|

James

Minerd Jr. |

James

Minerd Jr. and his twin brother William

were born on Sept. 20,

1840

at Wharton Furnace, Fayette County, PA, the sons of James and Sarah (Walters)

Minerd Sr.

Lynn Point Cemetery

James and two of his brothers served together in the same Civil War regiment, and James was wounded in a

battle in Virginia. The remote, neglected cemetery where

James is buried has been the focus of a cleanup and mapping effort by our reunion officials

and community volunteers.

As a young man, James stood 5 feet, 6 inches tall. He weighed 145 lbs. and had a dark complexion.

Just after his 21st birthday, on Oct. 26, 1861, James married Candace "Candy" Rush (1843-1872), the daughter of John K. and Syvilla (Younkin) Rush of near Farmington, Wharton Township, Fayette County. The wedding was performed by the hand of S.D. Elliott. A notice of the marriage was carried in the Uniontown Genius of Liberty.

(This was one of many marriages between the Minerd and Younkin families in Western Pennsylvania in the 19th century. As well, because Candace was the granddaughter of John J. "Yankee John" Younkin, she was a cousin to some of James's kinfolk -- the family of Henry and Polly [Younkin] Minerd of nearby Kingwood, Somerset County, PA. Click to see typed notes naming Candace's parents in the Yankee John Younkin family line by genealogist Otto Roosevelt Younkin, made in about 1934.)

During the 11 years of their married life together, James and Candace had five children -- James Calvin Minerd Sr., Civillia Minerd (apparently named after her grandmother), Virginia "Jennie" Fisher, Mary F.V. Minerd and Eston Minerd.

With

the Civil War raging, shortly before their 21st birthday, James and William

both

enlisted in the 85th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry,

and were assigned to Company I. (Their 16-year-old brother Isaac

enlisted a month later, and joined them in the company.)

They all served together for three years, and took part in 24 "hard

battles."

![]()

Uniontown Genius of Liberty, 1861

The first few months of military service were spent carrying out "fatigue duty, erecting fortifications, slashing timber [and] picket duty," said Luther S. Dickey's 1915 book, History of the Eighty-Fifth Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. The soldiers trained at Camp LaFayette, "the site of which is now a thickly populated section of Uniontown."

Commanded

by Gen. Joshua Blackwood Howell, the 85th Pennsylvania Infantry was

ordered to march to Virginia, where it took part in a number of key battles in

and around Richmond. As part of the Second Brigade of Maj. Gen. Silas Casey's Division of the Army

of the Potomac, the 85th saw its first major action at the Battle of Seven

Pines/Fair Oaks.

Gen. Howell

In intense fighting near two old farmhouses at Seven Pines on May 30-31, 1862, the regiment "was assigned to the post of honor at the pivotal point of the main line of battle, and maintained that position for three hours, retiring from it only after the entire division was forced back by the overwhelming numbers of the enemy closing in on both flanks," said the History.

In this battle, one of the Minerds' distant cousins, Jacob M. Younkin, of Company B, was killed in action. (Several other distant cousins were members of the 85th regiment -- including James Rowan, Leonard Rowan and John Irving White.)

|

| Battle action at Fair Oaks, "the gallant charge of Casey's Division to save the guns." Painted by Alonzo Chappel, published by Johnson, Fry & Co., New York, 1862 |

The regiment later took part in the Seven Days'

Battle, and then was stationed at various locations in Virginia and North

Carolina. During this time, James and his brothers were constant companions,

bunking and eating together whenever possible.

Aftermath of Fair Oaks battle

At times, James suffered from physical ailments. In the summer of 1862, he broke out in a fever near Richmond. The following summer (of 1863) he came down with kidney disease while on duty near Richmond. While at Bermuda Hundred, VA in 1864, he suffered again from fever.

The regiment was sent in June 1864 to Deep Bottom Landing on the James River near Richmond, VA. A historical marker at the Deep Bottom site says that the landing helped protect a pontoon bridge which allowed Union forces to move back and forth across the James River. On Aug. 13, 1864, the Union Army launched attacks from Deep Bottom aimed at defeating Robert E. Lee's main army at Petersburg, VA, but stiff Confederate resistance foiled the effort. In the History, Dickey wrote: "...the battlefield of Deep Bottom is historic ground. In June, 1864, the Eighty-Fifth accompanied the first expedition of Union troops to occupy this position, and here again a few weeks later, during the month of August, fully one-third of its ranks remaining for duty were killed or wounded."

