesterday gave his testimony before the coroner's jury, telling what he knew of the talk and actions of Raymond O'Neil before O'Neil killed his 14-year-old niece and then turned the gun on himself. That the old grandfather, like many others, thought that O'Neil was queer but "harmless" is evidenced by the fact that when O'Neil told the old man as early as Sunday morning that he had had improper relations with Evelyn, the old man thought it was just the wanderings of an unbalanced mind and did not report it to either the officials nor to the mother of the dead girl."

|

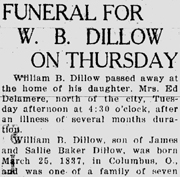

| Obituary, 1928 |

He also endured the untimely deaths of his granddaughter-in-law Caroline "Lena" (Wandschneider) Dillow to peritonitis in 1910 -- granddaughter-in-law Carrie (Rucker) Dillow to tuberculosis in 1913 -- grandson William "Oscar" Dillow in a railroad mishap in 1914 -- grandson-in-law David Johnson in a farm equipment accident in 1920 -- the automobile collision death of granddaughter Caroline Jane (Dillow) Houchins in 1921 followed by her husband Charles in a coal mine equipment failure in 1922. Another grandson-in-law, Tobias Gaddis, shot and killed a man among a group of vigilantes trying to break into his home and administer a "whitecapping" beating in Bloomington, IN in a controversial 1907 case in which he was exonerated.

On April 18, 1928, William died at the home of daughter Sylvia Delamere, north of Clinton. At his death, he left behind 52 grandchildren, 76 great-grandchildren and three great-great grandchildren. He was laid to rest beside his wife Elizabeth and daughter Emma at Deland Cemetery. His named appears on a Civil War monument in Woodlawn Cemetery in Clinton.

Today, there are two markers at the Dillows' grave -- one naming both Elizabeth and William, and the other a standard-issue Civil War veterans marker for William. These monuments were photographed in October 2007 during a research visit by Eugene Podraza and the founder of this website. In about 2002, a great-grandson, great-grandson in-law and a great-great granddaughter formed a new base for Elizabeth and William's stone, and re-set it in the ground.

William's great grandson Mearle "Robert" Dillow (son of Mearle Addison Dillow) published a book entitled Descendants of Thomas and Elizabeth Dillow 1786-1996. An original copy is preserved in the Minerd.com Archives.

Copyright © 2000-2001, 2004-2005, 2007-2008, 2019, 2021 Mark A. Miner