Painfully for James, he was wounded in action in battle at Deep Bottom the day after the attack began, on Aug. 14, 1864. He was hit by a gunshot in his left leg below the knee. The History describes the battle:

Regiment crossed the James River on pontoon-bridge about 2 a.m. and marched out to within a short distance of the picket line of Foster's brigade, where it went into bivouac, the men lying on their arms in line of battle; shortly after the break of day, before the men had breakfasted, firing began on the picket line in the immediate front, and the Regiment was advanced as if to the support of the pickets; however, before reaching the picket line the Regiment was moved to the left of the position occupied by Foster's Brigade, charged the enemy's works with cheers, carrying his right-pits and driving him into his main works on New Market Heights; during this charge the Regiment lost one officer, and two men killed, and ten men wounded; among the casualties were ... Priv. James Minerd, Company I.

|

|

| Left: rare wartime image of naval transport and monitor vessels on the James River at Deep Bottom. Right: the site today. |

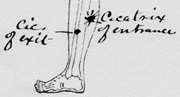

The

wound James received was not serious, but sufficiently crippling. A musket ball passed

through the fleshy part of his calf. It caused so much damage that the muscle

became atrophied and considerably shrunken -- with three abscesses forming

inside within a few months. The scarring on the skin measured 2 x 4 inches. A

sketch made by a physician shows where the bullet entered

and exited James' leg. The sketch is copied from an original in James' Civil War

pension records on file at the National Archives in Washington, DC.

Sketch of James' war wound

James was treated for his wound at Hampton (VA) Hospital, and then at McDougal Hospital in New York. The news of his and other casualties of the regiment were reported in the Sept. 1, 1864 issue of the Uniontown Genius of Liberty.

Just

three months after being wounded, James was discharged, on Nov. 22, 1864. He did

not leave the hospital until late December 1864, when he returned to his wife and family

near Farmington.

News report of James' wound

He immediately was awarded a pension from the federal government as compensation for his wartime wound, at the rate of $4 per month. Over time, the amount was increased to $8 monthly (in 1885) and to $12 (in 1896). The wound did not heal for a year and a half after his discharge, and over time would occasionally break open. An examining physician once said that James "has a dull, heavy pain in his leg, particularly so at night. His leg swells below the wound when he stands on it much."

On May 13, 1868, James and his brother in law Alexander Rush jointly purchased a 50-acre tract of land from Solomon and Anne Workman in Wharton Twp. It was bordered by the farms of E.V. Tissue, Widow Hall, Widow Workman and the Hager family. Another of their nearby neighbors was Pierce Baker.

Tragically, in the winter of 1872, Candace came down with a fatal case of tuberculosis, then known as "consumption." She went to the home of her father in Wharton Twp., where she apparently was cared for by her parents, but without success.

About

that time, on March 15, 1872, Candace and James sold their farm outright to

Alexander Rush. Just 16 days later, on March 31, 1872, Candace passed away at

her father's home. In

a brief obituary, the Uniontown American Standard said:

"She leaves a husband and four children." Her burial site is unknown,

but it is presumed to be in the Farmington area. Her young son James later

wrote, "I was at the burial ... and saw her in the coffin and went to the

semerty and saw her buried." Among those who attended her funeral was

James' brother Isaac.

![]()

Candace death notice, 1872

Widower James was left to raise their young children. It may have been around that time that he moved to nearby Dunbar, Fayette County, PA, which offered jobs in manufacturing and coal mining. His children are thought to have been taken in by other couples. Son James, for instance, was raised by an uncle and aunt, Marcellus and Mary (Rush) Brougher. Daughter Mary was enrolled in the Soldiers Orphans School in Uniontown, where she was living at the time of the 1880 census.

After a dozen years as a widower, James married red-haired Emma Jane "Jennie" Meyers

(1864-1939). The ceremony took place in South

Connellsville (New Haven) on Feb. 24, 1883, and was performed by

Thomas R. Torrance, a justice of the peace. Emma was 24 years younger than her

husband, and had not yet been born when he suffered his Civil War wound at Deep

Bottom.

Lynn Point Cemetery

The Minerds went on to have six children of their own -- John L. Minerd, Stella Minerd, Maud Minerd, Mary Eicher, Albert L. "Bert" Minerd and George Elmer Minerd. Emma's mother Susan Myers helped with the birth of John. Emma brought a son to the marriage -- William Meyers, who was born on Aug. 3, 1881, when she was 17.

Sadly, daughters Mary (1885, age 17), Maud (1891, age one) and Stella (1892, age four) died young, all within a seven-year span. Stella is thought to have choked to death of whooping cough. They all are buried together at the remote, mountainous Lynn Point Cemetery near Dunbar.

The Minerds lived in a little wood-frame house at Tucker Run near Dunbar, where Emma had a garden. She is said to have been a "good sized woman" and a nurse for 35 years and "knew the human body inside out." James suffered from the long term effects of his war wound. A physician once reported that "The leg is weakened and walking causes much stiffness and soreness in it. He is unable to perform certain kinds of labor such as plowing, etc."

James

worked as a coal mine laborer at Dunbar, PA in 1880, at Coalbrook, Fayette

County circa 1899 and at Unity

Twp., Westmoreland County, PA in 1900.

Lynn Point Cemetery

According to oral legend, James often would sit on his wife's lap while friends teased him as they walked past their house, saying, "Jimmy, don't tell me you're still courtin'." James would just smile and reply, "It ain't no time to stop now." Emma later told her granddaughters that James "was the most saintly man she ever met" and that he always had a "twinkle in his eye."

During the Spanish-American War, in 1898-1899, Emma's son William Myers served in the U.S. Army. It is believed he may have been wounded in action and lost part of his leg. Myers returned home after the war, but left the area in about 1906 and did not see his mother again for another 30 years.

In about 1902, James began a slow physical decline. By November 1904, he was admitted to the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Indianapolis, IN. He was treated there for several months and released on Feb. 13, 1904.

James died on May 31, 1909 at their home in Coolspring, Fayette County, at the age of 67. A newspaper reported that "He had lived a devoted Christian life for the past 15 years. Several hours before his death, he called his four children to his bedside and instructed them in the right way of living." He was laid to rest in the family plot at Lynn Point Cemetery near Dunbar.

Emma was devastated by her loss, and wrote that "I was left destitute, no property, no money, no nothing." She soonafter moved to Lemont Furnace, near Uniontown, and by October of that year was living in Vanderbilt, Fayette County.

On April

15, 1912, in Dunbar, 49-year-old Emma married 59-year-old widower Anthony Burns.

He was a Scottish immigrant, and a mine foreman, and the son of Anthony and Mary

Burns. They resided in Vanderbilt. She later wrote, "He abused me so brutal

that I applied for a divorce ... It was granted to me on the 18 day of May

1915."

Obituary, 1909

During the time of Emma's marriage to Anthony Burns, son George was adopted out of the family, in 1915. Emma did not see her son for another 20 years.

By 1916, Emma was again residing with one of her children in Lemont Furnace. On Dec. 23, 1916, Emma married her third husband, Jacob M. Richter. They were divorced on Dec. 2, 1922, and Emma moved into the home of her son Albert in Smithfield, Fayette County. During the time of the Richter marriage, tragedy struck when son John died after a mine accident, the third child Emma had lost.

During World War I, in August 1918, Emma received a telegram from the War Department stating that her son George had been killed instantly in the line of duty in the Navy. This was a terrible mistake, as George is known to have survived the war and lived a long life afterward.

Circa 1924, Emma was residing in Swissvale, near Pittsburgh. In 1929, the House of Representatives approved an increase of her pension to $50 per month. In its report, the government stated that she was suffering from "chronic inflammation of the liver and gall bladder, chronic colitis and rheumatic diathisis, and chronic ovarian disease."

Emma did

not have much of a relationship with her eldest son, William Myers. Writing in

1936, she said, "None of us knows anything of his life for over 30 years.

He only come here on July the 3, 1936. He did not have a trunk or suit case, no

top coat, just one extra shirt & one extra shoe in a zipper & his papers

& one suit of under wear in his shirt sleeves when he landed." She

added, "Correspondence with him while he was away was intermitant, and I at

times did not hear from him for long periods."

Obituary, 1939

Because Emma was drawing a $50/month pension, and Myers was receiving a $75/month pension, Emma convinced him that they should reside together and share expenses. On Aug. 1, 1936, they began the arrangement in Smithfield, but it only lasted a month, ending in a dispute over money. Emma then moved back in with her son Albert in Smithfield.

Emma died in

Pittsburgh on May 4, 1939 at the home of daughter Mary Eicher. She was laid

out at her son Albert's home in Smithfield, and a cousin, Rev. Walter Martin,

preached her funeral service. Emma was buried beside her husband and children at Lynn Point.

A great-great-great

granddaughter at Lynn Point

The Lynn Point Cemetery is all but forgotten today in Fayette County. Teams of cleanup crews, led by National Minerd- Minard- Miner- Minor Reunion officials in 2001, 2002 and 2006 have made major efforts to remove substantial amounts of fallen tree trunks and branches. The cemetery, though uneven in terrain and poorly fenced, has been mapped by a professional engineer.

On June 19, 2002, James was featured in an article in the Connellsville Daily Courier, authored by Donna R. Myers and Bonnie L. Zurick of the Dunbar (PA) Historical Society.

~ Stepson William Meyers ~

Stepson William Meyers claimed to nieces that he was a writer whose work was published in national magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post. He also said he was a newspaper columnist in Washington, DC, but this has not been confirmed.

Circa 1939, he lived in Akron, Summit County, OH. His fate after that is unknown.

| Copyright © 2000-2008 Mark A. Miner |

| Sketch of Gen. Howell and of the Seven Pines battlefield from the History of the Eighty-Fifth Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry by Luther S. Dickey (New York: J.C. & W.E. Powers, 1915). Deep Bottom photograph courtesy of the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress. Sketch of the Battle of Fair Oaks painted by Alonzo Chappel, and published by Johnson, Fry & Co., New York, 1862. |